Filippo Lippi

Fra' Filippo Lippi, O.Carm. | |

|---|---|

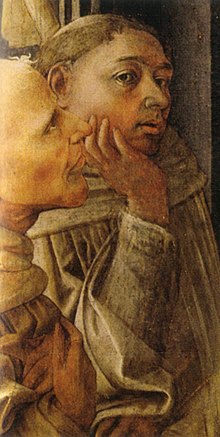

Selfportrait of Fra' Filippo Lippi | |

| Born | Filippo Lippi ca. 1406 |

| Died | 8 October 1469 (aged 59–60) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Painting, Fresco |

| Notable work | Madonna and Child Enthroned, Annunciation |

| Movement | Early Renaissance |

Fra' Filippo Lippi, O.Carm. (c. 1406 – 8 October 1469), also called Lippo Lippi, was an Italian painter of the Quattrocento (15th century).

Biography and works

Lippi was born in Florence around 1406 to Tommaso, a butcher, and his wife. Both his parents died when he was still a child. Mona Lapaccia, his aunt, who being too poor to rear him placed him at the age of eight in the neighbouring Carmelite convent, where he was educated. In 1420 he was admitted to the community of Carmelite friars of the Priory of Our Lady of Mount Carmel in Florence, taking religious vows in the Order the following year, at the age of sixteen. He would have been ordained a priest sometime around 1425, and was to remain in residence in that priory until 1432.[1] Vasari writes that Lippi was inspired to become a painter by watching Masaccio at work in the Carmine church, and his early work, notably the Tarquinia Madonna (Galleria Nazionale, Rome) shows his influence.[2] In his Lives of the Artists, Vasari says: "Instead of studying, he spent all his time scrawling pictures on his own books and those of others."[3] The prior decided to give him the opportunity to learn painting.

Eventually Fra Filippo quit the monastery, but it appears he was not released from his vows; in a letter dated 1439 he describes himself as the poorest friar of Florence, charged with the maintenance of six marriageable nieces. The altarpiece Lippi painted in 1441 for the nuns of S. Ambrogio is now a prominent attraction in the Academy of Florence, and was celebrated in Browning's well-known poem Fra Lippo Lippi. It represents the coronation of the Virgin among angels and saints, including many Bernardine monks. One of these, placed to the right, is a half-length portrait of Lippo, pointed out by the inscription perfecit opus upon an angel's scroll. The price paid for this work was 1200 Florentine livre.

In 1452 he was appointed chaplain to the nuns at the Monastery of St. Mary Magdalene in Florence, and in 1457 commendatory Rector (Rettore commendatario) of S. Quirico in Legania, from which institutions he occasionally made considerable profits; but his poverty seems to have been chronic. His paintings were popular in Florence and he was supported by the Medici family, who commissioned of The Annunciation and the Seven Saints. To compel him to work Cosimo de' Medici locked him up, and even then the painter escaped by a rope made of his sheets. His escapades threw him into financial difficulties from which he did not hesitate to extricate himself by forgery[why?].[1] His life is a tale of lawsuits, complaints, broken promises and scandal.[2]

Vasari relates Lippi's visits to Ancona and Naples, his capture by Barbary pirates and enslavement in Barbary, where his skill in portrait-sketching helped to release him[why?].[5] Louis Gillet, writing for the Catholic Encyclopedia, considers this account "assuredly nothing but a romance".[1] From 1431 to 1437 his career is not accounted for.

In June 1456 Fra Filippo is recorded as living in Prato (near Florence) to paint frescoes in the choir of the cathedral. In 1458, while engaged in this work, he set about painting a picture for the monastery chapel of S. Margherita in that city, where he met Lucrezia Buti, the beautiful daughter of a Florentine named Francesco Buti; she was either a novice of the Order or a young lady placed under the nuns' guardianship. Lippi asked that she might be permitted to sit for the figure of the Madonna (or perhaps S. Margherita). Under that pretext, Lippi engaged in sexual relations with her, abducted her to his own house, and kept her there despite the nuns' efforts to reclaim her.[6] The result was their son Filippino Lippi, who became a painter no less famous than his father. Such is Vasari's narrative, published less than a century after the alleged events.

The frescoes in the choir of the cathedral of Prato, which depict the stories of St. John the Baptist and St. Stephen on the two main facing walls, are considered Fra Filippo's most important and monumental works, particularly the figure of Salome dancing, which has clear affinities with later works by Sandro Botticelli, his pupil, and Filippino Lippi, his son, as well as the scene showing the ceremonial mourning over Stephen's corpse. This latter is believed to contain a portrait of the painter, but there are various opinions as to which is the exact figure. On the end wall of the choir are S. Giovanni Gualberto and S. Alberto, while the vault has monumental representations of the four evangelists.[6]

The close of Lippi's life was spent at Spoleto, where he had been commissioned to paint, for the apse of the cathedral, scenes from the life of the Virgin. In the semidome of the apse is the Christ Crowning the Madonna, with angels, sibyls and prophets. This series, which is not wholly equal to the one at Prato, was completed by one of his assistants, his fellow Carmelite, Fra Diamante, after Lippi's death. That Lippi died in Spoleto, on or about the 8th of October 1469, is a fact; the mode of his death is a matter of dispute. It has been said that the pope granted Lippi a dispensation for marrying Lucrezia, but before the permission arrived, Lippi had been poisoned by the indignant relatives of either Lucrezia herself or some lady who had replaced her in the inconstant painter's affections.[6]

For Germiniano Inghirami of Prato he painted the Death of St. Bernard. His principal altarpiece in this city is a Nativity in the refectory of S. Domenico — the Infant on the ground adored by the Virgin and Joseph, between Saints George and Dominic, in a rocky landscape, with the shepherds playing and six angels in the sky. In the Uffizi is a fine Virgin adoring the infant Christ, who is held by two angels; in the National Gallery, London, a Vision of St Bernard. The picture of the Virgin and Infant with an Angel, in this same gallery, also ascribed to Lippi, is disputable.

Filippo Lippi died in 1469 while working on the frescoes of Scenes of the Life of the Virgin Mary, 1467–1469 in the apse of the Spoleto Cathedral. The Frescos show the Annunciation, the Funeral, the Adoration of the Child and the Coronation of the Virgin. A group of bystanders depicted at the funeral includes a self-portrait of Lippi, together with his son Filippino and his helpers, Fra Diamante and Pier Matteo d'Amelia. Lippi was buried on the right side of the transept, with a monument commissioned by Lorenzo de' Medici.[3] Francesco di Pesello (called Pesellino) and Sandro Botticelli were among his most distinguished pupils.

Selected works

- Madonna and Child Enthroned (Madonna of Tarquinia) (1437) -Tempera on panel, 151 x 66 cm, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Rome

- Madonna and Child with Saints (1438) - Panel, 208 x 244 cm, Louvre, Paris

- St. Jerome in Penance (c. 1439) - Tempera on panel, 54 x 37 cm, Lindenau Museum, Altenburg

- The Annunciation with two Kneeling Donors (c. 1440) - Oil on panel, 155 x 144 cm, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Rome

- Martelli Annunciation (c. 1440) - Tempera on panel, 175 x 183 cm, San Lorenzo, Florence

- Coronation of the Virgin (1441–1447) - Tempera on panel, 200 x 287 cm, Uffizi, Florence

- Annunciation (c. 1443–1450) - Wood, 203 x 185.3 cm, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

- Marsuppini Coronation (after 1444) - Tempera on panel, 172 x 251 cm, Pinacoteca Vaticana, Rome

- Annunciation (1445–50) - Oil on panel, 117 x 173 cm, Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome

- Annunciation (c. 1449–1459) - Tempera on panel, 68 x 151.5 cm, National Gallery, London

- Seven Saints (c. 1449–1459) - Tempera on panel, 68 x 151.5 cm, National Gallery, London

- Madonna and Child (c. 1452) - Panel, diameter 135 cm, Pitti Gallery, Florence

- Funeral of St. Jerome (c. 1452–1460) - Tempera on panel, 268 x 165 cm, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Prato Cathedral

- Stories of St. Stephen and St. John the Baptist (1452–1465) - Fresco cycle, Cathedral of Prato

- Madonna del Ceppo (c. 1452–1453) - Panel, 187 x 120 cm, Civic Museum, Prato

- Madonna and Child (c. 1455) - Panel, Uffizi, Florence

- Adoration in the Forest (late 1450s) - Panel, 127 x 116 cm, Staatliche Museen, Berlin

- Madonna of Palazzo Medici-Riccardi (1466–1469) - Tempera on panel, 115 x 71 cm, Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Florence

- Scenes of the Life of the Virgin Mary (1467–1469) - Fresco, apse of the Spoleto Cathedral

- Madonna and Child (between circa 1446 and circa 1447), The Walters Art Museum.

- Triptych of the Madonna of Humility with saints

-

Madonna with the Child and two Angels (1465), tempera on wood, Uffizi.

-

Portrait of a woman

-

Coronation of the Virgin (detail)

-

Madonna with Child

-

Madonna and Child Follower of Fra Filippo Lippi and Francesco Pesellino

Notes

- ^ a b c Gillet, Louis. "Filippo Lippi". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. Retrieved 4 April 2015

- ^ a b "Fra Filippo Lippi", The National Gallery, London

- ^ a b "Filippo Lippi", Virtual Uffizi Gallery

- ^ "Madonna and Child". The Walters Art Museum.

- ^ Greene, Robert (2000). The 48 Laws of Power. Penguin Books. p. 187. ISBN 0-14-028019-7.

- ^ a b c "Fra Filippo Lippi Biography", Frafilippolippi.org

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

- Canaday (1969). The Lives of the Painters Vol. 1. New York: Norton and Company.

- Kleiner, Fred S.; Mamiya, Christian J. (2005). Art Through the Ages. Thomson & Wadsworth. ISBN 0534167055.

- Hartt, Frederick (1980). The History of Italian Renaissance Art. London: Thames and Hudson.

Further reading

- Ruda, Jeffrey (1993). Fra Filippo Lippi: Life and Work. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 0714838896.

Historical novels

- Proud, Linda (2012). A Gift for the Magus. Godstow Press. ISBN 9781907651038. [A literary novel about Filippo Lippi and Cosimo de' Medici.]

External links

- www.FraFilippoLippi.org 75 works by Filippo Lippi

- Paul George Konody, Filippo Lippi, London: T.C. & E.C. Jack; New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1911.

- Italian Paintings: Florentine School, a collection catalog containing information about Lippi and his works (see pages: 92–94).