Das Käthchen von Heilbronn

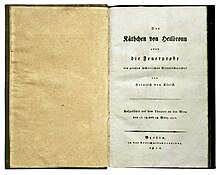

Das Käthchen von Heilbronn oder Die Feuerprobe (Katie of Heilbronn or The Trial by Fire) (1807–1808) is a "great historical knightly play" (German: ein großes historisches Ritterschauspiel) in five acts by the German playwright Heinrich von Kleist. The action of the drama takes place in Swabia during the Middle Ages.

Performances

The play was first performed at the Theater an der Wien on 17 March 1810 and then published in the same year. Originally, the first two acts appeared separately with the play Phöbus, also by Kleist. Although the play has gained respect among modern audiences, it was originally largely rejected. Goethe, who was director of the theatre at Weimar when it was written, refused at first to present it, calling it "a jumble of sense and nonsense."[1] It was also passed over by the Dresdener Hoftheater and the Berliner Schauspielhaus, and in Germany the play was initially only seen in Bamberg's less famous theatre.

List of characters

- The Emperor

- Gebhardt, Archbishop of Worms

- Friedrich Wetter Count von Strahl

- Countess Helena, his mother

- Eleonore, her niece

- Knight Flammberg, the Count's vassal

- Gottschalk, the Count's servant

- Brigitte, Housekeeper in the Count's castle

- Kunigunde von Thurneck

- Rosalie, her chambermaid

- Sybille, Rosalie's stepmother

- Theobald Friedborn, Armorer from Heilbronn

- Käthchen, his daughter

- Gottfried Friedborn, her fiance

- Maximilian, Burgrave of Freiburg

- Georg von Waldstätten, his friend

- Ritter Schauermann, his first vassal

- Ritter Wetzlaf, his second vassal

- The Rheingraf vom Stein, Kunigunde's fiance

- Friedrich von Herrnstadt, Friend of the Rheingraf

- Eginhardt von der Wart, Friend of the Rheingraf

- Graf Otto von der Flühe, Counselor to the Emperor and Judge of the Secret Court

- Wenzel von Nachtheim, Counselor to the Emperor and Judge of the Secret Court

- Hans von Bärenklau, Counselor to the Emperor and Judge of the Secret Court

- Jakob Pech, an innkeeper

- Three gentlemen from Thurneck

- Kunigunde's old aunts

- A boy

- A night watchman

- Numerous knights

- A herald, two coal miners, servants, messengers,pursuers, and people

Synopsis

Act 1 – In an underground cave of the Secret Court (Vehmgericht) lit by a single lamp

The play begins in the secretly convened court in which Count von Strahl is being accused by Theobald, a blacksmith in the town of Heilbronn, of bewitching his young and beautiful daughter Käthchen. In the court they refer to several events in which Käthchen shows an unnatural possession. The first being when Count von Strahl enters his shop and Käthchen bows before him "as if struck by lightning". The second and more daring attempt by Käthchen to follow the Count involves her throwing herself out of a second story window as he leaves. Using almost bully like tactics of interrogation, Käthchen confesses to never having been bewitched. Upon this interrogation of Käthchen, the highly esteemed Count is found not guilty of any action involving Theobald’s daughter and the court dismisses the case entirely.

Act 2 – In a forest near the underground cave of the Secret Court. Later in the mountains near a coal miner's hut. It is night with thunder and lightning

At the beginning of Kleist’s second act Count von Strahl enters into a monologue about his yearning and passionate love for Käthchen. Throughout the monologue it becomes increasingly evident that he will never act upon these feelings, given the vast social class division. We also learn of the Count’s enemy Kunigunde, whose impending lawsuits would take away much of Strahl’s rightful lands. Her former suitor, Maximilian Frederick, however, has kidnapped Kunigunde. Strahl unknowingly defeats her enemy’s capturer and frees Kunigunde. The rules of hospitality at the time require that he invite her back to his castle, whereupon she learns of a dream. The dream indicates that he will find his future bride in the daughter of the emperor. Kunigunde, aware of the information, presents herself as this prophesied woman. Soon after the Count begins to consider making Kunigunde his wife.

Act 3 – Hermitage in a mountainous forest. Later at the Thurneck Castle

Käthchen, in her shame, wants to enter a convent despite her father’s objections. In a last attempt to keep his daughter out of the convent, Theobald suggests that she follow Count von Strahl. The Rhine Graf, now betrayed by Kunigunde, decides to attack Count von Strahl. Through a series of unforeseen events Käthchen intercepts his plans to attack and rushes off to warn Strahl. After his refusal to read the letter, he threatens to whip Käthchen for returning. Eventually Strahl reads the letter and learns of the impending attack. After the fighting has subsided Kunigunde sees an opportunity to get rid of Käthchen and sends her into a burning building to retrieve a picture. Käthchen, with the help of an angel, escapes the building unscathed.

Act 4 – In the mountains, surrounded by waterfalls and a bridge. Later at the Strahl Castle

Strahl pursues the Rhine Graf and Käthchen accompanies them. Käthchen falls asleep beneath an elderberry bush where Strahl questions her. Through questioning they discover that they have met already in their dreams. The Count then begins to realize that Käthchen is his real prophesied wife. Käthchen walks in on Kunigunde during her bathing and is so shocked by what she sees that she cannot speak a word. Kunigunde, having been discovered, decides to have Käthchen poisoned.

Act 5 – City of Worms in a plaza in front of the imperial castle. The throne is to one side. Later in a cavern with a view of the countryside. Finally, the castle square with a view of the castle and a church

Strahl confronts the emperor about the validity of Käthchen’s nobility and in a monologue of the emperor he confesses that he is her biological father. Strahl invites Käthchen to his wedding, but in a twist she learns that it is her wedding. Shocked by this sudden turn of events, Käthchen passes out and the play ends in turmoil.

Author comments

In a letter to Marie v. Kleist (Berlin, Summer 1811), Heinrich v. Kleist wrote: "The judgement of the masses has governed me too much until now; especially Käthchen von Heilbronn bears witness to that. From the beginning, it was a marvellous concept and only the intent to adapt it for stage play has led me to mistakes that I would now like to cry over. In short, I want to soak up the thought that, if a work is only quite freely sprung from one human mind, then that same work must necessarily belong to the whole of mankind."[2]

"Because he who loves Käthchen cannot completely disregard Penthesilea because they belong together like the + and - of algebra, and they are one and the same being, only imagined out of contrary relations."[3] Kleist in a letter to Heinrich J. von Collin (8 December 1808).

"I am now eager to learn what you would have to say about Käthchen, because she is the reverse side of Penthesilea [an Amazon-feminist heroine of an earlier play], her opposite pole, a creature as powerful through submission as Penthesilea is through action ...?"[1][4] Kleist in a letter to Marie von Kleist (late autumn 1807)

Trial by fire

The trial by fire is originally a medieval ordeal meant to test the innocence of a defendant in undecided court cases. There were several types of trials by fire: walking barefoot over hot coals, holding a hot piece of iron in one's hands, or wearing a shirt dipped in hot wax. Whoever managed to survive such an ordeal was considered innocent. Other ordeals were also common, wherein the defendant with hands and feet bound together was thrown into water. Drowning confirmed the defendant's innocence, while staying afloat confirmed the guilty status and the defendant was then put to death. The trial by fire in this text is not referring to an actual ordeal, but simply a test for Käthchen. She passes this test when she returns safely from the burning Thurneck Castle with the help of an angel.[5]

Bibliography

- Alt, Peter-André. "Das pathologische Interesse: Kleists dramatisches Konzept." Kleist: Ein moderner Aufklärer?. 77–100. Göttingen, Germany: Wallstein, 2005.

- Fink, Gonthier-Louis. "Das Käthchen von Heilbronn oder das Weib, wie es seyn sollte: Ein Rittermärchenspiel." Käthchen und seine Schwestern: Frauenfiguren im Drama um 1800. 9–37. Heilbronn, Germany: Stadtbücherei, 2000.

- Horst, Falk. "Kleists Käthchen von Heilbronn – oder hingebende und selbstbezogene Liebe." Wirkendes Wort: Deutsche Sprache und Literatur in Forschung und Lehre 46.2 (1996): 224–245.

- Huff, Steven R. "The Holunder Motif in Kleist's Das Käthchen von Heilbronn and its Nineteenth-Century Context". German Quarterly 64.3 (1991): 304–12.

- Kluge, Gerhard. "Das Käthchen von Heilbronn oder Die verdinglichte Schönheit: Zum Schluss von Kleists Drama." Euphorion, Zeitschrift fur Literaturgeschichte 89.1 (1995): 23–36.

- Knauer, Bettina. "Die umgekehrte Natur: Hysterie und Gotteserfindung in Kleists Käthchen von Heilbronn". Erotik und Sexualität im Werk Heinrich von Kleists. 137–151. Heilbronn, Germany: Kleist-Archiv Sembdner, 2000.

- Kohlhaufl, Michael. "Des Teufels Wirtschaft als Station der Erkenntnis: Ein klassisch-romantischer Topos in Kleists Käthchen von Heilbronn und seine Entwicklung". Resonanzen. 291–300. Würzburg, Germany: Königshausen & Neumann, 2000.

- Linhardt, Marion. "Ziererei und Wahrheit, oder: Das Bühnenspiel der Kunigunde von Thurneck und das erzählte Käthchen von Heilbronn." Prima la danza!. 207–231. Würzburg, Germany: Königshausen & Neumann, 2004.

- Lu, Yixu. "Die Fährnisse der verklärten Liebe: Über Kleists Käthchen von Heilbronn". Heinrich von Kleist und die Aufklärung. 169–185. Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2000.

- Merschmeier, Michael. "Anti-Aging mit Kleist". Theater Heute 8–9.(2004): 87–88.

- Pahl, Katrin. "Forging Feeling: Kleist's Theatrical Theory of Re-Layed Emotionality." MLN 124.3 (2009): 666–682.

- Reeves, W. C. (1991). "False Princess". In Kleist's Aristocratic Heritage and Das Käthen von Heilbronn (pp. 41–59). London: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Schott, Heinz. "Erotik und Sexualität im Mesmerismus: Anmerkungen zum Käthchen von Heilbronn". Erotik und Sexualität im Werk Heinrich von Kleists. 152–174. Heilbronn, Germany: Kleist-Archiv Sembdner, 2000.

- Wagenbaur, Birgit, and Thomas Wagenbaur. "Erotik und Sexualität im Werk Heinrich von Kleists: Internationales Kolloquium des Kleist Archivs Sembdner der Stadt Heilbronn". Weimarer Beiträge, Zeitschrift für Literaturwissenschaft, Ästhetik und Kulturwissenschaften 45.4 (1999): 615–619.

- Weinberg, Manfred. "'... und dich weinen': Natur und Kunst in Heinrich von Kleists Das Käthchen von Heilbronn". Deutsche Vierteljahrsschrift fur Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte 79.4 (2005): 568–601.

- Zimmermann, Hans Dieter. "Der Sinn im Wahn: der Wahnsinn. Das 'große historische Ritterschauspiel' Das Käthchen von Heilbronn". Kleists Erzählungen und Dramen: Neue Studien. 203–213. Würzburg, Germany: Königshausen & Neumann, 2001.

Notes and references

- ^ a b Edith J. R. Isaacs (1920). . In Rines, George Edwin (ed.). Encyclopedia Americana.

- ^ "Das Urteil der Menschen hat mich bisher viel zu sehr beherrscht; besonders das Käthchen von Heilbronn ist voll Spuren davon. Es war von Anfang herein eine ganz treffliche Erfindung, und nur die Absicht, es für die Bühne passend zu machen, hat mich zu Mißgriffen verführt, die ich jetzt beweinen möchte. Kurz, ich will mich von dem Gedanken ganz durchdringen, daß, wenn ein Werk nur recht frei aus dem Schoß eines menschlichen Gemüts hervorgeht, dasselbe auch notwendig darum der ganzen Menschheit angehören müsse."

- ^ "Denn wer das Käthchen liebt, dem kann die Penthesilea nicht ganz unbegreiflich sein, sie gehören ja wie das + und - der Algebra zusammen, und sind ein und dasselbe Wesen, nur unter entgegengesetzten Beziehungen gedacht."

- ^ "Jetzt bin ich nur neugierig, was Sie zu dem Käthchen von Heilbronn sagen werden, denn das ist die Kehrseite der Penthesilea, ihr anderer Pol...?."

- ^ Grathoff, Dirk. "Notes" in Heinrich von Kleist's Das Käthchen von Heilbronn. Reclam, 1992.