Cosmas Indicopleustes

Cosmas Indicopleustes (Koinē Greek: Κοσμᾶς Ἰνδικοπλεύστης, lit. 'Cosmas who sailed to India'; also known as Cosmas the Monk) was a merchant and later hermit from Alexandria in Egypt.[1] He was a 6th-century traveller who made several voyages to India during the reign of emperor Justinian. His work Christian Topography contained some of the earliest and most famous world maps.[2][3][4] Cosmas was a pupil of the East Syriac Patriarch Aba I and was himself a follower of the Church of the East.[5][6]

Voyage

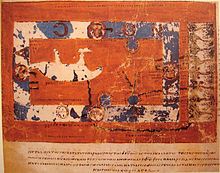

[edit]Around AD 550, while a monk in the retirement of a Sinai cloister,[7] Cosmas wrote the once-copiously illustrated Christian Topography, a work partly based on his personal experiences as a merchant on the Red Sea and Indian Ocean in the early 6th century. His description of India and Ceylon during the 6th century is invaluable to historians. Cosmas seems to have personally visited the Kingdom of Axum in modern day northern Ethiopia, as well as Eritrea. He sailed along the coast of Socotra, but it cannot be ascertained that he really visited India and Ceylon.

Indicopleustes

[edit]"Indicopleustes" means "Indian voyager", from πλέω "(I) sail".[8] While it is known from classical literature, especially the Periplus Maris Erythraei, that there had been trade between the Roman Empire and India from the first century BC onwards, Cosmas's report is one of the few from individuals who had actually made the journey. He described and sketched some of what he saw in his Topography. Some of these have been copied into the existing manuscripts, the oldest dating to the 9th century. In 522 AD, he mentions several ports of trade on the Malabar Coast (South India). He is the first traveller to mention Soriyani Christians in present-day Kerala in India. He wrote:

"Even in Taprobane, an island in Further India, where the Indian sea is, there is a Church of Christians, with clergy and a body of believers, but I know not whether there be any Christians in the parts beyond it. In the country called Malê, where the pepper grows, there is also a church, and at another place called Calliana there is moreover a bishop, who is appointed from Persia. In the island, again, called the Island of Dioscoridês, which is situated in the same Indian sea, and where the inhabitants speak Greek, having been originally colonists sent thither by the Ptolemies who succeeded Alexander the Macedonian, there are clergy who receive their ordination in Persia, and are sent on to the island, and there is also a multitude of Christians. […] The island [of Sri Lanka] has also a church of Persian Christians who have settled there, and a Presbyter who is appointed from Persia, and a Deacon and a complete ecclesiastical ritual. But the natives and their kings are heathens."[9]

Christian Topography

[edit]

A major feature of his Christian Topography is his worldview that the surface of ocean and earth is flat (that is, nonconvex and nonspherical, as perceived by the human senses) and that the heavens form the shape of a box with a curved lid. He was scornful of Ptolemy and others who held that the world's surface was, contrary to human perceptual experience, a spherical shape. Cosmas aimed to prove that pre-Christian geographers had been wrong in asserting that the surface of the earth and surface of the ocean was convex and spherical in shape, and that it was in fact modelled on the tabernacle, the house of worship described to Moses by God during the Jewish Exodus from Egypt. In the centre of the plane is the inhabited earth, surrounded by ocean, beyond which lies the paradise of Adam. The sun revolves round a conical mountain to the north: round the summit in summer, round the base in winter, which accounts for the difference in the length of the day.[7]

However, his idea that the surface of the ocean and earth is nonspherical had been a minority view among educated Western opinion since the 3rd century BC.[10] Cosmas's view was never influential even in religious circles; a near-contemporary Christian, John Philoponus, sought to refute him in his De opificio mundi as did many Christian philosophers of the era.[2]

David C. Lindberg asserts:

Cosmas was not particularly influential in Byzantium, but he is important for us because he has been commonly used to buttress the claim that all (or most) medieval people believed they lived on a flat earth. This claim...is totally false. Cosmas is, in fact, the only medieval European known to have defended a flat earth cosmology, whereas it is safe to assume that all educated Western Europeans (and almost one hundred percent of educated Byzantines), as well as sailors and travelers, believed in the earth's sphericity.[11]

Cosmas was mentioned in Umberto Eco's historical novel, Baudolino. In the book, a Byzantine priest and spy, Zozimas of Chalcedon, refers to his world topography as the key to finding the mythical Prester John:

Well, in the empire of us Romans, centuries ago there lived a great sage, Cosmas Indicopleustes, who traveled to the very confines of the world, and in his Christian Topography demonstrated in irrefutable fashion that the earth truly is in the form of a tabernacle, and that only thus can we explain the most obscure phenomena.[12]

Cosmology aside, Cosmas proves to be an interesting and reliable guide, providing a window into a world that has since disappeared. He happened to be in Adulis on the Red Sea Coast of modern Eritrea at the time (c. AD 525) when the King of Axum was preparing a military expedition to attack the Jewish king Dhu Nuwas in Yemen, who had recently been persecuting Christians. On request of the Axumite king and in preparation for this campaign, he recorded now-vanished inscriptions such as the Monumentum Adulitanum which he mistook for a continuation of another monument detailing Ptolemy III Euergetes's conquests in Asia. Neither have been located by archeologists.[13] Allusions in the Topography suggest that Cosmas was also the author of a larger cosmography, a treatise on the motions of the stars, and commentaries on the Psalms and Canticles.[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Beatrice Nicolini, Penelope-Jane Watson, Makran, Oman, and Zanzibar: Three-terminal Cultural Corridor in the Western Indian Ocean (1799–1856), 2004, BRILL, ISBN 90-04-13780-7.

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008, O.Ed, Cosmas Indicopleustes.

- ^ Yule, Henry (2005). Cathay and the Way Thither. Asian Educational Services. pp. 212–32. ISBN 978-81-206-1966-1.

- ^ Miller, Hugh (1857). The Testimony of the Rocks. Boston: Gould and Lincoln. p. 428.

- ^ Cosmas Indicopleustes (24 June 2010). The Christian Topography of Cosmas, an Egyptian Monk: Translated from the Greek, and Edited with Notes and Introduction. Cambridge University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-108-01295-9. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ Johnson, Scott (November 2012). The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. p. 1019. ISBN 978-0-19-533693-1. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ a b c One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cosmas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 214.

- ^ πλέω. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ J. W. McCrindle, ed. (2010). The Christian Topography of Cosmas, an Egyptian Monk. Cambridge University Press. pp. 118–120, 365. ISBN 9781108012959.

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey B. "The Myth of the Flat Earth". American Scientific Affiliation. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ Lindberg, David "The Beginnings of Western Science, 600 B.C. to A.D. 1450", p. 161

- ^ Eco, Umberto (2002). Baudolino. Orlando, Florida: Harcourt, Inc. p. 215

- ^ Rossini, A. (December 2021). "Iscrizione trionfale di Tolomeo III ad Aduli". Axon. 5 (2): 93–142. doi:10.30687/Axon/2532-6848/2021/02/005.

Further reading

[edit]- Kenneth Willis Clark collection of Greek Manuscripts: Cosmas Indicopleustes, Topographia.

- Cosmas Indicopleustes, ed. John Watson McCrindle (1897). The Christian Topography of Cosmas, an Egyptian Monk. Hakluyt Society. (Reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-108-01295-9)

- Cosmas Indicopleustes, Eric Otto Winstedt (1909). The Christian Topography of Cosmas Indicopleustes. The University Press

- Jeffrey Burton Russell (1997). Inventing the Flat Earth. Praeger Press

- Dr. Jerry H Bentley (2005). Traditions and Encounters. McGraw Hill.

- Schneider, Horst (2011). Kosmas Indikopleustes, Christliche Topographie. Textkritische Analysen. Übersetzung. Kommentar. Turnhout: Brepols.

- Wanda Wolska-Conus. La topographie chrétienne de Cosmas Indicopleustes: théologie et sciences au VIe siècle Vol. 3, Bibliothèque Byzantine. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1962.

- Cosmas Indicopleustes. Cosmas Indicopleustès, Topographie chrétienne. Translated by Wanda Wolska-Conus. 3 vols. Paris: Les Editions du Cerf, 1968–1973.

External links

[edit]- The Christian Topography by Cosmas Indicopleustes

- The Christian Topography by Cosmas Indicopleustes (other site)

- Greek Opera Omnia by Migne Patrologia Graeca with analytical indexes

- Scan of the entire Codex Vat.gr.699 on Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana website

This article uses text taken from the Preface to the Online English translation of the Christian Topography, which is in the public domain.