Flexural strength

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2008) |

Flexural strength, also known as modulus of rupture, or bend strength, or transverse rupture strength is a material property, defined as the stress in a material just before it yields in a flexure test.[1] The transverse bending test is most frequently employed, in which a specimen having either a circular or rectangular cross-section is bent until fracture or yielding using a three point flexural test technique. The flexural strength represents the highest stress experienced within the material at its moment of failure. It is measured in terms of stress, here given the symbol .

Introduction

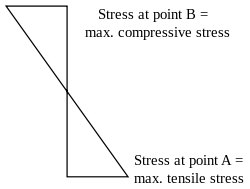

When an object formed of a single material, like a wooden beam or a steel rod, is bent (Fig. 1), it experiences a range of stresses across its depth (Fig. 2). At the edge of the object on the inside of the bend (concave face) the stress will be at its maximum compressive stress value. At the outside of the bend (convex face) the stress will be at its maximum tensile value. These inner and outer edges of the beam or rod are known as the 'extreme fibers'. Most materials fail under tensile stress before they fail under compressive stress, so the maximum tensile stress value that can be sustained before the beam or rod fails is its flexural strength.[citation needed]

Flexural versus tensile strength

The flexural strength would be the same as the tensile strength if the material were homogeneous. In fact, most materials have small or large defects in them which act to concentrate the stresses locally, effectively causing a localized weakness. When a material is bent only the extreme fibers are at the largest stress so, if those fibers are free from defects, the flexural strength will be controlled by the strength of those intact 'fibers'. However, if the same material was subjected to only tensile forces then all the fibers in the material are at the same stress and failure will initiate when the weakest fiber reaches its limiting tensile stress. Therefore, it is common for flexural strengths to be higher than tensile strengths for the same material. Conversely, a homogeneous material with defects only on its surfaces (e.g., due to scratches) might have a higher tensile strength than flexural strength.

If we don't take into account defects of any kind, it is clear that the material will fail under a bending force which is smaller than the corresponding tensile force. Both of these forces will induce the same failure stress, whose value depends on the strength of the material.

For a rectangular sample, the resulting stress under an axial force is given by the following formula:

This stress is not the true stress, since the cross section of the sample is considered to be invariable (engineering stress).

- is the axial load (force) at the fracture point

- b is width

- d is the depth or thickness of the material

The resulting stress for a rectangular sample under a load in a three-point bending setup (Fig. 3) is given by the formula below (see "Measuring flexural strength").

The equation of these two stresses (failure) yields:

Usually, L (length of the support span) is much bigger than d, so the fraction is bigger than one.

Measuring flexural strength

For a rectangular sample under a load in a three-point bending setup (Fig. 3):

- F is the load (force) at the fracture point (N)

- L is the length of the support span

- b is width

- d is thickness

For a rectangular sample under a load in a four-point bending setup where the loading span is one-third of the support span:

- F is the load (force) at the fracture point

- L is the length of the support (outer) span

- b is width

- d is thickness

For the 4 pt bend setup, if the loading span is 1/2 of the support span (i.e. Li = 1/2 L in Fig. 4):

If the loading span is neither 1/3 nor 1/2 the support span for the 4 pt bend setup (Fig. 4):

- Li is the length of the loading (inner) span

See also

References

- ^ Michael Ashby (2011). Materials selection in mechanical design. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 40.

- J. M. Hodgkinson (2000), Mechanical Testing of Advanced Fibre Composites, Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing, Ltd., p. 132–133.

- William D. Callister, Jr., Materials Science and Engineering, Hoken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2003.

- ASTM C1161-02c(2008)e1, Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Advanced Ceramics at Ambient Temperature, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA.