Education in early modern Scotland

Education in early modern Scotland includes all forms of education within the modern borders of Scotland, between the end of the Middle Ages in the late fifteenth century and the beginnings of the Enlightenment in the mid-eighteenth century. By the sixteenth century such formal educational institutions as grammar schools, petty schools and sewing schools for girls were established in Scotland, while children of the nobility often studied under private tutors. Scotland had three universities, but the curriculum was limited and Scottish scholars had to go abroad to gain second degrees. These contacts were one of the most important ways in which the new ideas of Humanism were brought into Scottish intellectual life. Humanist concern with education and Latin culminated in the Education Act 1496.

After the Reformation the Humanist concern with education became part of a programme of godly education, with an attempt to establish a system of parish schools administered by the Church of Scotland (the "Kirk"). A new university was established in Edinburgh and the existing universities underwent a series of reforms associated with Andrew Melville that revitalised them and brought them up to the standards of Humanist scholarship and methods of teaching of institutions elsewhere. In the seventeenth century there were attempts to organise and finance the system of parish schools and a successful expansion of the university system. By the early eighteenth century the network of parish schools was reasonably complete in the Lowlands, but limited in the Highlands where it was supplemented by Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Scotland began to reap the benefits of its university system, with major early figures of the Enlightenment including Francis Hutcheson, Colin Maclaurin and David Hume.

Background

Schooling

Surviving sources for education in Medieval Scotland are extremely limited. Outside of occasional references in documents concerned with other matters, they amount to a handful of burgh records and monastic and episcopal registers. In the Highlands there are indications of a system of Gaelic education associated with the professions of poetry and medicine, with ferleyn, who may have taught theology and arts, and rex scholarum of lesser status, but evidence of formal schooling is largely only preserved in place names.[1] By the end of the Middle Ages most large churches probably had song schools, open to all boys. Grammar schools, which were based on the teaching of Latin grammar for boys, could be found in all the main Scottish burghs and some small towns.[2] Educational provision was probably better in towns;[3] in rural areas, petty schools provided an elementary education.[4] They were almost exclusively aimed at boys, but by the end of the fifteenth century Edinburgh also had schools for girls. These were sometimes described as "sewing schools", whose name probably indicates one of their major functions, although reading may also have been taught,[3] and were generally run by lay women or nuns.[2][4] There was also the development of private tuition in the families of lords and wealthy burghers.[2] Sometimes these developed into "household schools" that may also have catered to farming neighbours and kin, as well as the sons of the laird's household. There is documentary evidence for about 100 schools of these different kinds before the Reformation.[1] The growing Humanist-inspired emphasis on education in the late Middle Ages culminated in the passing of the Education Act 1496, which decreed that all sons of barons and freeholders of substance should attend grammar schools and endorsed the Humanist concern to learn "perfyct Latyne". All this resulted in an increase in literacy, although it was largely concentrated among a male and wealthy elite,[2] with perhaps 60 per cent of the nobility being literate by the beginning of the sixteenth century.[5]

Universities

From the end of the eleventh century universities had been founded across Europe, developing as semi-autonomous centres of learning, often teaching theology, mathematics, law and medicine.[6] By the fifteenth century, beginning in northern Italy, universities had become strongly influenced by Humanist thinking. This put an emphasis on classical authors, questioned some of the accepted certainties of established thinking and manifested itself in the teaching of new subjects, particularly through the medium of the Greek language.[7] In the fifteenth century university colleges had been founded at St John's College, St Andrews (1418) and St Salvator's College was added in 1450. Glasgow was founded in 1451 and King's College, Aberdeen in 1495. St Leonard's College was added at St. Andrews in 1511. Initially, they were designed for the training of clerics, but they would increasingly be used by laymen who began to challenge the clerical monopoly of administrative posts in government and law.[8]

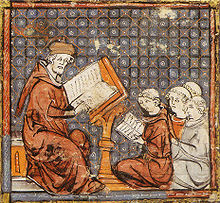

In this period Scottish universities largely had a Latin curriculum, designed for the clergy and civil and canon lawyers. They did not teach the Greek that was fundamental to the new Humanist scholarship, focusing on metaphysics, and putting a largely unquestioning faith in the works of Aristotle, whose authority would be challenged in the Renaissance.[9] They provided only basic degrees. Those wanting to study for the more advanced degrees that were common amongst European scholars needed to go to universities in other countries. As a result, large numbers of Scots continued their studies on the Continent and at English universities.[8] These international contacts helped integrate Scotland into a wider European scholarly world and would be one of the most important ways in which the new ideas of Humanism were brought into Scottish intellectual life.[5] By 1497 the Humanist and historian Hector Boece, born in Dundee and who had studied at Paris, returned to become the first principal at the new university of Aberdeen.[8] Another major figure was Archibald Whitelaw, a teacher at St. Andrews and Cologne who later became a tutor to the young James III and served as royal secretary from 1462 to 1493.[10]

Sixteenth century

Humanism and Protestantism

The civic values of humanism, which stressed the importance of order and morality, began to have a major impact on education and would become dominant in universities and schools by the end of the sixteenth century.[11] King's College Aberdeen was refounded in 1515. In addition to the basic arts curriculum it offered theology, civil and canon law and medicine.[12] St Leonard's College was founded in Aberdeen in 1511 by Archbishop Alexander Stewart. John Douglas led the refoundation of St John's College as St Mary's College, St Andrews in 1538, as a Humanist academy for the training of clerics, with a stress on biblical study.[13] Robert Reid, Abbot of Kinloss and later Bishop of Orkney, was responsible in the 1520s and 1530s for bringing the Italian humanist Giovanni Ferrario to teach at Kinloss Abbey, where he established an impressive library and wrote works of Scottish history and biography. Reid was also instrumental in organising the public lectures that were established in Edinburgh in the 1540s on law, Greek, Latin and philosophy, under the patronage of the queen consort Mary of Guise. These developed into the "Tounis College" of the city, which would eventually become the University of Edinburgh.[10]

In the mid-sixteenth century, Scotland underwent a Protestant Reformation that rejected Papal authority and many aspects of Catholic theology and practice. It created a predominately Calvinist national church, known as the kirk, which was strongly Presbyterian in outlook, severely reducing the powers of bishops, although not initially abolishing them.[14] This gave considerable power within the new kirk to local lairds, who often had control over the appointment of the clergy and would be important in establishing and funding schools.[15] There was also a shift from emphasis on ritual to one on the word, making the Bible, and the ability to read the Bible, fundamental to Scottish religion.[16]

Reformation of schools

The Humanist concern with increasing public access to education was shared by the Protestant reformers, who saw schools as vehicles for the provision of moral and religious education for a more godly society. After the Protestant party became dominant in 1560, the First Book of Discipline set out a plan for a school in every parish, but this proved financially impossible.[17] In the burghs the existing schools were largely maintained, with the song schools and a number of new foundations becoming reformed grammar schools or ordinary parish schools. Schools were supported by a combination of kirk funds, contributions from local heritors or burgh councils and parents that could pay. They were inspected by kirk sessions of local elders, which checked for the quality of teaching and doctrinal purity.[18] There were also large number of unregulated private "adventure schools". These were often informally created by parents in agreement with unlicensed schoolmasters, using available buildings and are chiefly evident in the historical record through complaints and attempts to suppress them by kirk sessions because they took pupils away from the official parish schools. However, such private schools were often necessary given the large populations and scale of some parishes. They were often tacitly accepted by the church and local authorities and may have been particularly important to girls and the children of the poor.[19] Outside of the established burgh schools, which were generally better funded and more able to pay schoolmasters, masters often combined their position with other employment, particularly minor posts within the kirk, such as clerk.[18] Immediately after the Reformation they were in short supply, but there is evidence that the expansion of the university system provided large numbers of graduates by the seventeenth century. There is evidence of about 800 schools for the period between 1560 and 1633. The parish schools were "Inglis" schools, teaching in the vernacular and taking children to the age of about 7, while the grammar schools took boys to about 12.[1] At their best in the grammar schools, the curriculum included the catechism, Latin, French, Classical literature and sports.[20]

The widespread belief in the limited intellectual and moral capacity of women came into conflict with a desire, intensified after the Reformation, for women to take greater personal moral responsibility, particularly as wives and mothers. In Protestantism this necessitated an ability to learn and understand the catechism and even to be able to independently read the Bible, but most commentators of the period, even those that tended to encourage the education of girls, thought they should not receive the same academic education as boys.[17] Girls were only admitted to parish schools when there were insufficient numbers of boys to pay an adequate living for schoolmasters. In the lower ranks of society, girls benefited from the expansion of the parish schools system that took place after the Reformation, but were usually outnumbered by boys and often taught separately, for a shorter time and to a lower level. Girls were frequently taught reading, sewing and knitting, but not writing.[21] Among the nobility there were many educated and cultured women, such as Mary, Queen of Scots.[22]

Reformation of universities

After the Reformation, Scotland's universities underwent a series of reforms associated with Andrew Melville, who returned from Geneva to become principal of the University of Glasgow in 1574. A distinguished linguist, philosopher and poet, he had trained in Paris and studied law at Poitiers, before moving to Geneva and developing an interest in Protestant theology. Influenced by the anti-Aristotelian Petrus Ramus, he placed an emphasis on simplified logic and elevated languages and sciences to the same status as philosophy, allowing accepted ideas in all areas to be challenged.[9] He introduced new specialist teaching staff, replacing the system of "regenting", where one tutor took the students through the entire arts curriculum.[23] Metaphysics were abandoned and Greek became compulsory in the first year followed by Aramaic, Syriac and Hebrew, launching a new fashion for ancient and biblical languages. Enrollment rates at the University of Glasgow had been declining before his arrival, but students now began to arrive in large numbers. He assisted in the reconstruction of Marischal College, Aberdeen founded as a second university college in the city in 1593 by George Keith, 5th Earl Marischal, and, in order to do for St Andrews what he had done for Glasgow, he was appointed Principal of St Mary's College, St Andrews in 1580.[10] The "Tounis College" established in the mid-sixteenth century became the University of Edinburgh in 1582.[10] Melville's reforms produced a revitalisation of all Scottish universities, which were now providing a quality of education equal to the most esteemed higher education institutions anywhere in Europe.[9]

Seventeenth century

Parish schools

In 1616 an act in Privy council commanded every parish to establish a school "where convenient means may be had". After the Parliament of Scotland ratified this law and the Education Act of 1633, a tax on local landowners was introduced to provide the necessary endowment.[24] From 1638 Scotland underwent a "second Reformation", with widespread support for a National Covenant, objecting to the Charles I's liturgical innovations and reaffirming the Calvinism and Presbyterianism of the kirk. After the Bishop's Wars (1639–40), Scotland had virtual independence from the government in Westminster.[25] Education remained fundamental to the ideas of the Covenanters. A loophole which allowed evasion of the education tax was closed in the Education Act of 1646, which established a solid institutional foundation for schools on Covenanter principles,[24] emphasising the role of presbyteries in supervision.[26] Although the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 brought a reversal to the 1633 position, in 1696 new legislation restored the provisions of 1646 together with means of enforcement "more suitable to the age" and underlined the aim of having a school in every parish. In rural communities these acts obliged local landowners (heritors) to provide a schoolhouse and pay a schoolmaster, known in Scotland as a dominie, while ministers and local presbyteries oversaw the quality of the education. In many Scottish towns, burgh schools were operated by local councils.[24] By the late seventeenth century there was a largely complete network of parish schools in the Lowlands, but in the Highlands basic education was still lacking in many areas.[27]

Growth of the universities

Under the Commonwealth (1652–60), the universities saw an improvement in their funding, as they were given income from deaneries, defunct bishoprics and the excise, allowing the completion of buildings including the college in the High Street in Glasgow. They were still largely seen as training schools for clergy, and came under the control of the hard line Protesters, who were generally favoured by the regime because of their greater antipathy to royalism, with leading protester Patrick Gillespie being made Principal at Glasgow in 1652.[28] After the Restoration there was a purge of Presbyterians from the universities, but most of the intellectual advances of the preceding period were preserved.[29] The five Scottish universities recovered from the disruption of the civil war years and Restoration with a lecture-based curriculum that was able to embrace economics and science, offering a high-quality liberal education to the sons of the nobility and gentry.[27] All saw the establishment or re-establishment of chairs of mathematics. Astronomy was facilitated by the building of observatories at St. Andrews and at King's and Marischal colleges in Aberdeen. Robert Sibbald was appointed as the first Professor of Medicine at Edinburgh and he co-founded the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh in 1681.[30] These developments helped the universities to become major centres of medical education and would put Scotland at the forefront of Enlightenment thinking.[27]

Early eighteenth century

Limitations of the school system

One of the effects of the extensive network of parish schools was the growth of the "democratic myth", which in the nineteenth century created the widespread belief that many a "lad of pairts" had been able to rise up through the system to take high office and that literacy was much more widespread in Scotland than in neighbouring states, particularly England.[27] Historians now accept that very few boys were able to pursue this route to social advancement and that literacy was not noticeably higher than in comparable nations, as the education in the parish schools was basic and short and attendance was not compulsory.[31]

By the eighteenth century many poorer girls were being taught in dame schools, informally set up by a widow or spinster to teach reading, sewing and cooking.[32] Among members of the aristocracy by the early eighteenth century a girl's education was expected to include basic literacy and numeracy, needlework, cookery and household management, while polite accomplishments and piety were also emphasised.[33] Female illiteracy rates based on signatures among female servants were around 90 percent from the late seventeenth to the early eighteenth centuries, and perhaps 85 percent for women of all ranks by 1750, compared with 35 per cent for men.[21] Overall literacy rates were slightly higher than in England as a whole, but female rates were much lower than for their English counterparts.[34]

In the Scottish Highlands, popular education was challenged by problems of distance and physical isolation, as well as teachers' and ministers' limited knowledge of Scottish Gaelic, the primary local language. Here the Kirk's parish schools were supplemented by those established from 1709 by the Scottish Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Its aim in the Highlands was to teach English language and end the attachment to Roman Catholicism associated with rebellious Jacobitism. Though the SSPCK schools eventually taught in Gaelic, the overall effect contributed to the erosion of Highland culture.[35] Literacy rates were lower in the Highlands than in comparable Lowland rural society, and despite these efforts illiteracy remained prevalent into the nineteenth century.[36]

Beginnings of the Enlightenment

Access to Scottish universities was probably more open than in contemporary England, Germany or France. Attendance was less expensive and the student body more representative of society as a whole.[37] In the eighteenth century Scotland reaped the intellectual benefits of this system in its contribution the European Enlightenment.[38] Key figures in the Scottish Enlightenment who had made their mark before the mid-eighteenth century included Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746), who was professor of moral philosophy at Glasgow from 1729 to 1746. He was an important link between the ideas of Shaftesbury and the later school of Scottish Common Sense Realism, developing Utilitarianism and Consequentialist thinking. Colin Maclaurin (1698–1746), appointed to a chair of mathematics by the age of 19 at Marischal College, was the leading British mathematician of his era. Perhaps the most significant intellectual figure of early modern Scotland was David Hume (1711–76) whose Treatise on Human Nature (1738) and Essays, Moral and Political (1741) helped outline the parameters of philosophical Empiricism and Scepticism.[39] He would be a major influence of later Enlightenment figures including Adam Smith, Immanuel Kant and Jeremy Bentham.[40]

Notes

- ^ a b c S. Murdoch, "Schools and schooling: I to 1696", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 561–3.

- ^ a b c d P. J. Bawcutt and J. H. Williams, A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry (Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006), ISBN 1-84384-096-0, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b E. Ewen, "'Hamperit in ane hony came': sights, sounds and smells in the Medieval town", in E. J. Cowan and L. Henderson, A History of Everyday Life in Medieval Scotland: 1000 to 1600 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011), ISBN 0748621571, p. 126.

- ^ a b M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (New York, NY: Random House, 2011), ISBN 1-4464-7563-8, pp. 104–7.

- ^ a b J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 68–72.

- ^ I. Wei, "The rise of universities" in A. MacKay, ed., Atlas of Medieval Europe (London: Routledge, 1997), ISBN 0415019230, pp. 241–3.

- ^ W. Rüegg, "The rise of Humanism", in Hilde de Ridder-Symoens, ed., A History of the University in Europe: Volume 1, Universities in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), ISBN 0521541131, pp. 452–9.

- ^ a b c B. Webster, Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity (St. Martin's Press, 1997), ISBN 0-333-56761-7, pp. 124–5.

- ^ a b c J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 183–4.

- ^ a b c d A. Thomas, The Renaissance, in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0-19-162433-0, pp. 196–7.

- ^ J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748614559, pp. 340–1.

- ^ J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748614559, p. 55.

- ^ J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748614559, p. 187.

- ^ J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 102–4.

- ^ J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 121–33.

- ^ G. D. Henderson, Religious Life in Seventeenth-Century Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), ISBN 0521248779, pp. 1–4.

- ^ a b R. A. Houston, Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-521-89088-8, p. 5.

- ^ a b M. Todd, The Culture of Protestantism in Early Modern Scotland (Yale University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-300-09234-2, pp. 59–62.

- ^ R. A. Houston, Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-521-89088-8, pp. 115–6.

- ^ J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 183–3.

- ^ a b R. A. Houston, Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), ISBN 0521890888, pp. 63–8.

- ^ K. Brown, Noble Society in Scotland: Wealth, Family and Culture from Reformation to Revolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), ISBN 0748612998, p. 187.

- ^ J. Kirk, "'Melvillian reform' and the Scottish universities", in A. A. MacDonald and M. Lynch, eds, The Renaissance in Scotland: Studies in Literature, Religion, History, and Culture Offered to John Durkhan (BRILL, 1994), ISBN 90-04-10097-0, p. 280.

- ^ a b c "School education prior to 1873", Scottish Archive Network, 2010, archived from the original on 2 July 2011.

- ^ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, p. 204.

- ^ J. R. Young, "The Covenanters and the Scottish Parliament 1639–51: the rule of the Godly and the second Scottish Reformation", in E. Boran and C. Gribben, Enforcing Reformation in Ireland and Scotland: 1550–1700 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006), ISBN 0754682234, p. 143.

- ^ a b c d R. Anderson, "The history of Scottish Education pre-1980", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, Scottish Education: Post-Devolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1625-X, pp. 219–28.

- ^ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 227–8.

- ^ M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (Random House, 2011), ISBN 1-4464-7563-8, p. 262.

- ^ T. M. Devine, "The rise and fall of the Scottish Enlightenment", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0-19-162433-0, p. 373.

- ^ T. M. Devine, The Scottish Nation, 1700–2000 (London: Penguin Books, 2001), ISBN 0-14-100234-4, pp. 91–100.

- ^ B. Gatherer, "Scottish teachers", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, Scottish Education: Post-Devolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1625-X, p. 1022.

- ^ K. Glover, Elite Women and Polite Society in Eighteenth-Century Scotland (Boydell Press, 2011), ISBN 1843836815, p. 26.

- ^ R. A. Houston, Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), ISBN 0521890888, p. 72.

- ^ C. Kidd, British Identities Before Nationalism: Ethnicity and Nationhood in the Atlantic World, 1600–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), ISBN 0521624037, p. 138.

- ^ R. A. Houston, Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), ISBN 0521890888, p. 70.

- ^ R. A. Houston, Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-521-89088-8, p. 245.

- ^ A. Herman, How the Scots Invented the Modern World (London: Crown Publishing Group, 2001), ISBN 0-609-80999-7.

- ^ R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, p. 150.

- ^ B. Freydberg, David Hume: Platonic Philosopher, Continental Ancestor (Suny Press, 2012), ISBN 1438442157, p. 105.