Gorton government

Gorton government | |

|---|---|

| |

| In office | |

| 10 January 1968 – 10 March 1971 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Prime Minister | John Gorton |

| Deputy | John McEwen (to Feb. 1971) Doug Anthony (from Feb. 1971) |

| Parties | Liberal Country |

| Origin | Gorton wins 1968 Liberal leadership election |

| Demise | Gorton's resignation |

| Predecessor | McEwen government |

| Successor | McMahon government |

The Gorton government was the federal executive government of Australia led by Prime Minister John Gorton. It was made up of members of a Liberal-Country Party coalition in the Australian Parliament from January 1968 to March 1971.

Background

[edit]The Liberal Party of Australia-Country Party of Australia Coalition, led by Prime Minister Harold Holt, won the November 1966 election against the Australian Labor Party opposition led by Arthur Calwell. The Coalition won a substantial majority – the Liberals winning 61 seats and the Country Party 21 – with the Labor Party winning 41 and 1 Independent in the Australian House of Representatives (representing the largest parliamentary majority in 65 years).[1] The Coalition had governed since 1949, and the Liberal Party had replaced the retiring Robert Menzies with Holt in January 1966.[2]

Following the 1966 election, Gough Whitlam replaced Arthur Calwell as Leader of the Opposition. On 17 December 1967, Holt disappeared in heavy surf while swimming off Cheviot Beach, near Melbourne, becoming the third Australian Prime Minister to die in office.[2] Country Party leader John McEwen served as prime minister from 19 December 1967 to 10 January 1968, pending the election of a new leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.[3] McEwen ruled out maintaining the Coalition if deputy Liberal leader William McMahon became prime minister. John McEwen, leader of the Country Party, had been sworn in as caretaker prime minister until a new Liberal leader was elected. McEwen had ruled out further participation in the Coalition if William McMahon, the deputy Liberal leader, became prime minister. The Minister for External Affairs, Paul Hasluck, Minister for Labour and National Service Leslie Bury and Minister for Immigration Billy Snedden, also nominated for election to the leadership. Gorton won the leadership election with a small majority and resigned from the Senate to stand for election to Higgins, the House of Represensatives seat formerly held by Harold Holt, which he achieved on 24 February 1968.[4]

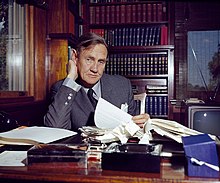

John Gorton

[edit]

John Gorton had studied Politics, History and Economics at Oxford University and served as pilot in the Royal Australian Airforce during the Second World War. His aircraft crashed during the defence of Singapore, and Gorton was badly injured. His face remained forever scarred, but Gorton managed to escape, only for his ship to be torpedoed at Batavia – where, by clinging to an improvised raft, he again escaped death and was able to return to Australia for medical treatment and to serve in the air defence of Northern Australian and New Guinea.

Gorton obtained a seat as a Liberal Senator at the 1949 Election and was promoted by Robert Menzies to become Minister for the Navy 9 years later and he went on to serve in various portfolios in both the Menzies and Holt governments. In 1967, Prime Minister Harold Holt appointed Gorton as Leader of the Government in the Senate. Soon after, Holt drowned and Gorton decided to run for the office of prime minister, though he lacked a House of Representatives seat. Liberal Patriarch Robert Menzies favoured Paul Hasluck. Future Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser firmly backed Gorton. The leadership ballot was fervently contested.[5] In his 2010 Memoir, Lazarus Rising, long serving Liberal Prime Minister John Howard wrote that Gorton was the first person to win the leadership of an Australian party "through the force of his television appearances". In the lead up to the leadership vote, Gorton was little known but appeared on television, where, wrote Howard, he gave direct answers and his "relaxed, laconic manner, coupled with his crumpled war-hero face, really appealed to viewers".[6] Political commentator Alan Reid said:[5]

Gorton set out deliberately to give the impression of a fairly ordinary, decent Australian, with a sense of humour and intelligence and the capacity to make decisions

Gorton's leadership style

[edit]

Gorton, a former World War II RAAF pilot, with a battle scarred face, said he was "Australian to the bootheels" and had a personal style which often affronted some conservatives. Gorton told the media that he saw the role of prime minister not as being like the chairman of committee, who should submit to majority votes of Cabinet, but rather that a prime minister should put his position to Cabinet as what ought to be done, and "if he believes strongly enough that it ought to be done, then it must be done". Accordingly, he visited President Johnson of the United States in 1968 without taking any advisors from External Affairs and interfered heavily in the preparation of Treasurer William McMahon's budgets. According to political historian Brian Carroll:[5]

[Gorton's] style was Presidential rather than Prime Ministerial. He was not particularly convinced of unlimited foreign investment. His ideas on defence were those of "Fortress Australia". And he seemed to be more of a centralist than a federalist.

Domestic policy

[edit]Social policy

[edit]

The Gorton government increased funding for the arts, setting up the Australian Council for the Arts, the Australian Film Development Corporation and the National Film and Television Training School. It passed legislation establishing equal pay for men and women and increased pensions, allowances and education scholarships, as well as providing free health care to 250,000 of the nation's poor (but not universal health care).[7]

The government also passed the Copyright Act 1968, the first national copyright legislation of Australian origin; previously Australia had simply used the British Copyright Act 1911. The new act, which came into effect on 1 May 1969, "completely overhauled the copyright law and introduced new provisions", and remains in force although some amendments have been made. The bill had been first introduced by the Holt government in 1967, based on the Spicer Committee's report of 1959.[8]

The Australian Metric Conversion Act 1970 created the Metric Conversion Board to facilitate conversion to the metric system. With a few exceptions, metrication was completed by the end of 1974.[9]

Energy

[edit]Gorton had been an advocate of nuclear power since the 1950s. In his policy speech at the 1969 election, he pledged to "take Australia into the atomic age".[10] Later that year, he secured cabinet approval for the construction of a nuclear reactor in the Jervis Bay Territory, which would have been Australia's first nuclear power plant (though not the first nuclear reactor). Tenders were issued for the plant's construction and some construction was begun, but the project was cancelled in June 1971 after McMahon became prime minister.[11] A 2002 documentary, Fortress Australia, claimed that the real motive for the creation of the plant was to allow Australia to build its own nuclear weapons.[12]

Centralism

[edit]

Gorton had earned a reputation as a centralist during his time as an active Education Minister – a responsibility formerly considered the preserve of state governments. As prime minister, it was his decision to seek control of offshore mineral resources for the Commonwealth which cemented this reputation.

Other

[edit]In December 1970 Gorton announced that the previous 50-year public access rule for classified cabinet documents would be reduced to 30 years.[13]

Foreign policy

[edit]

Gorton maintained good relations with the United States and Britain, but pursued closer ties with Asia. Gorton's government kept Australia in the Vietnam War but stopped replacing troops at the end of 1970.[7]

Defence

[edit]Gorton initially considered support for a "Fortress Australia" defence policy that would involve building Australia's independent industrial and military capacity. The Gorton government opposed expansion of Australia's commitment to the Vietnam War. It also faced the withdrawal of British forces from Malaysia and Singapore and after extended consideration of the development, committed to retaining forces in Malaya – but stressed that they could not be used to maintain civil law and order.[5]

Gorton appointed his supporter, Malcolm Fraser, as Defence Minister – but the relationship between the pair deteriorated and Fraser resigned in 1971, precipitating a leadership crisis.

1969 election and leadership tensions

[edit]

The Gorton government experienced a decline in voter support at the 1969 election. State Liberal leaders saw his policies as too Centralist, while other Liberals did not like his personal behaviour. Prior to the 1969 election, Gorton had largely retained the Holt-McEwen ministry he inherited. After the 1969 election, Malcolm Fraser replaced the retired Allen Fairhall as Minister for Defence, Don Chipp, Senator Bob Cotton, Senator Tom Drake-Brockman (Country Party), Mac Holten (Country Party), Tom Hughes, James Killen and Andrew Peacock were promoted into the ministry.

In his 2010 memoir, John Howard wrote of the 1969 Election that Whitlam outperformed Gorton during the Election campaign. In Howard's assessment, Gorton had an "appealing personality, direct style and was extremely intelligent" but it was his "lack of general discipline over such things as punctuality that did him damage". After the election, Gorton faced leadership challenges from David Fairbairn, a senior minister from New South Wales and from Deputy Leader Bill McMahon. Of the period Howard wrote: "By this time John McEwen had dropped his veto of McMahon, a sure sign that the Country Party had grown uneasy with Gorton's governing style.[6]

Gorton resignation

[edit]

Tensions within the government came to a point when David Fairbairn, the Minister for National Development, announced a refusal to serve in a Gorton Cabinet. Fairbairn and Treasurer William McMahon, unsuccessfully challenged Gorton for leadership of the Liberal Party. McMahon was removed from Treasury to External Affairs and Leslie Bury was appointed Treasurer.[7]

The government performed poorly in the 1970 half senate election adding to pressures on Gorton's leadership. Defence minister Malcolm Fraser developed an uneasy relationship with Gorton and in early 1971, Fraser accused Gorton of being disloyal to him in a conflict with Army officials over progress in South Vietnam.[14] Fraser was engaged in a struggle over authority with service chiefs, when in 1971, journalist Alan Ramsay published an article quoting Defence Chief Sir Thomas Daly as having described Fraser as extremely disloyal to the army and to its junior minister, Andrew Peacock. Ramsay had conferred with Gorton prior to publishing the article, but Gorton had not repudiated its contents. Fraser seized upon the report, resigned and accused Gorton of intolerable disloyalty.[5] On 9 March Fraser told Parliament that Gorton was "not fit to hold the great office of Prime Minister".[7] Fraser accused Gorton of obstinacy and a dangerous reluctance to take advice from Cabinet or the Public Service.[5]

John Howard wrote of Gorton-Fraser relationship that Fraser had been one of Gorton's key backers in 1968, when Gorton secured the leadership after the death of Holt, yet "it was Fraser quitting the Government, followed by a searing resignation speech, which triggered the events producing Gorton's removal".[6]

On 10 March, the Liberal party room moved to debate and vote on a motion of confidence in Gorton as party leader, resulting in a 33–33 tie. Under Liberal rules of the time, this meant Gorton retained the leadership. However, Gorton declared that a tie vote was not a true vote of confidence, and resigned the leadership. Former treasurer, William McMahon, replaced Gorton as prime minister.[15]

Aftermath

[edit]Gorton was elected deputy leader and was appointed as Minister for Defence by Prime Minister William McMahon. Soon after however, Gorton wrote a series of articles for the Sunday Australian entitled "I did it my way", enabling McMahon to ask for and receive Gorton's resignation from Cabinet and as Deputy Leader. Gorton became an internal critic of the party.

John Howard wrote in 2010 that the "personal animosity which flowed from the manner of Gorton's removal as prime minister was the most intense that I have ever seen in politics. Gorton never forgave Fraser for his perceived betrayal. In March 1975, when Malcolm Fraser was elected Leader of the Liberal Party, Gorton, who had voted for Snedden, immediately the result of the ballot was announced, walked out of the party room, slamming the door behind him, and never returned to the room again." Gorton contested the 1975 Election an independent candidate for the Senate.[6]

McMahon's premiership ended when Gough Whitlam led the Australian Labor Party out of its 23-year period in Opposition at the 1972 Election.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Electionsnaa.gov.au Archived 26 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Holt in officenaa.gov.au Archived 15 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Prime Ministers. McEwennaa.gov.au Archived 24 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Before officenaa.gov.au Archived 15 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f Brian Carroll; From Barton to Fraser; Cassell Australia; 1978

- ^ a b c d John Howard; Lazarus Rising: A Personal and Political Autobiography; Harper Collins; 2010.

- ^ a b c d In officenaa.gov.au Archived 26 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Adrian Sterling (2011). "The Copyright Act 1968: its passing and achievements" (PDF). In Brian Fitzgerald; Benedict Atkinson (eds.). Copyright Future, Copyright Freedom: Marking the 40th Anniversary of the Commencement of Australia's Copyright Act 1968. Sydney University Press.

- ^ "History of Measurement in Australia". National Measurement Institute. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ "Australian Federal Election Speeches: John Gorton 1969". Museum of Australian Democracy. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ "John Gorton". Museum of Australian Democracy. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ "How a scared little country became a nuclear wannabe". The Sydney Morning Herald. 17 August 2002. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ "Embargo eased on secret papers". The Canberra Times. 31 December 1970.

- ^ Before officenaa.gov.au Archived 29 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ In officenaa.gov.au Archived 15 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine