Great Divergence (inequality)

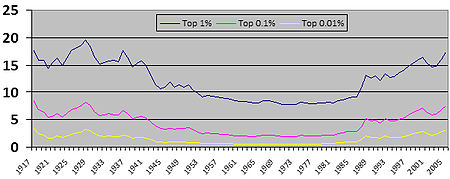

The Great Divergence is a term given to a period, starting in the late 1970s, during which income differences increased in the US and, to a lesser extent, in other countries. The term originated with Nobel laureate, Princeton economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman,[1] and is a reference to the "Great Compression", an earlier era in the 1930s and the 1940s when incomes became more equal in the US and elsewhere.[2]

A 2017 report by the Congressional Budget Office on the distribution of income in the US, from 1979 to 2007, found that after federal taxes and income transfers, the top earning 1% of households gained about 275% and that the bottom 20% grew by only 41%.[5] As of 2006, the US had one of the highest levels of income inequality, as measured through the Gini index, among similar developed or First World countries.[6]

Scholars and others differ as the causes and significance of the divergence,[7][8] which, in 2011, helped ignite the "Occupy" protest movement. While education and increased demand for skilled labor is often cited as a cause of increased inequality,[9] especially among conservatives, many social scientists[10] point to conservative politics, neoliberal economic and social policies[11][12] and public policy as an important cause of inequality; others believe its causes are not well understood.[13] Inequality has been described both as irrelevant in the face of economic opportunity (or social mobility) in America and as a cause of the decline in that opportunity.[14][15]

Journalist James Surowiecki points out the changes in the US economy in the last 50 years and how important low wages are now to big employers in the US.

In 1960, the country's biggest employer, General Motors, was also its most profitable company and one of its best-paying. It had high profit margins and real pricing power, even as it was paying its workers union wages. And it was not alone: firms like Ford, Standard Oil, and Bethlehem Steel employed huge numbers of well-paid workers while earning big profits. Today, the country's biggest employers are retailers and fast-food chains, almost all of which have built their businesses on low pay—they've striven to keep wages down and unions out—and low prices.[16]

While these retailers and fast-food chains are profitable, their profit margins are not large, which limits their ability to follow the lead of successful companies in high-growth industries that pay relatively generous salaries, such as Apple Inc..

The combined profits of all the major retailers, restaurant chains, and supermarkets in the Fortune 50] are smaller than the profits of Apple alone. Yet Apple employs just 76,000 people, while the retailers, supermarkets, and restaurant chains employ 5.6 million.[16]

The International Labour Organisation's annual "World of Work Report", predicted that the potential for social unrest in the European Union is the highest in the world.[17]

See also

- Economic history of the United States

- Economic inequality

- Economic stagnation

- Neoliberalism

- Socio-economic mobility in the United States

- The End of Work

- Wealth inequality in the United States

References

- ^ Krugman, Paul, The Conscience of a Liberal, W W Norton & Company, 2007, pp. 124–28

- ^ The Great Divergence. By Timothy Noah

- ^ Saez, E. & Piketty, T. (2003). Income inequality in the United States: 1913–1998. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 1–39.

- ^ "Saez, E. (October, 2007). Table A1: Top fractiles income shares (excluding capital gains) in the US, 1913–2005". Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- ^ Congressional Budget Office: Trends in the Distribution of Household Income Between 1979 and 2007. October 2011. Figure 3.

- ^ Weeks, J. (2007). Inequality Trends in Some Developed OECD countries. In J. K. S. & J. Baudot (Ed.), Flat World, Big Gaps (159–74). New York: ZED Books (published in association with the UN).

- ^ Krugman, Paul. "The Rich, the Right, and the Facts: Deconstructing the Income Distribution Debate" prospect.org, 19 December 2001

- ^ Sowell, Thomas. "Perennial Economic Fallacies," Jewish World Review 07 February 2000, URL accessed 3 November 2011.

- ^ "CIA. (June 14, 2007). United States: Economy. World Factbook". Retrieved 20 June 2007.

- ^ such as economists Paul Krugman and Timothy Smeeding and political scientists Larry Bartels and Nathan Kelly

- ^ Stephen Haymes, Maria Vidal de Haymes and Reuben Miller (eds), The Routledge Handbook of Poverty in the United States, (London: Routledge, 2015), ISBN 0415673445, p. 7.

- ^ David M. Kotz, The Rise and Fall of Neoliberal Capitalism, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2015), ISBN 0674725654. p. 43

- ^ Congressional Budget Office: Trends in the Distribution of Household Income Between 1979 and 2007. October 2011.

- ^ Here is the source for the "Great Gatsby Curve" in the Alan Krueger speech at the Center for American Progress on 12 January

- ^ White House: Here's Why You Have To Care About Inequality Timothy Noah | tnr.com| 13 January 2012

- ^ a b Surowiecki, James (12 August 2013). "The Pay Is Too Damn Low". The New Yorker.

- ^ Evans, Robert (3 June 2013). "EU potential for social unrest is world's highest: ILO". International Labour Organization. Reuters.