Conventional memory

This article needs to be updated. (September 2016) |

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (November 2014) |

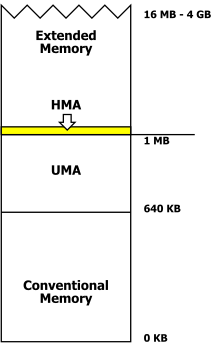

In DOS memory management, conventional memory, also called base memory, is the first 640 kilobytes (640 × 1024 bytes) of the memory on IBM PC or compatible systems. It is the read-write memory directly addressable by the processor for use by the operating system and application programs. As memory prices rapidly declined, this design decision became a limitation in the use of large memory capacities until the introduction of operating systems and processors that made it irrelevant.

640 KB barrier

The 640 KB barrier is an architectural limitation of IBM and IBM PC compatible PCs. The Intel 8088 CPU, used in the original IBM PC, was able to address 1 MB (220 bytes), since the chip offered 20 address lines.

| 0-block | 1st 64 KB | Ordinary user memory to 64 KB (low memory) |

| 1-block | 2nd 64 KB | Ordinary user memory to 128 KB |

| 2-block | 3rd 64 KB | Ordinary user memory to 192 KB |

| 3-block | 4th 64 KB | Ordinary user memory to 256 KB |

| 4-block | 5th 64 KB | Ordinary user memory to 320 KB |

| 5-block | 6th 64 KB | Ordinary user memory to 384 KB |

| 6-block | 7th 64 KB | Ordinary user memory to 448 KB |

| 7-block | 8th 64 KB | Ordinary user memory to 512 KB |

| 8-block | 9th 64 KB | Ordinary user memory to 576 KB |

| 9-block | 10th 64 KB | Ordinary user memory to 640 KB |

| A-block | 11th 64 KB | Extended video memory (EGA) |

| B-block | 12th 64 KB | Standard video memory (MDA/CGA) |

| C-block | 13th 64 KB | ROM expansion (XT, EGA, 3270 PC) |

| D-block | 14th 64 KB | other use (PCjr cartridges, LIM EMS) |

| E-block | 15th 64 KB | other use (PCjr cartridges, LIM EMS) |

| F-block | 16th 64 KB | System ROM-BIOS and ROM-BASIC |

The first memory segment (64 KB) of the conventional memory area is named low memory.

In the design of the PC, the memory below 640 KB was for random-access memory on the motherboard or on expansion boards. The 384 KB above was reserved for system use and optional devices. This upper portion of the 8088 address space was used for the ROM BIOS, additional read-only memory, BIOS extensions for fixed disk drives and video adapters, video adapter memory, and other memory-mapped input and output devices.

The design of the original IBM PC placed the Color Graphics Adapter (CGA) memory map and other hardware in the 384 KB upper memory area (UMA). The need for more RAM grew faster than the needs of hardware to utilize the reserved addresses, which resulted in RAM eventually being mapped into these unused upper areas to utilize all available addressable space. This introduced a reserved "hole" (or several holes) into the set of addresses occupied by hardware that could be used for arbitrary data. Avoiding such a hole was difficult and ugly and not supported by MS-DOS or most programs that could run on it. Later, space between the holes would be used as upper memory blocks (UMBs).

To maintain compatibility with older operating systems and applications, the 640 KB barrier remained part of the PC design even after the 8086/8088 had been replaced with the Intel 286 processor, which could address up to 16 MB of memory in Protected mode. The 1 MB barrier also remained as long as the 286 was running in Real mode, since MS-DOS required Real mode which uses the segment and offset registers in an overlapped manner such that addresses with more than 20 bits are not possible. It is still present in IBM PC compatibles today if they are running in Real mode such as used by MS-DOS. Even the most modern Intel PCs still have the area between 640 and 1024 KB reserved.[3][4] This however is invisible to programs (or even most of the operating system) on newer operating systems (such as Windows, Linux, or Mac OS X) that use virtual memory, because they have no awareness of physical memory addresses at all. Instead they operate within a virtual address space, which is defined independently of available RAM addresses.[5]

Some motherboards feature a "Memory Hole at 15 Megabytes" option required for certain VGA video cards that require exclusive access to one particular megabyte for video memory. Newer video cards on AGP (PCI memory space) bus can have 256MB memory with 1GB aperture size.

3 GB barrier

A similar "3 GB barrier" exists, which limits the addressable RAM to approximately 3 GB under certain conditions, even with e.g. 4 GB RAM installed.

Additional memory

One technique used on early IBM XT computers was to ignore the extended video memory block and push the limit up to the start of the Monochrome Display Adapter (MDA). Sometimes software or a custom address decoder was used so that attempts to use the video card memory went instead to the standard memory. This moved the barrier to 704 KB.[6]

Memory managers on 386-based systems (such as QEMM or MemoryMax in DR-DOS) could achieve the same effect, adding conventional memory at 640 KB and moving the barrier to 704 KB or 736 KB (the start of the CGA). Only CGA could be used in this situation, because Enhanced Graphics Adapter (EGA) video memory was immediately adjacent to the conventional memory area below the 640 KB line; the same memory area could not be used both for the frame buffer of the video card and for transient programs.

The AllCard, an add-on memory management unit for XT-class computers, allowed normal memory to be mapped into the A0000-EFFFF (hex) address range, giving up to 952 KB for DOS programs. Programs such as Lotus 1-2-3, which accessed video memory directly, needed to be patched to handle this memory layout. Therefore, the 640 KB barrier was removed at the cost of hardware compatibility.

It was also possible to use DOS's utility for console redirection, CTTY, to direct output to a dumb terminal or another computer running a terminal emulator. The video card could then be removed completely, and assuming the BIOS still permitted the machine to boot, the system could achieve a total memory of 960 KB of RAM. This also required that the system have at least 2 MB of physical memory in the machine. This procedure was tested on a 486 with IBM PC DOS 7.0.[citation needed] The total operating system footprint was around 20 KB, most of DOS residing in the high memory area (HMA).

DOS driver software and TSRs

Most standard programs written for DOS did not necessarily need 640kb or more of memory. Instead, driver software and utilities referred to as Terminate and Stay Resident (TSR) programs could be used in addition to the standard DOS software. These drivers and utilities typically permanently used some conventional memory, reducing the total available for standard DOS programs.

Some very common DOS drivers and TSRs using conventional memory included:

- ANSI.SYS - support for color text and different text resolutions

- ASPIxDOS.SYS, ASPIDISK.SYS, ASPICD.SYS - all must be loaded for Adaptec SCSI drives and CDROMs to work

- DOSKEY.EXE - permits recall of previously typed DOS commands using up-arrow

- LSL.EXE, E100BODI.EXE (or other network driver), IPXODI.EXE, NETX.EXE - all must be loaded for NetWare file server drive letter access

- MOUSE.EXE - support for mouse device in DOS programs

- MSCDEX.EXE - support for CDROM drive access and drive letter, used in combination with a separate manufacturer-specific driver. Needed in addition to above SCSI drivers for access to a SCSI CDROM device.

- SBCONFIG.EXE - support for Sound Blaster 16 audio device; a differently-named driver was used for various other sound cards, also occupying conventional memory.

- SMARTDRV.EXE - install drive cache to speed up disk reads and writes; although it could allocate several megabytes of memory beyond 640kb for the drive caching, it still needed a small portion of conventional memory to function.

As can be seen above, many of these drivers and TSRs could be considered practically essential to the full-featured operation of the system. But in many cases a choice had to be made by the computer user, to decide whether to be able to run certain standard DOS programs or have all their favorite drivers and TSRs loaded. Loading the entire list shown above is likely either impractical or impossible, if the user also wants to run a standard DOS program as well.

In some cases drivers or TSRs would have to be unloaded from memory to run certain programs, and then reloaded after running the program. For drivers that could not be unloaded, later versions of DOS included a startup menu capability to allow the computer user to select various groups of drivers and TSRs to load before running certain high-memory-usage standard DOS programs.

Upper memory blocks and loading high

As DOS applications grew larger and more complex in the late 1980s, it became common practice to free up conventional memory by moving the device drivers and TSR programs into upper memory blocks (UMBs) in the upper memory area (UMA) at boot, in order to maximize the conventional memory available for applications. This had the advantage of not requiring hardware changes, and preserved application compatibility.

This feature began with DR-DOS 5.0 and was later implemented in MS-DOS 5.0. Most users used the accompanying EMM386 driver provided in DOS 5, but third-party products from companies such as QEMM also proved popular.

At startup, drivers could be loaded high using the "DEVICEHIGH=" directive, while TSRs could be loaded high using the "LOADHIGH", "LH" or "HILOAD" directives. If the operation failed, the driver or TSR would automatically load into the regular conventional memory instead.

CONFIG.SYS, loading ANSI.SYS into UMBs, no EMS support enabled:

DEVICE=C:\DOS\HIMEM.SYS DEVICE=C:\DOS\EMM386.EXE NOEMS DEVICEHIGH=C:\DOS\ANSI.SYS

AUTOEXEC.BAT, loading MOUSE, DOSKEY, and SMARTDRV into UMBs if possible:

LH C:\DOS\MOUSE.EXE LH C:\DOS\DOSKEY.EXE LH C:\DOS\SMARTDRV.EXE

The ability of DOS versions 5.0 and later to move their own system core code into the high memory area (HMA) through the DOS=HIGH command gave another boost to free memory.

Driver/TSR optimization

Hardware expansion boards could use any of the upper memory area for ROM addressing, so the upper memory blocks were of variable size and in different locations for each computer, depending on the hardware installed. Some windows of upper memory could be large and others small. Loading drivers and TSRs high would pick a block and try to fit the program into it, until a block was found where it fit, or it would go into conventional memory.

An unusual aspect of drivers and TSRs, is that they would use different amounts of conventional and/or upper memory, based on the order they were loaded. This could be used to advantage if the programs were repeatedly loaded in different orders, and checking to see how much memory was free after each permutation. For example, if there was a 50 KB UMB and a 10 KB UMB, and programs needing 8 KB and 45 KB were loaded, the 8 KB might go into the 50 KB UMB, preventing the second from loading. Later versions of DOS allowed the use of a specific load address for a driver or TSR, to fit drivers/TSRs more tightly together.

In MS-DOS 6.0, Microsoft introduced memmaker, which automated this process of block matching, matching the functionality third-party memory managers offered. This automatic optimization often still did not provide the same result as doing it by hand, in the sense of providing the greatest free conventional memory.

Also in some cases third-party companies wrote special multi-function drivers that would combine the capabilities of several standard DOS drivers and TSRs into a single very compact program that used just a few kilobytes of memory. For example, the functions of mouse driver, CDROM driver, ANSI support, DOSKEY command recall, and disk caching would all be combined together in one program, consuming just 1 - 2 kilobytes of conventional memory for normal driver/interrupt access, and storing the rest of the multi-function program code in EMS or XMS memory.

DOS extenders

The barrier was only overcome with the arrival of DOS extenders, which allowed DOS applications to run in extended memory, but these were not very widely used outside the computer game area. As games began to use digital sound and digital image textures, they performed better if these large data components could be preloaded into megabytes of memory before playing the game rather than constantly loading the data from external storage.

The first PC operating systems to integrate such technology were Compaq DOS 3.31 (via CEMM) and Windows/386 2.1, both released in 1988. Since the 80286 version of Windows 2.0 (Windows/286), Windows applications did not suffer from the 640 KB barrier. Prior to DOS extenders, if a user installed additional memory and wished to use it under DOS, they would first have to install and configure drivers to support either expanded memory specification (EMS) or extended memory specification (XMS).

EMS was a specification available on all PCs, including the Intel 8086 and Intel 8088 which allowed add-on hardware to page small chunks of memory in and out of the "real mode" addressing space. (0x0400–0xFFFF). This required that a hole in real memory be available, typically (0xE000–0xEFFF). A program would then have to explicitly request the page to be accessed before using it. These memory locations could then be used arbitrarily until replaced by another page. This is very similar to modern virtual memory. However, in a virtual memory system, the operating system handles all paging operations: the programmer, for the most part, does not have to consider this.

XMS provided a basic protocol which allowed the client program to load a custom protected mode kernel. This was available on the Intel 80286 and newer processors. The problem with this approach is that while in 286 protected mode, direct DOS calls could not be made. The workaround was to implement a callback mechanism, requiring a reset of the 286. On the 286, this was a major problem. The Intel 80386, which introduced "Virtual 86 mode", allowed the guest kernel to emulate the 8086 and run the host operating system without having to actually force the processor back into "real mode".

Windows installs its own version of Himem.sys[7] on DOS 3.3 and higher. Windows HIMEM.SYS launches 32-bit protected mode XMS (n).0 services provider for the Windows Virtual Machine Manager, which then provides XMS (n-1).0 services to DOS boxes and the 16-bit Windows machine (e.g. DOS 7 HIMEM.SYS is XMS 3.0 but running 'MEM' command in a Windows 95 DOS Window shows XMS 2.0 information).

The latest DOS extension is DOS Protected Mode Interface (DPMI), a more advanced version of XMS which provided many of the services of a modern kernel, obviating the need to write a custom kernel. It also permitted multiple protected mode clients. This is the standard target environment for the DOS port of the GCC compilers.

There are a number of other common DOS extenders, the most notable of which is the runtime environment for the Watcom compilers, DOS/4GW, which was very common in games for DOS. Such a game would consist of either a DOS/4GW 32-bit kernel, or a stub which loaded a DOS/4GW kernel located in the path or in the same directory and a 32-bit "linear executable". Utilities are available which can strip DOS/4GW out of such a program and allow the user to experiment with any of the several, and perhaps improved, DOS/4GW clones. Another popular API for DOS extenders often used in DOS games was VCPI.

See also

- Expanded memory (EMS)

- Extended memory (XMS)

- High memory area (HMA)

- loadhigh

- Long mode

- Protected mode

- Real mode

- 3 GB barrier

- Unreal mode

- Upper memory area (UMA)

- x86 memory segmentation

References

- ^ Norton, Peter (1986). Inside the IBM PC, Revised and Enlarged, Brady. ISBN 0-89303-583-1, p.108.

- ^ U.S. patent 4,926,322 - Software emulation of bank-switched memory using a virtual DOS monitor and paged memory management, Fig. 1

- ^ Yao, Jiewen; zimmer, Vincent J. (February 2015). "White Paper: A Tour beyond BIOS Memory Map Design in UEFI BIOS" (PDF). Intel Corporation.

- ^ Russinovich, Mark; Solomon, David A.; Ionescu, Alex (2012). Windows Internals. Vol. Part 2 (6th ed.). Microsoft Press. p. 322.

Note the gap in the memory address range from page 9F000 to page 100000...

- ^ Jeffrey Richter. Programming Applications for Microsoft Windows. p. 435 ff.

- ^ [1].

- ^ "Overview of Memory-Management Functionality in MS-DOS". Support.microsoft.com. 2003-05-12. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- Atkinson, C. (unknown date). "What is high memory, why do I care, how do I use it?". Retrieved May 2, 2006.

- http://www.pcguide.com/ref/ram/logicHMA-c.html

- AllCard review, Personal Computer World September 1986, pg 138

This article is based on material taken from the Free On-line Dictionary of Computing prior to 1 November 2008 and incorporated under the "relicensing" terms of the GFDL, version 1.3 or later.