Cuerda seca

Cuerda seca (Spanish for "dry cord") is a technique used when applying coloured glazes to ceramic surfaces.

When different coloured glazes are applied to a ceramic surface, the glazes have a tendency to run together during the firing process. In the cuerda seca technique, the water-soluble glazes are separated on the surface by thin lines of a greasy substance to prevent them running out of their delineated areas. A dark pigment such as manganese carbonate is usually mixed with the grease to produce a dark line around each coloured area.[1]

In central Asia tiles were manufactured using the cuerda seca technique from the second half of the 14th century.[2] The introduction of different coloured glazes is recorded in the mausoleums of the Shah-i-Zinda necropolis in Samarkand. In the 1360s the colours were restricted to white, turquoise and cobalt blue but by 1386 the palette had been expanded to include yellow, light-green and unglazed red.[3] Large quantities of cuerda seca tiles were produced during the Timurid (1370–1507) and Safavid (1501–1736) periods.[4]

In the 15th century Persian potters from Tabriz introduced the technique into Turkey and were responsible for decorating the Yeşil Mosque in Bursa (1419-1424).[5] Within the Ottoman Empire cuerda seca tilework fell out of fashion in the 1550s and new imperial buildings were decorated with underglaze-painted tiles from Iznik. The last building in Istanbul to include cuerda seca tilework was the Kara Ahmed Pasha Mosque which was designed in 1555 but only completed in 1572.[6][7]

-

Tile from Khargird in Iran, mid 15th century

-

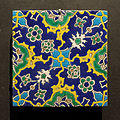

Ottoman tile, Istanbul, first half 16th century

-

Pitcher from Susa in Iran, 8th-9th century

-

Dish from Seville in Spain, early 16th century

Notes

- ^ Campbell 2006.

- ^ Porter 1995, p. 18.

- ^ Atasoy & Raby 1989, p. 373, fn 23.

- ^ Porter 1995, p. 20.

- ^ Atasoy & Raby 1989, p. 83.

- ^ Atasoy & Raby 1989, p. 220.

- ^ Necipoğlu 2005, pp. 377–384.

Sources

- Atasoy, Nurhan; Raby, Julian (1989). Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey. London: Alexandra Press. ISBN 978-1-85669-054-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Campbell, Gordon, ed. (2006). "Cuerda seca and cuenca tiles". The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts, Volume 1. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-19-518948-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Necipoğlu, Gülru (2005). The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-253-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Porter, Venetia (1995). Islamic Tiles. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-1456-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Chapoulie, R.; Delery, C.; Daniel, F.; Vendrell-Saz, M. (2005). "Cuerda seca ceramics from Al-Andalus, Islamic Spain and Portugal (10th−12th centuries AD): Investigation with SEM–EDX and cathodoluminescence". Archaeometry. 47 (3): 519–534. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.2005.00217.x.

- Gestoso y Pérez, José (1899). Ensayo de un diccionario de los artífices que florecieron en Sevilla : desde el siglo XIII al XVIII inclusive. Volume 1 (in Spanish). Seville: En la oficina de la Andalucía moderna. p. 77. OCLC 9986104.

External links

- The cuerda seca method, Qantara project.