Flight to Mars (film)

| Flight to Mars | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Lesley Selander |

| Screenplay by | Arthur Strawn |

| Produced by | Walter Mirisch |

| Starring | Marguerite Chapman Cameron Mitchell Arthur Franz |

| Cinematography | Harry Neumann |

| Edited by | Richard Heermance |

| Music by | Marlin Skiles |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Monogram Distributing |

Release date |

|

Running time | 72 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

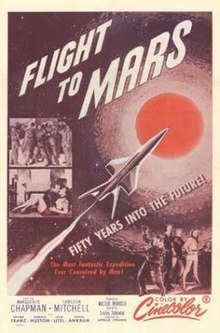

Flight to Mars is a 1951 American Cinecolor science fiction film drama, produced by Walter Mirisch for Monogram Pictures, directed by Lesley Selander, that stars Marguerite Chapman, Cameron Mitchell, and Arthur Franz.[1]

The film's storyline involves the arrival on the Red Planet of an American scientific expedition team, who discover that Mars is inhabited by an underground-dwelling but dying civilization that appears to be humanoid. The Martians are suspicious of the Earthmen's motives. A majority of their governing body finally decides to keep their visitors prisoner, never allowing them to return home with the information they have discovered. But the Earthmen have sympathizers among the Martians. Soon a plan is set in motion to smuggle the scientists and their Martian allies aboard the guarded spaceship and to make an escape for Earth.

Plot

[edit]The first expedition to Mars, led by physicist Dr. Lane, includes Professor Jackson, engineer and spaceship designer Jim Barker, and his assistant Carol Stafford, who earned her degree in "spaceship engineering" in only three years. Journalist Steve Abbott, a decorated (Korean) war correspondent, is also aboard to cover the historic mission.

They lose contact with Earth when a meteor storm disables both their landing gear and radio. The crew are forced to decide whether to crash-land on Mars or turn back for Earth. They decide to proceed with the mission, knowing they may never return.

After they safely crash-land, the crew are met by five Martians at one of their above-ground structures. Looking human and being able to communicate in English, Ikron, the president of their planetary council, explains that they learned Earth languages from broadcasts. Their own efforts, however, to transmit messages to Earth have only resulted in faint, unintelligible signals being received.

The Earth crew are taken to a vast underground city, which is being sustained by life-support systems fueled by a (fictional) mineral called Corium, from which the Martians extract water and air, and generate energy. There the crew meet Tillamar, a past president and now a trusted council advisor. Terris, a young female Martian, shows them to their room and serves the group automated meals. The expedition members are amazed at the high level of Martian technology around them and soon ask the council for help with repairing their spaceship.

Discreetly, Ikron reveals that their Corium supply is nearly depleted. He recommends that the Earthmen's spaceship, once repaired, be reproduced, thereby creating a fleet that can evacuate the Martians to Earth, thereby saving the Martian species, but also enslaving the Terran species. The council votes to adopt Ikron's plan, while also deciding to hold the Earthmen captive during the repair process. Alita, a leading Martian scientist, is placed in charge of the spaceship. Ikron uses Terris as a spy to keep himself informed of the progress. Meanwhile, Jim begins to suspect the Martians' motives and, with Alita's help, fakes an explosion aboard, slowing the repairs. When Jim later announces their blast-off for Earth is set for the next day, he surprises everyone with the news that Tillamar and Alita will be joining them, with Alita to become his wife.

Terris reports their suspicious behavior to Ikron, leading to Alita and Tillamar being held, but Jim foils Ikron's plan to seize the repaired ship after freeing both. After a brief confrontation with Martian guards at the spaceship's gangway, the three make it aboard safely, and the expedition departs for Earth.

Cast

[edit]- Marguerite Chapman as Alita

- Cameron Mitchell as Steve Abbott

- Arthur Franz as Dr. Jim Barker

- Virginia Huston as Carol Stafford

- John Litel as Dr. Lane

- Morris Ankrum as Ikron

- Richard Gaines as Professor Jackson

- Lucille Barkley as Terris

- Robert Barrat as Tillamar

- Wilbur Back as Councilman

- William Bailey as Councilman

- Trevor Bardette as Alzar

- Stanley Blystone as Councilman

- David Bond as Ramay

- Raymond Bond as Astronomer No. Two

Production

[edit]Flight to Mars has some plot similarities to the Russian silent film Aelita, but unlike that earlier film it is a low-budget "quickie" shot in just five days.[2]

The film's on location principal photography took place in Death Valley, California from May 11 through late May 1951.[3]

Except for some of the flight instruments, Flight to Mars reuses the interior flight deck sets, somewhat redressed, and other interior props from Lippert Pictures' 1950 science fiction feature Rocketship X-M. Even that earlier film's spaceflight sound effects are reused, as are the concepts of space flight outlined in RX-M's screenplay. The main difference is this film was shot in color, not black-and-white, and the flight to Mars was planned; the earlier Lippert film concerns an accidental journey to the Red Planet, which happens during a planned expedition to the Moon. Additionally, Flight to Mars postulates a humanoid species which is superior, in many ways, to humanity, and may possibly pose a long-term, strategic threat. In the Lippert film, however, the Martians are a throw-back, a consequence of a long ago nuclear holocaust, that occurred millennia earlier; those Martians pose only an immediate, tactical threat to the RX-M's crew.[4]

A sequel, Voyage to Venus, was proposed but never made.[5]

Reception

[edit]Variety wrote: "Presentation is on a standard level, with stock situations and excitement, but physically film looks better than the usual ligh tbudgeted effort through a well-conceived production design that displays technical gadgets and settings nicely. Cinecolor hues also help values. Lesley Selander's direction of the Arthur Strawn screenplay keeps it moving along at a fairly good pace, although surfeit of dialog occasionally slows it down."[6]

The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote: "A science fiction adventure on the comic strip level, with dialogue, playing and use of colour to match. The technical effects are poorly managed, with little attempt to sustain any illusion, and Mars itself looks like a futuristic Ideal Home Exhibition run up in cardboard."[7]

See also

[edit]- 1951 in film

- List of films set on Mars

- List of science fiction films of the 1950s

- Mission to Mars, a 2000 film with a similar premise.

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Flight to Mars". American Film Institute Catalog. Retrieved 5 October 2024.

- ^ Weaver 2003, pp. 210–211.

- ^ "Original print information: Flight to Mars." Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved: January 7, 2015.

- ^ Muirhead et al. 2004, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Weaver 2003, p. 212.

- ^ "Flight to Mars". Variety. 184 (9): 18. 7 November 1951 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Flight to Mars". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 19 (216): 64. 1 January 1952 – via ProQuest.

Bibliography

[edit]- Miller, Thomas Kent. Mars in the Movies: A History. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2016. ISBN 978-0-7864-9914-4.

- Muirhead, Brian, Judith and Garfield Reeves-Stevens. Going to Mars: The Stories of the People Behind NASA's Mars Missions Past, Present, and Future. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004. ISBN 978-0-67102-796-4.

- Warren, Bill. Keep Watching the Skies: American Science Fiction Films of the Fifties, 21st Century Edition. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2009 (First Edition 1982). ISBN 0-89950-032-3.

- Weaver, Tom. "Cameron Mitchell Interview". Double Feature Creature Attack: A Monster Merger of Two More Volumes of Classic Interviews. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003. ISBN 978-0-78641-366-9.

External links

[edit]- 1951 films

- 1950s science fiction films

- Allied Artists films

- American science fiction films

- Cinecolor films

- 1950s English-language films

- Films about astronauts

- Films about extraterrestrial life

- Films directed by Lesley Selander

- Films produced by Walter Mirisch

- American independent films

- Mars in film

- Monogram Pictures films

- 1951 independent films

- 1950s American films

- English-language science fiction films