Frederik de Wit

Frederick de Wit (1629/1630 – 1706) was a cartographer and artist who drew, printed and sold maps.[1] On maps his name is also written Frederic, Frederik, Frederico and Fredericus (Latinised). His surname is also written as de Witt and de Widt.

He was born in Gouda and died in Amsterdam. He was the company founder.[2]

Early years and the founding of the company

Frederick de Wit was born Frederick Hendricksz or Frederick son of Hendrick. He was born to a Protestant family in 1629/30, in Gouda, a small city in the province of Holland, one of the seven united provinces of the Netherlands. His father Hendrick Fredericsz (1608 - 29 July1668)[3] was a hechtmaecker (knife handle maker) from Amsterdam,[4] and his mother Neeltij Joosten († before 1658) was the daughter of a merchant in Gouda. Frederick was married on the 29th of August 1661, to Maria van der Way (1632–1711), the daughter of a wealthy Catholic merchant in Amsterdam.[5] From ca. 1648 until his death at the end of July 1706, Frederick de Wit lived and worked in Amsterdam. Frederick and Maria had seven children, but only one Franciscus Xaverius (1666-1727) survived them.[6]

By 1648, during the height of the Dutch Golden Age, De Wit had moved from Gouda to Amsterdam. As early as 1654 he had opened a printing office and shop under the name “De Drie Crabben” (the Three Crabs) which was also the name of his house on the Kalverstraat.[7] In 1655, De Wit changed the name of his shop to the “Witte Pascaert” (the White Chart). Under this name De Wit and his firm became internationally known.[8]

Cartographic work

The first cartographic images that De Wit engraved were a plan of Haarlem that has been dated to 1648,[9] and sometime before 1649 De Wit engraved the city views – city maps for the cities of Rijsel and Doornik that appeared in the richly illustrated Flandria Illustrata by the Flemish historian, Antonius Sanderus.[10]

The first charts engraved by De Wit were published in 1654 under the “De Drie Crabben” address.[11][12] The first map that was both engraved and dated by De Wit was that of Denmark: "REGNI DANIÆ Accuratissima delineatio Perfeckte Kaerte van ‘t CONJNCKRYCK DENEMARCKEN." in 1659. His first world maps, "NOVA TOTIUS TERRARUM ORBIS TABULA AUCTORE F. DE WIT." (approx. 43 x 55 cm) and Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Tabula (a wall map approx. 140 x 190 cm) appeared around 1660.

His Atlas began to appear around 1662 and by 1671 included anywhere from 17 to 151 maps each. In the 1690s he began to use a new title page "Atlas Maior" but continued to use his old title page.[13] His atlas of the Low Countries first published in 1667,[14] was named Nieuw Kaertboeck van de XVII Nederlandse Provinciën and contained 14 to 25 maps.[15] De Wit quickly expanded upon his first small folio atlas which contained mostly maps printed from plates that he had acquired, to an atlas with 27 maps engraved by or for him. By 1671 he was publishing a large folio atlas with as many as 100 maps. Smaller atlases of 17 or 27 or 51 maps could still be purchased and by the mid-1670s an atlas of as many as 151 maps and charts could be purchased from his shop.[16] His atlases cost between 7 and 20 Guilders depending on the number of maps, color and the quality of binding (€47 or $70 to €160 or $240 today).[17] In ca.1675 De Wit released a new nautical atlas. The charts in this atlas replaced the earlier charts from 1664 that are known today in only four bound examples and a few loose copies.[18] De Wit’s new charts were sold in a chart book and as part of his atlases. De Wit published no fewer than 158 land maps and 43 charts on separate folio sheets.[19]

In 1695 De Wit began to publish a town atlas of the Netherlands after he acquired a large number of city plans at the auction of the famous Blaeu publishing firm’s printing plates.

Dating De Wit's atlases is considered difficult because usually no dates were recorded on the maps and their dates of publication extended over many years.

Social standing in Amsterdam

Through his marriage to Maria van der Way in 1661 he obtained, in 1662, the rights of Amsterdam citizenship[20] and was able to become a member of the Guild of Saint Luke in 1664.[21] In 1689 De Wit requested and received a fifteen-year privilege from the States Holland and West-Friesland, that protected his right to publish and sell his maps.[22][23] Then in 1694, he was named a good citizen of the city of Amsterdam.[24]

Maria's stewardship of the firm

After Frederick de Wit's death in 1706 his wife Maria continued the business for four years printing and editing De Wit's maps until 1710. However as De Wit’s son Franciscus was already a prosperous stockfish merchant by this time and had little interest in his father's business he did not take over the publishing house.[25] In 1710 Maria sold the firm at auction.[26]

Legacy

At the auction most of the atlas plates and some of the wall map were sold to Pieter Mortier (1661–1711), a geographer, copper engraver, printer and publisher from Amsterdam.[27] After Mortier’s death, his firm eventually passed to the ownership of his son, Cornelis Mortier and Johannes Covens I who together founded Covens & Mortier on November 20, 1721. Covens & Mortier grew to become one of the largest cartography publishing houses of the 18th century. The 27 chart plates from his 1675 Sea atlas were sold at the 1710 auction, to the Amsterdam print seller Luis Renard, who published them under his own name in 1715, and then sold them to Rennier and Joshua Ottens who continued to publish them until the mid-1700s.

Most special collections libraries, rare map libraries, and private collections hold copies of De Wits atlases and maps. To date over 121 atlases and thousands of loose maps have been identified. Libraries that hold significant numbers are: The Amsterdam University Library, Utrecht University Library, Leiden University Library, Bibliothèque Royale Brussels, The Osher Map Library, Harvard Map Collection, Yale University Beinecke Library, The Library of Congress, Bayersche Staatsbibliothek, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel, Sächsische Landesbibliothek-Staats-und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden, Hungarian National Library, and the collection bequeathed by William Dixson to the State Library of New South Wales.

References

- ^ Isabella H van Eeghen, Frederick de Wit, Amsterdams uitgever, in Drs. A. H. Sijmons’ Jacob Aertsz. Colom’s Kaart van Holland 1681, (Alphen A/D Rijn: Canaletto, 1990) p12

- ^ Van Eeghen, 1990) p12

- ^ Streekarchief Midden-Holland, Gouda: inventarissen: 8. Sociale zorg; vakorganisaties (1)

- ^ Gemeente Amsterdam Stadsarcief: Archief van de Burgerlijke Stand; Doop-, trouw- en begraafboeken van Amsterdam: Book 2476, fish 764 p.50

- ^ Gemeente Amsterdam Stadsarcief: Archief van de Burgerlijke Stand; Doop-, trouw- en begraafboeken van Amsterdam: Bestanddeel:685 p.78

- ^ Gemeente Amsterdam Stadsarcief - Begraafregister

- ^ Van Eeghen, (1990) p.12

- ^ Johann Gottfried Gregorii, Curieuse Gedancken von den vornehmsten und accuratesten alt- und neuen Land-Charten nach ihrem ersten Ursprunge, Erfindung, Auctoribus und Sculptoribus, Gebrauch und Nutzen enworffen ...(Frankfurt, Leipzig, [Erfurt]: Ritschel, 1713) p.75

- ^ Max Eder, Der Annenkirchplatz in Haarlem, in Oud Holland vol 31 (1913) p. 145, p. 148

- ^ G. Caullet, De gegraveerde, onuitgegeven en verloren geraakte teekeningen voor Sanderus’ ‘Flandria illustrata’, in Tijdschrift voor Boek- en Bibliotheekwezen VI, (Amsterdam, Emmanuel de Bom et al,1908), p. 3,53,101.162.

- ^ George Carhart, Dissertation: Frederick de Wit and the first “Concise Reference Atlas”: A reexamination of the Amsterdam map, print and art seller’s life, work and contribution to the distribution of cartographic knowledge during the second half of the 17th and early 18th centuries. (Universität Passau, 02/2011) p.58

- ^ Amsterdam University Library Map Collection, Harvard Map Collection, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

- ^ Carhart, 2011

- ^ Micro film copy of the Oprechte Haerlemse Courant from 14, June 1667: Koninglijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag.

- ^ Ruud Paesie, Het ‘Nieut Kaert-boeck vande XVII Nederlandse Provincie’: New insights into two late 17th-century atlases, in Caert-Thresoor: Tijdschrift voor de Geschiedenis van de Cartografie vol.26 nr.3 (Middelburg: Barent Langenesstichting, 2007) p.77

- ^ I have used the terms “small folio atlas” and “large folio atlas” here so that the use of large and small can be seen to refer to the number of maps and not the size of atlas - pocket v table atlas.

- ^ “Value of the Guilder” <http://www.iisg.nl>.

- ^ Carhart, 2011

- ^ Carhart, 2011

- ^ Gemeente Amsterdam Stadsarcief - Poorterboek Nr 2 - p.181

- ^ Amsterdam Archive, Guild of St. Lucas, number. 366/65

- ^ Frederik D.O. Obreen, Archief voor Nederlandsche Kunstgeschiedenis:Verzameling van Neerendeels Onutgegeven Berichten en Mededeelinge, (Rotterdam: W.J. Hengel, 1888–1890.) Vol. 7

- ^ National archive Den Haag, inventory of the archives of the States Holland and West-Friesland 1572-1795: Archive: 3.01.04.01, # 1640

- ^ Van Eeghen,(1990)

- ^ Carhart (2011)

- ^ Peter van der Krogt, Advertenties voor kaarten, atlassen, globes e.d. in Amsterdamse kranten 1621-1811, (Utrecht: HES, 1985) p. 75-76.

- ^ Marco van Egmond, Covens & Mortier: A Map Publishing House in Amsterdam 1685-1866, (Houten, Netherlands: HES & DE GRAF, 2009) p.125

Maps

-

Nova et accurata totius Europæ descriptio (1700)

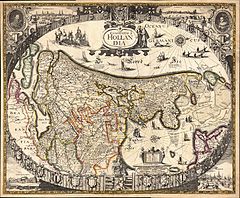

-

Anonymous map of Hollandia (1630) reprinted ca 1660, by Frederik de Wit.

-

Map by Frederik de Wit, 1660.

-

Celestial Map (1670) by Frederik de Wit

-

America by Frederick de Wit, 1670-1690.

-

Afrika by Frederick de Wit, 1688.

-

Asia by Frederick de Wit.

-

Europe (1672).

-

Coast of the North Sea (1675) by Frederik de Wit

-

Flandriæ (1689) by Frederik de Wit

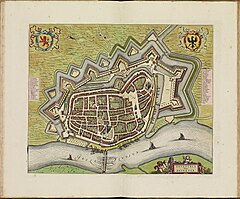

-

Deventer City Map (1698) by Frederik de Wit

-

Livoniæ and Curlandiæ (1710) by Frederik de Wit/Pieter Mortier

External links

- Amsterdam University, 32 maps by de Wit

- Amsterdam University, Townmaps from the Netherlands

- Amsterdam University, Townmaps of European cities

- Maps of 18th century Livoniæ - National Library of Estonia (Digital Collection)

- Map of America (approx 1670) - David Rumsey Historical Map Collection

- Atlas of Cities - Royal Library of the Netherlands

- Promosite on the facsimile edition of de Wit's Townatlas 2012

- "A Drawing (with a Western Perspective) of the East Indies from the Promontory of Good Hope to Cape Comorin" was designed by De Wit in ca.1675