Englemann Canyon

Englemann Canyon (also spelled Engleman's Canon)[1][2] is a valley along Ruxton Creek, in Manitou Springs, El Paso County, Colorado.[3] It is one of three canyons in Manitou Springs, the others are Ute Pass and Williams Canyon.[4]

Upper Englemann Canyon

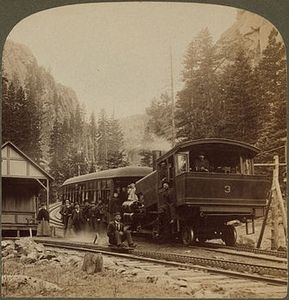

In 1880, a trail was opened in Englemann Canyon to Pikes Peak.[5] It was called the Manitou Trail in 1883.[6] Zalmon Simmons surveyed the canyon for telegraph lines. The Civil War veteran and later inventor of the Simmons mattress decided that the canyon was suited for construction of a cog railway.[7] The Manitou and Pike's Peak Railway, built by Simmons and completed in 1890, begins in Englemann Canyon and follows Ruxton Creek up into the Rocky Mountains for Pikes Peak.[8] The railroad climbs at a 6% grade through the canyon past "stately spruces and jagged rocks".[9] The first third of the 8.9 miles (14.3 km) railway trip is through Englemann Canyon, alongside Ruxton Creek. Scenery includes large boulders, Ponderosa pine trees, Englemann spruce, and Colorado blue spruce.[10] Sights in the canyon include Artist Glen, Minnehaha Falls, Son-of-a-Gun Hill, Hells Gate, the site of Halfway House, and Ruxton Park.[10][11][12] Artist Glen was the 160 acre home and bed and breakfast along Ruxton Creek of artist and photographer William Hook and his family during the late 19th century. Some of its guests were delivered by burros via a Pikes Pike burro trail near their home. The accommodations became less desirable when the cog railway was built about 30 feet from the house.[13] The Halfway House was a rustic hotel that served tourists who took the railway.[14][13] Minnehaha, named for its falls, was a hamlet with several cabins.[14]

In 1891, the canyon was described in The Illustrated American as "a narrow valley, with a steep mountain rising on either side, and the clear, sparkling Ruxton Creek rushing parallel to the track, sometimes dashing over rocks hundreds of feet below the train, and sometimes pausing for a moment to form a deep, smooth pool, such as the speckled trout loves to haunt."[15]

-

Manitou and Pike's Peak Railway depot on Ruxton Avenue, 1894

-

Halfway House, Ruxton Park, Colorado, by 1915

-

Manitou and Pike's Peak Railway, 2006

In 1925, a water utility power plant was built in Ruxton Park for $16,866 equivalent to $293,027 in 2023 by the city of Colorado Springs.[16][17] The stone hydroelectric plant generates electricity as Ruxton Creek flows into Manitou Springs from the mountain.[a]

Lower Englemann Canyon

In the early 20th century, an electric trolley of the Colorado Springs and Interurban Railway from Colorado Springs terminated at Manitou Springs, and a trolley, called the "Dinky" carried passengers up lower Englemann Canyon (Ruxton Road) to the Manitou and Pike's Peak Railway depot.[14][19]

In 1891 the canyon had one spring, the Ute-Iron spring,[20] Near the depot there were three mineral springs in 1913: Ute-Iron, Little Chief, and Ouray springs.[21] near the Iron Springs Hotel.[22] The current Manitou Mineral Springs on Ruxton Avenue are Iron Spring and Twin Spring.[23][24]

Notes

- ^ In 1957, it generated up to 1,250 kilowatts and the Manitou Hydroelectric Plant produced up to 5,000 kilowatts. The two plants supplied up to 4% of the Pikes Peak Region's electricity. The majority of the region's electricity was supplied by two steam plants in Colorado Springs. When the water levels rise, though, the plants can supply more electricity. During the Memorial Day 1935 flood, the two plants supplied electricity for two weeks to the Pikes Peak region.[18]

References

- ^ Cassier's Magazine. 1894. p. 109.

- ^ Alexander Majors (1893). Seventy Years on the Frontier: Alexander Major's Memoirs of a Lifetime on the Border. Rand, McNally. p. 308.

- ^ "Englmann Canyon". Geographical Names Information System, US Geological Survey, US Department of the Interior. October 13, 1878. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ^ Frederick Converse Beach; George Edwin Rines (1912). The Americana: a universal reference library, comprising the arts and sciences, literature, history, biography, geography, commerce, etc., of the world. Scientific American compiling department. p. 427.

- ^ Frederick Hastings Chapin (1995). Frederick Chapin's Colorado: The Peaks About Estes Park and Other Writings. University Press of Colorado. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-87081-366-5.

- ^ Samuel Edwin Solly (1883). The Health resorts of Colorado Springs and Manitou. Gazette Publishing Company. p. 19.

- ^ Tim Blevins (1 January 2012). Film & Photography on the Front Range. Pikes Peak Library District. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-56735-297-9.

- ^ Monahan, Sherry (2002). Pikes Peak: Adventures, Communities, and Lifestyles (Google books). p. 10. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ^ Phelps R. Griswold; Bob Griswold (1988). Railroads of Colorado: A Guide to Modern and Narrow Gauge Trains. American Traveler Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-55838-088-2.

- ^ a b "Along the Route". Manitou & Pike's Peak Railway. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ^ "Ride the Cog Rail to the Summit of Pikes Peak: The Trip to the Summit of Pikes Peak". Pikes Peak - America's Mountain. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ^ "Digital Collection Search: Englemann Canyon". Denver Public Library. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ^ a b Tim Blevins (1 January 2012). Film & Photography on the Front Range. Pikes Peak Library District. pp. 53–60. ISBN 978-1-56735-297-9.

- ^ a b c Manitou and Cog Wheel Route Pike's Peak Railway, The Committee of One Hundred (1915). Stop at Pike's Peak on your Way to or from the Expositions (for 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition). Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ^ "Up Pike's Peak by Rail". The Illustrated American. Illustrated American Publishing Company. 1891. p. 165.

- ^ R. Scott Rappold (November 1, 2008). "The Power of Privacy". The Gazette. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ Mel McFarland, Historian (December 8, 2014). "Cobweb Corners: The old Half Way House in Ruxton Park". Westside Pioneer. Colorado Springs, CO. Retrieved January 2015.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Harry Kliewer Has run Manitou hydro plant for last 30 years" (PDF). Colorado Springs Free Press. Colorado Springs, Colorado. February 8, 1957. p. 8 – via Pikes Peak Library District: Pikes Peak NewsFinder.

- ^ "Stratton Spring". Manitou Mineral Springs. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ^ Colorado College (1891). Colorado College Studies: Papers read before the Colorado College Scientific Society. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The Inland Press, The Register Publishing Company. p. 17.

- ^ Colorado Scientific Society. Proceedings of the Colorado Scientific Society. Vol. X - 1911, 1912, 1913. Denver, Colorado: The Society. p. 241.

- ^ Tourists' Hand Book of Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. The Railway. 1887. p. 26.

- ^ "Manitou Mineral Springs (brochure)" (PDF). Manitou Mineral Springs. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ^ "Mineral Content Chart" (PDF). Manitou Mineral Springs. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

External links

- Englemann Canyon, topographic map

| External images | |

|---|---|