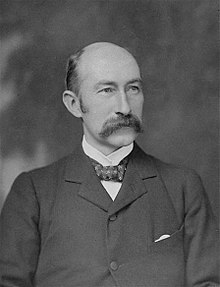

H. B. Higgins

Henry Bournes Higgins | |

|---|---|

| |

| Justice of the High Court of Australia | |

| In office 13 October 1906 – 13 January 1929 | |

| Nominated by | Alfred Deakin |

| Preceded by | none |

| Succeeded by | Sir Owen Dixon |

| Member of the Australian Parliament for North Melbourne | |

| In office 30 March 1901 – 12 December 1906 | |

| Preceded by | Seat Created |

| Succeeded by | Seat Abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 30 June 1851 Newtownards, Mayo, Ireland |

| Died | 13 January 1929 (aged 77) |

- For the fictional character Henry Higgins, see Pygmalion or My Fair Lady.

Henry Bournes Higgins (30 June 1851 – 13 January 1929), Australian politician and judge, always known in his lifetime as H. B. Higgins, was a highly influential figure in Australian politics and law.

Early life and education

He was born in Newtownards, County Down, Ireland, the son of The Rev. John Higgins,[1] a Methodist minister, and Anne Bournes, daughter of Henry Bournes of Crossmolina. Ina Higgins, an early feminist, was his sister and Nettie Palmer, poet, essayist and literary critic, was a niece. The Rev. Higgins and his family emigrated to Australia in 1870.

H. B. Higgins was educated at Wesley College in central Dublin, Ireland, and at the University of Melbourne, where he graduated in law. He practised at the Melbourne bar from 1876, eventually becoming one of the city's leading barristers (a QC in 1903) and a wealthy man. He was active in liberal, radical, and Irish nationalist politics, as well as in many civic organisations. He was also a noted classical scholar.

Career

Political career

In 1894, Higgins was elected to the Victorian Legislative Assembly as MLA for Geelong. He was a supporter of George Turner's liberal government, but frequently criticised it from a left-wing point of view. He supported advanced liberal positions, such as greater protection for workers, government investment in industry, and votes for women. In 1897, he was elected as one of Victoria's delegates to the convention which drew up the Australian Constitution. At the convention, he successfully argued that the constitution should contain a guarantee of religious freedom, and also a provision giving the federal government the power to make laws relating to the conciliation and arbitration of industrial disputes.

Despite these successes, he opposed the draft constitution produced by the convention as too conservative, and campaigned unsuccessfully to have it defeated at the 1899 Australian constitutional referendum. This alienated him most of his liberal colleagues, and also from the influential Melbourne newspaper, The Age. Higgins also opposed Australian involvement in the Second Boer War, a very unpopular stand at the time, and as a result, he lost his seat at the 1900 Victorian election.

In 1901, when federation under the new constitution came into effect, Higgins was elected to the first House of Representatives for the working-class electorate of Northern Melbourne. He stood as a Protectionist, but the Labor Party did not oppose him, regarding him as a supporter of the labour movement. The Labor Party's confidence in him was shown in 1904, when Chris Watson formed the first federal Labor government. Since the party did not have a suitably qualified lawyer, Watson offered the post of Attorney-General to Higgins. He is the only person to have held office in a federal Labor government without being a member of the Labor Party.

Judicial career

Higgins was an awkward colleague for the Protectionist leadership, and in 1906 Deakin appointed him as a Justice of the High Court of Australia as a means of getting him out of politics, although he was undoubtedly qualified for the post. In 1907, he was also appointed President of the newly created Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration, created to arbitrate disputes between trades unions and employers, something Higgins had long advocated. In this role, he continued to support the labour movement, although he was strongly opposed to militant unions who abused the strike weapon and ignored his rulings.

Higgins was one of only eight justices of the High Court to have served in the Parliament of Australia prior to his appointment to the Court; the others were Edmund Barton, Richard O'Connor, Isaac Isaacs, Edward McTiernan, John Latham, Garfield Barwick, and Lionel Murphy. He was also one of two justices to have served in the Parliament of Victoria, along with Isaac Isaacs.

In 1907, Higgins delivered a judgement which became famous in Australian history, known as the "Harvester Judgement". The case involved one of Australia's largest employers, Hugh McKay, a manufacturer of agricultural machinery. Higgins ruled that McKay was obliged to pay his employees a wage that guaranteed them a standard of living that was reasonable for "a human being in a civilised community," regardless of his capacity to pay. This gave rise to the legal requirement for a basic wage, which dominated Australian economic life for the next 80 years.

During World War I, Higgins increasingly came into conflict with the Nationalist Prime Minister Billy Hughes, whom he saw as using the wartime emergency to erode civil liberties. Although Higgins initially supported the war, he opposed the extension of government power that came with it, and also opposed Hughes' attempt to introduce conscription for the war. In 1916, his only son Mervyn was killed in action in Egypt, a tragedy which made Higgins turn increasingly against the war.

Later life

The postwar years saw a series of bitter industrial confrontations, some of them fomented by militant unions influenced by the Industrial Workers of the World or the Communist Party of Australia. Higgins defended the principles of arbitration against both the Hughes Government and militant unions, although he found this his increasingly difficult. Postwar governments appointed conservative justices to the High Court, leaving Higgins increasingly more isolated. In 1920, he resigned from the Arbitration Court in frustration, but remained on the High Court bench until his death in 1929. In 1922, he published A New Province for Law and Order, a defence of his views and record on arbitration.

Personal life

After his son Mervyn's death, Higgins effectively adopted his nephew Esmonde Higgins and his niece Nettie Palmer, paying for their education at universities in Europe. He was pained by Esmonde's conversion to Communism in 1920 and his rejection of the liberal values associated with the Higgins name.

Aside from politics, he was president of the Carlton Football Club in 1904.

Legacy

Higgins was remembered for many years as a great friend of the labour movement, of the Irish-Australian community and of liberal and progressive causes generally. He was well-served by his first biographer, his niece Nettie Palmer, whose Henry Bournes Higgins: A Memoir (1931) created an enduring Higgins mythology. John Rickard's 1984 H. B. Higgins: The Rebel as Judge partly demolished this myth, but was a generally sympathetic biography. The H.B. Higgins Chambers in Sydney, founded by radical industrial lawyers, is named for him.

Further, Higgins is commemorated by the federal electorate of Higgins in Melbourne, and by the Canberra suburb of Higgins, Australian Capital Territory.

References

- ^ Irish Independent, 8 February 1906. p. 7.

Further reading

- Rickard, John (1984), H.B. Higgins. The Rebel as Judge, George Allen and Unwin, Sydney, New South Wales. ISBN 0-86861-681-8

- 1851 births

- 1929 deaths

- Attorneys General of Australia

- Justices of the High Court of Australia

- Lawyers from Melbourne

- Members of the Australian House of Representatives

- Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Northern Melbourne

- Members of the Cabinet of Australia

- Politicians from County Mayo

- Protectionist Party members of the Parliament of Australia

- Melbourne Law School alumni

- People educated at Wesley College, Dublin

- Australian Queen's Counsel

- Carlton Football Club administrators