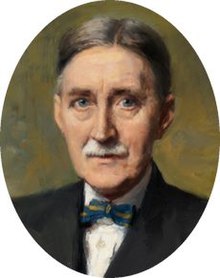

George Dyson (composer)

Sir George Dyson KCVO (28 May 1883 – 28 September 1964) was an English musician and composer. After studying at the Royal College of Music (RCM) in London, and army service in the First World War, he was a schoolmaster and college lecturer. In 1938 he became director of the RCM, the first of its alumni to do so. As director he instituted financial and organisational reforms and steered the college through the difficult days of the Second World War.

As a composer Dyson wrote in a traditional idiom, reflecting the influence of his teachers at the RCM, Hubert Parry and Charles Villiers Stanford. His works were well known during his lifetime but underwent a period of neglect before being revived in the late 20th century.

Life and career

[edit]Early years

[edit]Dyson was born in Halifax, Yorkshire, the eldest of the three children of John William Dyson, a blacksmith, and his wife, Alice, née Greenwood, a weaver.[1] Dyson senior was also organist and choirmaster at a local church, and both parents were members of amateur choirs. They encouraged their son's musical talent, and at the age of 13 he was appointed as a church organist. Three years later he secured an FRCO (Fellowship of the Royal College of Organists), and in 1900 he won an open scholarship to the Royal College of Music (RCM) where he studied composition with Sir Charles Villiers Stanford.[1] He supported himself during his years studying at the RCM by working as assistant organist at St Alfege Church, Greenwich.[2]

He won the Arthur Sullivan prize for composition[3] while still an RCM student, and in 1904 was awarded a Mendelssohn Scholarship,[4] which enabled him to spend three years in Italy, Austria and Germany. He met leading musicians including Richard Strauss, whose style is believed to have influenced Dyson's early compositions.[5] His symphonic poem Siena (1907) was considered by The Times to stand out from many works by other young composers,[6] but the score has not survived.[5][7]

When he returned to Britain in 1907 Dyson was appointed director of music at the Royal Naval College, Osborne, on the recommendation of Sir Hubert Parry, director of the RCM.[5] From there he moved to Marlborough College in 1911.[4]

On the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 Dyson joined the Royal Fusiliers, becoming grenadier officer of the 99th infantry brigade. In that role he wrote a training pamphlet on grenade warfare for which he became well known. In 1916, incapacitated by shell-shock, he was invalided back to England. Parry recorded in his diary how shaken he was when he saw Dyson, "a shadow of his former self".[8]

In November 1917 Dyson married Mildred Lucy Atkey (1880–1975), daughter of a London solicitor. They had a son, Freeman, who became a noted theoretical physicist and mathematician, and a daughter, Alice. In 1917 Dyson received the degree of DMus from the University of Oxford.[1]

After a long convalescence Dyson was commissioned as a major in the newly formed Royal Air Force (RAF), serving until 1920.[4] In this capacity, organising RAF bands, he completed the short score of Henry Walford Davies's RAF March Past, adding a slow middle section and fully scoring the whole piece.[1]

Schoolmaster and professor

[edit]In 1920 Dyson's composing career advanced when his Three Rhapsodies for string quartet were chosen for publication under the Carnegie Trust's publication scheme.[8] In 1921 he took up the posts of music master at Wellington College and professor of composition at the RCM. In 1924, while remaining at the RCM he switched schools, moving to Winchester College. His biographer Lewis Foreman comments that it was during his dual tenure at the RCM and Winchester that "the various strands of his mature career as a composer developed".[1]

In addition to teaching at the RCM and Winchester and directing the school's music, Dyson was conductor of an adult choral society, and a visiting lecturer at Liverpool and Glasgow universities;[4] composing had to be fitted into what spare time he had.[8] Works from this period include the cantata In Honour of the City (1928), described by The Musical Times as "a virile fantasia for chorus and orchestra [which] illustrates memorably the composer's talent for diatonic melody of impressive eloquence, his predilection for enharmonic modulation contrived with apposite ingenuity, and his accomplished handling of orchestral subtleties."[9] Foreman writes that the cantata was so successful that Dyson soon produced a more ambitious piece, The Canterbury Pilgrims (1931) "a succession of evocative and colourful Chaucerian portraits … and probably his most famous score".[1]

British choral festivals commissioned new works from Dyson. For the Three Choirs Festival he composed St Paul's Voyage to Melita (1933) and Nebuchadnezzar (1935) and for Leeds, The Blacksmiths (1934). Purely orchestral works included a Symphony in G (1937), which The Times praised for originality, underivative nature and avoidance of "the freakishly obscure or the pompously grandiose".[10]

From the early 1930s Dyson and others had been concerned about the future of amateur music making in Britain, which was under increasing pressure from the Great Depression and what Dyson called "the invasions of mechanical music" – the gramophone and the radio.[11] With the aid of the Carnegie Trust Dyson co-founded the National Federation of Music Societies in 1935 as an umbrella organisation and financial bulwark for music groups and performing societies.[11]

RCM director and later years

[edit]

In 1938 Dyson was appointed director of the RCM on the retirement of Sir Hugh Allen; he took great pride in being the first former student of the RCM to become its director.[8] He secured funding for the college from the University Grants Committee, and set up a pension scheme for the staff. He instituted an overhaul of the college's facilities, from rehearsal space down to lavatories, to provide a better working environment for the students.[12] He also modernised the curriculum and examination system of the college.[13] He held the strong view that with first-rate performances of music now easily and regularly available on radio and record, people now coming into the musical profession needed to attain the highest standards if they were to compete.[14] His emphasis on technical excellence led to criticism; The Times said that he "reversed the humanistic trend that had been the ideal of the college".[15]

When the Second World War began in 1939 many educational and other organisations were evacuated from London to avoid the expected bombing. Dyson was adamant that the RCM should remain in its home in South Kensington.[16] His decision had important consequences beyond the college, as other institutions followed suit, with the result that continuity of training was possible and standards were maintained.[15] At the RCM, Malcolm Sargent took charge of the college orchestra, and Karl Geiringer, displaced by the Nazis from the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, joined the faculty.[17]

After the war, Dyson had to deal with a surge in demand for places at the college: students who had interrupted their studies to join the armed forces and the post-war generation of new applicants swelled the numbers of applicants, and Dyson and his board were obliged to make the requirements for entry more stringent.[18] His emphasis on practical musicianship led him to cull the college's library and archives, disposing of many old books and manuscripts, to the outrage of some colleagues.[19]

Dyson's encouragement of talent sometimes showed itself in a willingness to depart from normal practice when he felt it necessary. Although Colin Davis, as a clarinet student, was not allowed to take part in the conducting class because his pianistic skills were judged inadequate,[20] Malcolm Arnold fared better: even though he decamped from the college, Dyson encouraged him to return and smoothed his path in doing so;[21] for Julian Bream Dyson made special arrangements to enable him to pursue his guitar studies, not hitherto part of the college's curriculum.[22]

Dyson received a knighthood in the 1941 New Years Honours List and was appointed Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (KCVO) in 1953. He held honorary degrees from the universities of Aberdeen and Leeds and honorary fellowships of the Royal Academy of Music and Imperial College London.[4]

In 1952 Dyson retired from the RCM. He moved to Winchester, and enjoyed what Foreman describes as "a remarkable Indian summer" of composition, although by this time his music seemed old-fashioned to some listeners. His late works were published and performed, but did not, according to Foreman, "have quite the immediate following" of the music from earlier in his career.[1]

Dyson died at his home in Winchester on 28 September 1964, aged 81.[23]

Music

[edit]Dyson said of himself as a composer, "My reputation is that of a good technician … not markedly original. I am familiar with modern idioms but they are outside the vocabulary of what I want to say".[15] The music critic of The Times remarked that Dyson's works had a certain ambiguity, "due probably to the fact that great musical skill was allied, exceptionally, with an extrovert temperament." The same writer observed that although everything Dyson wrote was well made, he never developed a personal idiom, "nor engendered much emotional sap in his larger works".[15]

Dyson's biographer Paul Spicer writes that of the composer's works only The Canterbury Pilgrims and two sets of evening canticles in D and F are performed with any frequency.[24] Dyson himself chose to include the following works in his Who's Who entry: In Honour of the City, 1928; The Canterbury Pilgrims, 1931; St Paul's Voyage, 1933; The Blacksmiths, 1934; Nebuchadnezzar, 1935; Symphony, 1937; Quo Vadis, 1939; Violin Concerto, 1942; Concerto da Camera and Concerto da Chiesa for Strings, 1949; Concerto Leggiero for Piano and Strings, 1951; Sweet Thames Run Softly, 1954; Agincourt, 1955; Hierusalem, 1956; Let's go a-Maying, 1958; and A Christmas Garland, 1959.[4]

In addition to those mentioned by the composer, the Dyson Trust lists the following compositions as available as at 2017: A Spring Garland, Children's Suite for orchestra, Evening Service in C Minor, Evening Service in D, Morning Service in D, Prelude, Fantasy and Chaconne for cello and orchestra, Te Deum Laudamus, and Three Rhapsodies for string quartet.[25] The Trust has published a full list of works, totalling nine orchestral works, seven chamber works, thirteen pieces or sets of pieces for piano, four solo organ pieces, twenty works for chorus and orchestra, seventy-nine works for chorus with piano, or organ or unaccompanied, five hymns, six songs, and thirteen lost or destroyed works from the composer's early career.[26] In 2014, to mark the 50th anniversary of Dyson's death, Ben Costello produced an arrangement of In Honour of the City for two pianos and percussion.

Legacy

[edit]Foreman writes that a revival of Dyson's music was started by Christopher Palmer, who published George Dyson: a Centenary Appreciation (1984) and Dyson's Delight (1989), a selection of Dyson's uncollected articles and talks on music, and also promoted the first modern recordings of Dyson's music.[1] The Sir George Dyson Trust was established in 1998, with the declared aim of advancing public education in the understanding and appreciation of Dyson's music, and making available his manuscripts, writings, scores, drafts and memoranda for the encouragement of the study of his work.[27] Late Freeman Dyson was also a champion of his father's music.[28]

Books by Dyson

[edit]- Grenade Warfare: Notes on the Training and Organisation of Grenadiers (1915)

- The New Music (1924)

- The Progress of Music (1932)

- Fiddling While Rome Burns (1954)

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Foreman, Lewis. "Dyson, Sir George (1883–1964)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved 20 November 2017 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Spicer, p. 15

- ^ Spicer, p. 35

- ^ a b c d e f "Dyson, Sir George", Who Was Who, online edition, Oxford University Press, 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2017 (subscription required)

- ^ a b c Foreman, Lewis. "Dyson, Sir George", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 20 November 2017. (subscription required)

- ^ "Music", The Times, 21 May 1909, p. 1

- ^ France, John (29 July 2008). "British Classical Music: The Land of Lost Content: George Dyson : Siena Overture". British Classical Music. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d Foreman, Lewis. Notes to Naxos CD 8.557720 (2004)

- ^ Hull, Robert H. "George Dyson", The Musical Times, September 1933, pp. 800–801 (subscription required)

- ^ "Queen's Hall: Dr Dyson's New Symphony", The Times, 17 December 1937, p. 14

- ^ a b Dyson, George. "Towards National Co-operation: An Outline and a Policy", The Musical Times, February 1936, pp. 121–125 (subscription required)

- ^ Spicer, p. 238

- ^ Spicer, p. 240

- ^ Spicer, p. 242

- ^ a b c d "Obituary: Sir George Dyson", The Times, 30 September 1964, p. 17

- ^ Spicer, p. 245

- ^ Spicer, p. 247

- ^ Spicer, p. 272

- ^ Spicer, pp. 276–277

- ^ Blyth, p. 8

- ^ Spicer, p. 232

- ^ Spicer, pp. 295–296

- ^ Spicer, p. 394

- ^ Spicer, p. 1

- ^ "Works" Archived 1 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Sir George Dyson Trust. Retrieved 22 November 2017

- ^ "Sir George Dyson: List of Works" Archived 31 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Sir George Dyson Trust. Retrieved 22 November 2017

- ^ "Welcome", Sir George Tyson Trust. Retrieved 22 November 2017

- ^ 'Freeman Dyson, Math Genius Turned Visionary Technologist, Dies at 96' in the New York Times, 28 February 2020

Sources

[edit]- Blyth, Alan (1972). Colin Davis. London: Ian Allan. OCLC 675416.

- Spicer, Paul (2014). Sir George Dyson: His Life and Music. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-903-3.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to George Dyson (composer) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to George Dyson (composer) at Wikimedia Commons

- Sir George Dyson Trust

- Free scores by George Dyson in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Performance of Dyson Fantasy for cello and orchestra on YouTube by Julian Lloyd Webber and the Academy of St Martin in the Fields conducted by Neville Marriner

- Audio track of Dyson Magnificat in F available from Cardiff Cathedral Choir.org

- 1883 births

- 1964 deaths

- Musicians from Halifax, West Yorkshire

- 20th-century English composers

- Alumni of the Royal College of Music

- Academics of the Royal College of Music

- Directors of the Royal College of Music

- Instructors of the Royal Naval College, Osborne

- Knights Commander of the Royal Victorian Order

- Knights Bachelor

- Composers awarded knighthoods

- Freeman Dyson

- Pupils of Charles Villiers Stanford

- Royal Air Force personnel of World War I

- Royal Fusiliers officers

- Royal Air Force officers

- Royal Air Force musicians

- British Army personnel of World War I

- British military musicians

- Presidents of the Independent Society of Musicians