Delaware and Hudson Gravity Railroad

| |

| |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Locale | Pennsylvania |

| Dates of operation | 1829–1899 |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 3 in (1,295 mm) |

A predecessor to the Class I Delaware and Hudson Railway, the 1820s-built Delaware and Hudson Canal Company Gravity Railroad ('D&H Gravity Railroad') was a historic gravity railroad incorporated and chartered in 1826 with land grant rights in the US state of Pennsylvania[a] as a humble subsidiary of the Delaware and Hudson Canal and it proved to contain the first trackage of the later organized Delaware and Hudson Railroad (so eventually became a first class Class I Railroad). It began as the second long[b][c] U.S. gravity railroad[d] built initially to haul coal to canal boats, was the second railway chartered in the United States after the Mohawk and Hudson Rail Road[e] before even, the Baltimore and Ohio (e. 1827). As a long gravity railway,[f] only the Summit Hill and Mauch Chunk Railroad (e. 1827) pre-dated its beginning of operations.

Description

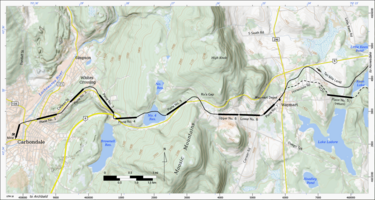

The 4 ft 3 in (1,295 mm) narrow gauge railroad carried coal from Carbondale North-northeast of Scranton over the Moosic Mountains to the D&H Canal in Honesdale. The gravity railroad was opened in 1829,[1] then like most early railways, modified and expanded in stages through 1868. In its final form, the railroad used separate loaded and light tracks. In the gravity railway part, unpowered trains ran by gravity to the bottom of a grade manned by a brakeman operating a muscle powered hand-brake to control speed of descent, to the loading chutes. After being emptied, they were attached to a cable wound on large winch wheels (similar to a ski lift) and hauled up a short, steep inclined planes by a stationary steam engine. The loaded tracks had planes pointing in the direction of Honesdale; the light (return) tracks had planes pointing in the direction of Carbondale.

The gravity railroad operated until 1899, when the canal was abandoned, and was replaced entirely by a new standard 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge line to be used as a conventional steam railroad.[2] Many traces of the tracks remain in the Moosic Mountains. They can still be located on current aerial photographs.

The Delaware and Hudson Canal Gravity Railroad Shops have been demolished, but were once listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[3]

History

Initial Construction

The railroad was originally constructed as a single track from Carbondale to Honesdale. It contained 5 planes ascending 863 feet (263 m) from Carbondale to the summit at Rix's Gap in the Moosic Mountains, and three planes on the 950-foot (290 m) descent to Honesdale where the railroad terminated at the D&H Canal. Each ascending plane was powered by a stationary steam engine which lifted the loaded cars to a "level" which was graded slightly to allow the loaded cars to roll by gravity to the foot of the next plane. In the opposite direction, the empty cars were towed by horses. Each plane contained a single track, with an automatically switched siding in the center where the loaded and empty cars could pass.

The descent of loaded cars between Waymart and Honesdale was interrupted by only a single plane at Prompton, where the track crossed to the north bank of the river and followed its course to Honesdale. From Waymart to Prompton, loaded cars coasted down the "six-mile level" (9.7 km), and after descending the plane at Prompton, were drawn by horses to the Honesdale terminal over the "four-mile level" (6.4 km). The levels were graded so that gravity alone would carry loaded cars on the six-mile level descending at the rate of 44 feet per mile (8.3 m/km), while the four-mile level descended at 26 feet per mile (4.9 m/km) and required horses in both directions, with one horse towing 5 cars.[4]

Much of the railroad was built of trestles constructed from the region's native hemlocks. The rails were 6-by-12-inch (15 cm × 30 cm) hemlock timbers approximately 20 to 30 feet (6.1 to 9.1 m) long, placed on edge. The rails were surfaced with a half-inch thick, two and a half-inch wide (1.3 cm × 6.4 cm) iron strap screwed to the top. After a short time in service, the hemlock was discovered to be too soft, and a 4-inch (10 cm) wide hardwood board was positioned under the iron.[5] On August 8, 1829, the railroad performed a trial of the first steam locomotive in America, the Stourbridge Lion, over the 3-mile (4.8 km) stretch of track from Honesdale to Seelyville, where a low bridge prevented further travel. The shaking timber trestles and rails convinced the officials that the road would not support the use of the locomotive, which was retired and never again used.

Horses drew the loaded cars from the mines to the foot of plane no.1 in Carbondale. In 1836, a short water-powered plane was added to lift loaded cars from the mine to a trestle crossing the river into Carbondale.[6]

1844 Improvements

The road was designed to carry the output of the D&H's mine at Carbondale, transporting 100,000 tons per year (91,000 t) to the canal. In 1844, it was apparent that the road's capacity needed to be increased. The improvements raised the capacity to 500,000 tons per year (450,000 t).[4]

The planes from Carbondale to the summit were realigned to shorten the summit level and increase its grade, and the long Plane No. 6 at Waymart was split into two planes. The road was also double-tracked. The most significant change was the addition of a separate "light track" to return empty cars from Honesdale to Waymart, and the elimination of the plane for loaded cars at Prompton. The light track contained 5 planes, which, except for the first plane at Honesdale, were positioned to take advantage of water power to lift the empty cars on the return trip to Waymart. The track for loaded cars was realigned at Prompton to eliminate the plane there, which allowed the loaded cars to coast under gravity power over a new "ten-mile level" (16 km) from Waymart to Honesdale, which now stayed along the southern bank of the river, descending 44 feet per mile (8.3 m/km) until reaching Honesdale.[4]

The light track originally was carried by a 100-foot (30 m) high trestle across the ravine leading to Cadjaw Pond outside of Honesdale, but in 1848, the trestle was replaced by a horseshoe curve.[7]

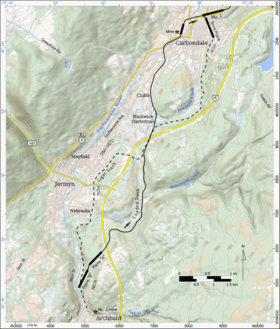

Southern extensions to Archbald and Olyphant

In 1848, the D&H extended the gravity railroad southward from Carbondale to newly opened mines at White Oak Run in Archbald. The extension continued the scheme for light and loaded tracks that had been adopted for the 1844 improvements. The light track commenced with a single "back plane" that lifted empty cars to the light track at Carbondale, where they then rolled under gravity power to the mine at Archbald. The loaded cars were towed from the mine to the foot of two planes at Archbald; after the planes lifted them they coasted to Carbondale.[4]

Ten years later in 1858, additional mines were opened at Olyphant and the road was extended further. The planes on the southern extension were labeled with the letters "A" through "G" in north to south order from Carbondale to Olyphant.[7]

Other important changes were made to the railroad. When originally built in 1829, iron chains were used to move the cars up and down the planes. Frequently the chains broke with catastrophic effect, so blacksmith forges were maintained beside the planes to facilitate repairs. It was soon found that hemp rope performed better than the chains, and all planes were converted to rope. In 1858, the hemp ropes were replaced with wire rope that had been manufactured by the Roebling company. Also during those improvements the strap iron rails were replaced with T rail.[8]

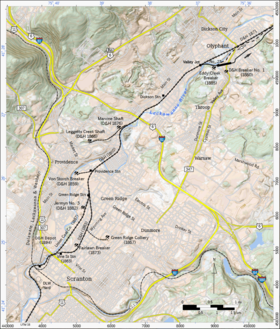

Steam-powered extension to Providence and Scranton

In 1860, the D&H opened new mines in Providence and extended the line to them, a distance of approximately 4 miles (6.4 km). Rather than continuing the gravity line to the mines, the D&H used its first steam locomotives on the new line south of Olyphant, using the 4 ft 3 in (1,295 mm) narrow gauge of the gravity railroad.[7] In 1863, the railroad was extended to the Scranton terminal at Vine Street, where the company built a station and office building. The railroad also started daily passenger service from the Vine Street station to Carbondale.

In 1871, the steam line was extended northward from Valley Junction at Olyphant to Carbondale, where the line connected to the Jefferson Railroad and the Erie Railroad. Portions of this "valley line" had four rails: a common rail, a rail for the 4 ft 3 in (1,295 mm) narrow gauge of the gravity railroad, a rail for 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge, and a rail for the 6 ft (1,829 mm) broad gauge of the Erie.[7]

1868 renovations

In 1866, the D&H purchased the Union Coal Company Railroad which connected with the D&H at Green Ridge. Even though the line was under a 20-year lease to the Lehigh and Susquehanna (which in turn was leased to the Central Railroad of New Jersey) and the D&H could not begin operating the line until 1886, the company nevertheless anticipated increased coal tonnage as a result of its 1866 acquisition, and expanded the gravity road accordingly. After the improvements the line had a capacity of 3,000,000 tons (2,700,000 t) annually, which remained its capacity until its closure in 1899.

Substantial modification was made to the line between Carbondale and Waymart. The five planes which raised loaded cars to the summit at Rix's Gap were replaced by eight planes on a completely new alignment, the separate light track was extended from Waymart to the head of the back plane at Carbondale, and the back plane was eliminated.[7] The water-powered planes on the light track had already been replaced by stationary steam engines, and all planes were being operated by steam.

The new light track contained a 400-foot (120 m) radius hairpin turn at Panther Bluffs which became known as the Shepherd's Crook, later providing extensive views when passenger service between Carbondale and Honesdale was started in 1877.

The planes were re-numbered consecutively starting at Carbondale, following the loaded route to Honedale, then back on the light track to Olyphant, and finally up the loaded track to Carbondale. The gravity line kept that 1868 form for the remainder of its life as a gravity operation. Following the abandonment of the canal in 1898, the gravity line was abandoned and replaced with a 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge steam line, which operated until its abandonment in 1931.

The steam line followed the route of the loaded track between Waymart and Honesdale, and a new alignment from Waymart to Carbondale was built around the foot of Moosic Mountain, looping south to Canaan and rejoining the light line near the head of plane no. 20 at Rix's Gap, where it continued along the light route to Bushwick and Lookout Junction. The hairpin turn at Shepherd's crook was replaced with a switchback.

Passenger service

Although designed for transporting coal to the canal at Honesdale, the line became a popular excursion route when it began passenger operations. Service began as early as 1860 with two small passenger cars running the steam-powered segment between Providence and Valley Junction at Olyphant. By 1868, daily service operated between Carbondale and Providence consisting of 8 passenger and 2 baggage cars. In 1877, passenger service began between Carbondale and Honesdale.[7]

To increase the road's popularity with visitors, the D&H built a 600-acre (240 ha) picnic park at Farview near the highest elevation of the line. A hike up a mountain trail to observation towers at the High Knob peak offered visitors extensive vistas. A connection from the light track to the loaded track was constructed at Bushwick for the convenience of passengers from Honesdale. The passengers cars were met by steam engines at Lookout Junction and brought into Carbondale.

In 1907, the D&H offered the 625 acres (253 ha) it owned at Farview to the state for construction of a state hospital for the criminally insane. The state combined the D&H property with a 468-acre (189 ha) farm and the Fairview facility remains in use to this date as the State Correctional Institution – Waymart. (Although the D&H picnic park was named Farview, the state institutions used the name Fairview.)

Notes

- ^ Excepting the Mohawk and Hudson Railroad chartered also in 1826, and the converted wagon road that went operational in the spring of 1827, the Summit Hill & Mauch Chunk Railroad, all other known and documented non-military built early American Industrial Revolution Railways longer than three miles were comparatively short 'private industrial operations' (i.e. private roads across privately held lands) built by private interests so had no need for land grant charter or right-of-ways beyond permissions of their own management. However, this rule is excepted by both the 1st and 2nd constructed & operational railroads, both of 3 miles (4.8 km)s built for hauling quarried stone to docks at the tidewaters: the 1st chartered & 1st built Leiper Railroad (1810) near Philadelphia, and the Granite Railroad (c. 1826), near Boston, which city, had already had experience seeing two decades of railed roads – the use of temporary portable funicular tramways as it began the decades long process of filling in its Back Bay mudflats. The (eventually) belatedly chartered Mauch Chunk and Summit Hill Railroad (c. 1827) that went operational third was much longer – over 9 miles (14 km) which was eventually both doubled with the advent of its back track (return track) cable railway in 1847, but also enlarged by several miles by its famous switchback zig-zag tracks and two cable inclines up from their various mines in the Panther Creek Valley.

- ^ Placements of a Railway companies founding date such as the first, second, and third rankings among historians devolve into trivial differences between American entities over quibble-some facts, not always easy to document, such as construction start and completion dates. Incorporation dates often depended upon receiving a charter, which depended upon some company applying for rights which in some cases required a formed corporation, or only a formal letter of intentions one would be formed (which might be provisional on the legislation!) and often could expire or incorporate later provisional to obtaining starter-financing – in short 'a which comes first' decision is often a conundrum of causality.

Is the railroad part of a company, and if so, did it obtain a charter then incorporate, or incorporate then apply to a legislative body for land grant rights? Was it a private railroad built solely on private lands, so did not require charters beyond the corporations (e.g. the SH&MC gravity coal railroad built by the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company according to the book, the Delaware and Lehigh Canals had no charter but became the unquestioned second operational common carrier railroad over three miles length.)

The Commonwealth Chartered Granite Railroad in Quincy, Massachusetts, was the first chartered in the 1820s, and completed and to operate, but the first chartered, built and operated was the humble Leiper Railroad that was born in 1810 from the desire to have a canal—and received a charter accidentally, as something of a consolation prize. Several small mining railroads also 'scored' before the SH&MC was built in 1827 by the LC&N.) When did construction begin? Did finances lag and retard completion? When (finally?!) did it begin operations? In point of fact, from 1826 onward – railroads popped up as suggested solutions just about everywhere for a country now sensitized to the need to develop transportation infrastructures. These entities often had only a nominal existence (on paper) for several years whilst their supporters tried to raise funds, or were sham power plays where some speculators secured the right-of-ways to a region, holding it as a resource for latter sale. In short, such rankings are something of a complicated quagmire—no matter how you rank them, you are likely to be wrong in some way. - ^ Nonetheless, several things stand out for railroads which survived beyond a company's first decade: Three railways were chartered in different polities in 1836, the Granite Railroad, the Mohawk and Hudson Railroad and the Delaware & Hudson Gravity Railroad, which may well have inspired the other two given the founding of the parent company in 1823 and the small relative population of investors that early in the country history.

- ^ The D&HGRR was definitely conceived of first, and may have inspired the Summit Hill and Mauch Chunk Railroad, but Josiah White had carefully surveyed and laid out the SH&MC as a wagon road with a near constant grade and once the board authorized the project in 1827, it took only a few weeks for Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company to lay iron capped wooden tracks down the well engineered wagon road bed (finished in 1818) and begin operations as the 2nd operating railroad.

- ^ The Mohawk and Hudson Rail Road was built to cut across a loop (shorten a long stretch) along the Erie Canal.

- ^ The Summit Hill and Mauch Chunk Railroad, like the B&O did not start with steam power, nor initially have cable railway capabilities. It began as a gravity railroad with Mule drawn wagon trains dragging coal cars up the 9 miles back trip to Summit Hill. Its cable winches, stationary engines, and back track were not added until LC&N had engineered the Ashley Planes after establishing the first U.S. wire rope factory in America.

Footnotes

- ^ Shaughnessy 1997, p. 6

- ^ Old Colony Trust Company (1913). Analyses of the Railroad Corporations Whose Bonds are a Legal Investment for Massachusetts Savings Banks, p. 243. Priv. print.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Archbald, James (1847). "Report to John Wurts, President of the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company". American Railroad Journal. 20: 375–376.

- ^ The Delaware and Hudson Company 1925, p. 55

- ^ The Delaware and Hudson Company 1925, p. 101

- ^ a b c d e f Best, G. M. (1951). "The Gravity Railroad of the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company". Bulletin of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society (82): 7–22.

- ^ The Delaware and Hudson Company 1925, p. 155

References

- The Delaware and Hudson Company (1925). A Century of Progress, History of the Delaware and Hudson Company, 1823–1923. Albany, NY: J. B. Lyon Company. OCLC 913056.

- Shaughnessy, Jim (1997) [1982]. Delaware & Hudson. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-0455-6. OCLC 36008594.

Further reading

- Ruth, Phil Johnson (1997). Of Pulleys and Ropes and Gear: The Gravity Railroads of the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company and the Pennsylvania Coal Company. Honesdale, PA: Wayne County Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-9659540-0-6.