Hope Diamond: Difference between revisions

Damienjoseph (talk | contribs) |

Damienjoseph (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

=== Legend === |

=== Legend === |

||

According to specious later accounts, the original form of the Hope Diamond was stolen from an eye of a sculpted statue of the goddess [[Sita Devi|Sita]], the wife of [[Rama]], the seventh [[Avatar (Hinduism)|avatar]] of [[Vishnu]]. |

According to specious later accounts, the original form of the Hope Diamond was stolen from an eye of a sculpted statue of the goddess [[Sita Devi|Sita]], the wife of [[Rama]], the seventh [[Avatar (Hinduism)|avatar]] of [[Vishnu]]. |

||

<ref>The story goes that there was statue that was built in honor of the God Sita. All the villagers placed valuable jewelry on the statue as offering. The statue was marvelous one, it was decorated with diamonds for eyes, gold and stone.</ref> |

|||

However, much like the "curse of [[Tutankhamun]]", this general type of "legend" was the invention of Western authors during the Victorian era,<ref>Keys, David. "[http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/curse-of-the-mummys-tomb-invented-by-victorian-writers-626787.html Curse of the mummy's tomb invented by Victorian writers]". ''[[The Independent]]''. 31 December 2000.</ref> and the specific legends about the Hope Diamond's "cursed origin" were invented in the early 20th century to add mystique to the stone and increase its sales appeal; see [[Hope Diamond#The "Curse"|The "Curse"]] section below. |

However, much like the "curse of [[Tutankhamun]]", this general type of "legend" was the invention of Western authors during the Victorian era,<ref>Keys, David. "[http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/curse-of-the-mummys-tomb-invented-by-victorian-writers-626787.html Curse of the mummy's tomb invented by Victorian writers]". ''[[The Independent]]''. 31 December 2000.</ref> and the specific legends about the Hope Diamond's "cursed origin" were invented in the early 20th century to add mystique to the stone and increase its sales appeal; see [[Hope Diamond#The "Curse"|The "Curse"]] section below. |

||

Revision as of 22:41, 16 January 2011

Hope Diamond in the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History | |

| Weight | 45.52[1] |

|---|---|

| Color | Fancy Dark Grayish Blue (GIA) |

| Cut | Antique cushion |

| Country of origin | Indian subcontinent |

| Mine of origin | Kollur mine |

| Discovered | Unknown. Present form first documented in the inventory of jewel merchant Daniel Eliason in 1812. |

| Cut by | Unknown. Recut from the French Blue diamond after 1791; slightly reshaped by Harry Winston between 1949 and 1958 |

| Original owner | Unknown. Acquired by Henry Philip Hope before 1839. |

| Owner | Smithsonian Natural History Museum |

| Estimated value | $200–$250 million USD |

The Hope Diamond (previously "Le bleu de France") is a large, 45.52 carats (9.104 g),[1] deep-blue diamond, housed in the Smithsonian Natural History Museum in Washington, D.C. The Hope Diamond is blue to the naked eye because of trace amounts of boron within its crystal structure, but it exhibits red phosphorescence after exposure to ultraviolet light.[2][3] It is classified as a Type IIb diamond, and is famous for supposedly being cursed. It received its newest setting on November 18th, 2010.

Physical properties

An examination in December 1988 by the Gemological Institute of America's Gem Trade Lab (GIA-GTL) showed the diamond to weigh 45.52 carats (9.104 g) and described it as "fancy dark greyish-blue." A re-examination in 1996 slightly rephrased that description as "fancy deep greyish-blue."[4] The stone exhibits an unusually intense and strongly-colored type of luminescence: after exposure to short-wave ultraviolet light, the diamond produces a brilliant red phosphorescence ('glow-in-the-dark' effect) that persists for some time after the light source has been switched off. The clarity was determined to be VS1, with whitish graining present. The cut was described as being "cushion antique brilliant with a faceted girdle and extra facets on the pavilion." The dimensions in terms of length, width, and depth are 25.60mm × 21.78mm × 12.00mm (1in × 7/8in × 15/32in).

In 2010, the diamond was removed from its setting in order to scientifically measure its chemical composition; after boring a hole ten ångströms (four-billionths of an inch) deep, preliminary results detected the presence of boron, hydrogen and possibly nitrogen; the boron concentration varies from zero to eight parts per million.[5]

Color

In popular literature, many superlatives have been used to describe the Hope Diamond as a "superfine deep blue", often comparing it to the color of a fine sapphire "blue of the most beautiful blue sapphire" (Deulafait). Other references include Mawe (1823), Ball (1835), Bruton (1978), Tolansky (1962). However, these descriptions are somewhat exaggerated.[6]

As coloured diamond expert Stephen Hofer points out, blue diamonds similar to the Hope can be shown by colorimetric measurements to be grayer (lower in saturation) than blue sapphires.[7] In 1996 The Gemological Institute of America's Gem Trade Lab (GIA-GTL) examined the diamond and using their proprietary scale, graded it fancy deep grayish blue. Visually, the gray modifier (mask) is so dark (indigo) that it produces an "inky" effect appearing almost blackish-blue in incandescent light.[6] Current photographs of the Hope Diamond utilize high-intensity light sources that tend to maximize the brilliance of gemstones.[8]

History

Legend

According to specious later accounts, the original form of the Hope Diamond was stolen from an eye of a sculpted statue of the goddess Sita, the wife of Rama, the seventh avatar of Vishnu. [9]

However, much like the "curse of Tutankhamun", this general type of "legend" was the invention of Western authors during the Victorian era,[10] and the specific legends about the Hope Diamond's "cursed origin" were invented in the early 20th century to add mystique to the stone and increase its sales appeal; see The "Curse" section below.

The Tavernier Blue

The first known precursor to the Hope Diamond was the Tavernier Blue diamond, a crudely cut triangular shaped stone of 115 carats (23.0 g) named for the French merchant-traveler Jean-Baptiste Tavernier who brought it to Europe. His book, the Six Voyages (Le Six Voyages de...), contains sketches of several large diamonds he sold to Louis XIV in 1669; while the blue diamond is shown among these, Tavernier makes no direct statements about when and where he obtained the stone. The historian Richard Kurin builds a plausible case for 1653 as the year of acquisition,[11] and an origin from the Kollur mine in Guntur district Andhra Pradesh (then a part of the Golconda kingdom), India.[12][13][14] But the most that can be said with certainty is that Tavernier obtained the blue diamond during one of his five voyages to India between the years 1640 and 1667.

Early in the year 1669, Tavernier sold this blue diamond along with approximately one thousand other diamonds to King Louis XIV of France for 220,000 livres, the equivalent of 147 kilograms of pure gold.[15] In a newly published historical novel, The French Blue, gemologist/historian Richard W. Wise proposes a new theory. He contends that the patent of nobility granted Tavernier by Louis XIV was a part of the payment for the Tavernier Blue. During that period Colbert, the king's Finance Minister, regularly sold offices and noble titles for cash. An outright patent of nobility, according to Wise, was worth approximately 500,000 livres making a total of 720,000 livres, a price much closer to the true value of the gem.[16] There has been some controversy regarding the actual weight of the stone; Morel believes that the 112 3/16 carats stated in Tavernier's invoice would be in old French carats, thus 115.28 metric carats.

The French Blue

In 1678, Louis XIV commissioned the court jeweller, Sieur Pitau, to recut the Tavernier Blue, resulting in a 67.125 carats (13.4250 g) stone which royal inventories thereafter listed as the Blue Diamond of the Crown of France (diamant bleu de la Couronne de France[17]), but later English-speaking historians have simply called it the French Blue. The king had the stone set on a cravat-pin.[18]

In 1749, King Louis XV had the French Blue set into a more elaborate jewelled pendant for the Order of the Golden Fleece, but this fell into disuse after his death. Marie Antoinette is commonly cited as a victim of the diamond's "curse", but she never wore the Golden Fleece pendant, which was reserved for the use of the king.[citation needed] During the reign of her husband, King Louis XVI, she used many of the French Crown Jewels for her own personal adornment by having the individual gems placed into new settings and combinations, but the French Blue remained in this pendant except for a brief time in 1787, when the stone was removed for scientific study by Mathurin Jacques Brisson and returned to its setting soon after.

On September 11, 1792[19], while Louis XVI and his family were confined in the Palais des Tuileries during the early stages of the French Revolution, a group of thieves broke into the Garde-Meuble (Royal Storehouse) and stole most of the Crown Jewels. While many jewels were later recovered, including other pieces of the Order of the Golden Fleece, the French Blue was not among them and it disappeared from history.

Disappearance

The Hope Diamond was long believed to have been cut from the French Blue, but this remained unconfirmed until a three-dimensional leaden model of the latter was recently rediscovered in the archives of the French Natural History Museum in Paris. Previously, the dimensions of the French Blue had been known only from two drawings made in 1749 and 1789; although the model slightly differs from the drawings in some details, these details are identical to features of the Hope Diamond, allowing CAD technology to digitally reconstruct the French Blue around the recut stone.[20][21]

Historians Germain Bapst and Bernard Morel suggested that one robber, Cadet Guillot, took the French Blue, the Côte-de-Bretagne Spinel, and several other jewels to Le Havre and then to London, where the French Blue was cut into two pieces. Morel adds that in 1796, Guillot attempted to resell the Côte-de-Bretagne in France but was forced to relinquish it to a fellow thief, Lancry de la Loyelle, who put Guillot into debtors' prison.

Conversely, the historian Richard Kurin speculates that the "theft" of the French Crown Jewels was in fact engineered by the revolutionary leader Georges Danton as part of a plan to bribe the opposing military commander, Duke Karl Wilhelm of Brunswick. When under attack by Napoleon in 1805, Karl Wilhelm may have had the French Blue recut to disguise its identity; in this form, the stone could have come to England in 1806, when his family fled there to join his daughter Caroline of Brunswick. Although Caroline was the wife of the Prince Regent George (later George IV of the United Kingdom), she lived apart from her husband, and financial straits sometimes forced her to quietly sell her own jewels to support her household.

Caroline's nephew, Duke Karl Friedrich, was later known to possess a 13.75 carats (2.750 g) blue diamond which was widely thought to be another piece of the French Blue. However, this smaller diamond's present whereabouts are unknown, and the recent CAD reconstruction of the French Blue fits too tightly around the Hope Diamond to allow for the existence of such a sister stone.

George IV

A blue diamond with the same shape, size, and color as the Hope Diamond was recorded by John Francillon in the possession of the London diamond merchant Daniel Eliason in September 1812, the earliest point when the history of the Hope Diamond can be definitively fixed. It is often pointed out that this date was almost exactly 20 years after the theft of the French Blue, just as the statute of limitations for the crime had expired.

Eliason's diamond may have been acquired by King George IV of the United Kingdom; there is no record of the ownership in the Royal Archives at Windsor, but some secondary evidence exists in the form of contemporary writings and artwork, and George IV tended to co-mingle the state property of the Crown Jewels with family heirlooms and his own personal property. After his death in 1830, it has been alleged that some of this mixed collection was stolen by his mistress, Lady Conyngham, and some of his remaining personal items were discreetly liquidated to cover the many debts he had left behind him. In either case, the blue diamond was not retained by the British royal family.

The Hope family

In 1839, the Hope Diamond appeared in a published catalog of the gem collection of Henry Philip Hope, of a prominent Anglo-Dutch banking family. The stone was set in a fairly simple medallion surrounded by many smaller white diamonds, which he sometimes lent to Louisa Beresford, the widow of his brother Thomas Hope, for society balls. Henry Philip Hope died in 1839, the same year as the publication of his collection catalog. His three nephews, the sons of his brother Thomas, fought in court for ten years over his inheritance, and ultimately the collection was split up.

The oldest nephew, Henry Thomas Hope, received eight of the most valuable gems including the Hope Diamond. It was put on display in the Great Exhibition of London in 1851 and Paris Exhibition Universelle in 1855, but was usually kept in a bank vault. In 1861, his only child, Henrietta, married Henry Pelham-Clinton, Earl of Lincoln. When Hope died on December 4, 1862, his wife Anne Adele inherited the gem, but feared that the profligate lifestyle of her son-in-law (now the 6th Duke of Newcastle) might cause him to sell the Hope properties.

Upon Adele's death in 1884, the entire Hope estate, including the Hope diamond, was entailed to Henrietta's younger son, Henry Francis, on the condition that he change his surname when he reached legal majority. As Lord Francis Hope, this grandson received his legacy in 1887. However, Francis had only a life interest to his inheritance, meaning he could not sell any part of it without court permission.

On November 27, 1894, Lord Francis married his mistress, American actress May Yohe. She later claimed she had worn the diamond at social gatherings (and had an exact replica made for her performances), but he claimed otherwise. Lord Francis lived beyond his means, and it eventually caught up with him. In 1896, his bankruptcy was discharged, but, as he could not sell the Hope Diamond until he had the court's permission, his wife supported them. In 1901, he was free to sell the Hope Diamond, but May ran off with Putnam Strong, son of former New York City mayor William L. Strong. Francis divorced her in 1902.

Lord Francis sold the diamond for £29,000 (£Error when using {{Inflation}}: |end_year=2,024 (parameter 4) is greater than the latest available year (2,023) in index "UK". as of 2024),[22] to Adolph Weil, a London jewel merchant. Weil later sold the stone to U.S. diamond dealer Simon Frankel, who took it to New York. There, it was evaluated to be worth $141,032 (equal to £28,206 at the time). In 1908, Frankel sold the diamond for $400,000 to a Salomon or Selim Habib, reportedly in behalf of Sultan Abdul Hamid of Turkey; however, on June 24, 1909, the stone was included in an auction of Habib's assets to settle his own debts, and the auction catalog explicitly stated that the Hope Diamond was one of only two gems in the collection which had never been owned by the Sultan. The Parisian jewel merchant Simon Rosenau bought the Hope Diamond for 400,000 francs and resold it in 1910 to Pierre Cartier for 550,000 francs.

Cartier, McLean, and Winston

Pierre Cartier first offered the Hope Diamond to U.S. socialite Evalyn Walsh McLean in 1910.[citation needed] She initially rejected the stone in the Hope family's old setting, but she found the stone much more appealing when Cartier reset it in a more modern style and told elaborate stories about its supposed "cursed" origins. The new setting was the current platinum framework surrounded by a row of sixteen alternating Old Mine Cut and pear-shaped, Old Mine Cut diamonds. Eventually, McLean bought the new necklace and afterwards wore it at every social occasion she organized.[citation needed] When she died in 1947, she willed the diamond to her grandchildren, though her property would be in the hands of trustees until the eldest had reached 25 years of age, which would have meant at least 20 years in the future. However, the trustees gained permission to sell her jewels to settle her debts, and in 1949 sold them to New York diamond merchant Harry Winston.

Over the next decade, Winston exhibited McLean's necklace in his "Court of Jewels," a tour of jewels around the United States, as well as various charity balls and the August 1958 Canadian National Exhibition. [citation needed] At some point, he also had the Hope Diamond's bottom facet slightly recut to increase its brilliance.

The Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian mineralogist George Switzer is credited with persuading Harry Winston to donate the Hope Diamond to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History for a proposed national gem collection to be housed at the museum.[23] On November 10, 1958, Winston donated the diamond to the Smithsonian Institution, where it became Specimen #217868,[24] sending it through U.S. Mail in a plain brown paper bag. Winston never believed in any of the tales about the curse and died of a heart attack at the age of 82 on December 28, 1978.

For its first four decades in the National Museum of Natural History, the Hope Diamond lay in its necklace inside a glass-fronted safe as part of the gems and jewelry gallery, except for a few brief excursions: a 1962 exhibition in the Louvre; the 1965 Rand Easter Show in Johannesburg, South Africa; and two visits back to Harry Winston's premises in New York City for a 50th anniversary celebration in 1988 and some minor cleaning and restoration in 1996.

When the Smithsonian's gallery was renovated in 1997, the necklace was moved onto a rotating pedestal inside a cylinder made of 3-inch (76 mm) thick bulletproof glass in its own display room, adjacent to the main exhibit of the National Gem Collection in the Janet Annenberg Hooker Hall of Geology, Gems, and Minerals. The Hope Diamond is the most popular jewel on display.

On February 9, 2005, the Smithsonian Institution published the findings of its year-long computer-aided geometry research on the gem and officially acknowledged the Hope Diamond is part of the stolen French Blue crown jewel.[25]

On August 19, 2009, the Smithsonian Institution announced that the Hope Diamond is to get a temporary new setting to celebrate a half-century at the National Museum of Natural History. Starting in September, the 45.52-carat (9.104 g) diamond will be exhibited as a stand-alone gem with no setting. It has been removed from its setting for cleaning from time to time, but this is the first time it will be on public view by itself. Previously it has been shown in a platinum setting, surrounded by 16 white pear-shaped and cushion-cut diamonds, suspended from a chain containing forty-five diamonds.

The Hope was scheduled to return to its traditional setting in late 2010.[26]

The Museum national d'Histoire naturelle (MNHN) in Paris

On November 2008, the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle published a bilingual French/English press release [27] about the discovery of a unique and previously unknown lead cast of the French Blue diamond in the MNHN gemmological collections in Paris, and the resulting investigation by an international group of researchers. Compared to the previously available drawings, the model showed numerous unsuspected facets and corrected the actual thickness of the stone, leading to CAD analysis and the creation of the first numeric reconstruction of the French Blue including a virtual snapshot video.

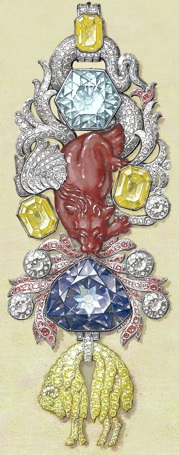

The emblem of the Golden Fleece of Louis XV was numerically reconstructed around the French Blue, including the "Côte de Bretagne" spinel of 107 carats (21.4 g), the "Bazu" diamond of 32.62 carats (6.524 g), 3 oriental topazes (yellow sapphires), five brillants of up to 5 carats (1,000 mg) brillants and nearly 300 smaller diamonds. Special care was taken to reconstruct the major gemstones from CAD analysis and knowledge of historical gemsetting techniques.

As part of the investigation, the "Tavernier Blue" diamond was also reconstructed from the original French edition of Tavernier's Voyages (rather than the later London edition that somewhat distorted and modified Tavernier's original figures), and the Smithsonian Institution provided ray-tracing and optical spectroscopic data about the Hope diamond.

The lead cast of the French Blue had been catalogued at the museum in 1850. it was given by Charles Archard, a prominent jeweler in Paris at that time of the same generation as René Just Haüy (who died in 1822). Most likely, the lead cast was given near 1815, given the other entries of the 1850 catalogue. The model was accompanied by a label stating that the "French Blue" was in the possession of "Mr. Hoppe of London". Other archives at the Muséum suggests that Achard had Hope as a good customer for many long years, particularly for blue gems.[28]

This seems to indicate that HP Hope might have possessed the French Blue that he acquired some time after the 1792 robbery in Paris. in 1794-1795, the Hopes left Holland to escape Napoleon's armies and moved to London.[29] At about the same time, Cadet Guillot, who supposedly stolen the Golden Fleece, arrived in London about the same time.[30] It is also known from Bapst that Cadet contracted with a French aristocrat, Lancry de la Loyelle, in 1796 to sell the 107-carat (21.4 g) spinel-dragon of the Golden Fleece. In 1802, Hope sold his assets and the continental blockade by Napoleon led the Hope bank into serious financial crisis as early as 1808, peaking during the winter of 1811-1812 [31] Like many kings before him, Hope could have pawned the French Blue to Eliason to get cash at a time the sterling was highly depreciated.[32] However the diamond had to be quickly recut to disguise its identity, otherwise the French government would have sued its owners.[28] Hope recovered it later, around 1824, when Eliason died at a time Hope's financial situation has been restored thanks to the Barings, who saved the Hope bank in the years 1812-1820.[32] Then, the lead cast of the French Blue and the "Hope" diamond are likely to have been created in the same workshop, possibly in London a little before 1812.

The MNHN in Paris commissioned the first exact cubic zirconia replicas of Tavernier and French Blue diamonds from lapidary Scott Sucher. These replicas have been completed and are currently on view together with the French crown jewels and the Great Sapphire of Louis XIV, a fantastic Moghul-cut sapphire of 135.7 carats (27.14 g).

The most fabulous jewel in the history of French jewelry, the emblem of the Golden Fleece of King Louis XV of France, was recreated as accurately as possible from 2007-2010. The original Golden Fleece of the color Adornment, created in 1749 by the king’s jeweler Pierre-André Jacqumin, was alas stolen and broken in 1792. The jewel contained the French Blue and the Bazu diamonds, as well as the Côte de Bretagne spinel and hundreds of smaller diamonds. Three years of work were needed to recreate the jewel that highlighted the incredible skill of its original designers. The reconstructed jewel was first presented by Herbert Horovitz, with François Farges of the MNHN, at the former Royal Storehouse in Paris on June 30, 2010, where the original had been stolen 218 years before.

This amazing emblem could be reconstructed thanks to an unknown drawing of the Golden Fleece rediscovered in the 80’s in Switzerland but also thanks to the recent rediscovery of the two blue diamonds that ornamented the jewel (Farges et al., 2008). The jewel included the mythic French Blue diamond, 69 carats (13.8 g), masterpiece recut of the Tavernier Blue by court jeweler Jean Pitau (c. 1617 - 1676), cut in 1673 for Louis XIV. The lead cast of this diamond has been rediscovered in Paris in 2007, hence, its exact rendition (Farges et al., 2009).

This emblem has another great blue diamond, which was later named the Bazu in reference to Bazu, who sold it to Louis XIV in 1669 (Morel, 1988). This diamond was recut in 1749 as a baroque cushion weighting 32.62 carats (6.524 g). The 1791 inventory mentioned that the Bazu diamond was "light sky blue" ("d’une eau un peu céleste"; Bion et al., 1791), consistent with the fact that the Golden Fleece of the Color Adornment was made of great colored gems. Based on documents kept in a private collection (Farges et al., 2008), it could be shown that this diamond was not hexagonal-shaped, as some historians previously taught (Bapst, 1889; Morel, 1988 ; Tillander, 1995), but rounded squared (according to the 1774 and 1791 Inventories), more like the Régent diamond (Farges et al., 2009). Farges from the MNHN will soon publish that the hexagonal cut is inconsistent historically and gemologically speaking. In fact, this stone referred to another version of Louis XV’s great Golden Fleece, made out of blue sapphires instead of blue diamonds (Farges et al., 2008). This version appears to have never been manufactured but only suggested to the king as an alternative to the effective final version, bearing two blue diamonds. Both blue diamonds replicas were cut by Scott Sucher using cubic zirconia, deep- and light blue in color respectively.

The Côte de Bretagne dragon is the third of the great gems of the emblem. Its replica was made out on the basis of a wax replica sculpted by Pascal Monney, based on 3D scaled pictures by François Farges of the original object displayed at the Galerie d’Apollon at the Louvre Museum. The internationally acclaimed artist Etienne Leperlier cast a “crystal” lead glass duplicate of the wax replica of the carved Côte de Bretagne. Its pigmentation is made out of gold and manganese pigments to simulate as close as possible the original color of the spinel.

The 500+ remaining "diamonds" were cut from cubic zirconia using a baroque cushion cut. The colored diamonds (red and yellow, as for the flames and the fleece itself) were originally colorless and then painted, following what Jacqumin did for the original Golden Fleece that was completed in 1749. As the original was most likely made out of gold plated with silver, it was decided to realize a matrix mostly made out of silver (925 grade) to constrain the cost of the jewel without compromising the final quality. The silver matrix was then carved by Jean Minassian from Geneva, who rediscovered from the available historical drawings the delicate three-dimensional distribution of the various elements of the dragon (wings, tail) and of the palms around which the dragon is suspended. Casts were manufactured thanks to the help of Andreas Altmann, allowing other copies to be made in the future. Amico Bifulci gilded some parts of the silver matrix in order to recreate the probable and most elegant original association between gold and silver that most likely prevailed in the original jewel. All stones were then set according to 18th century techniques. Finally, a luxury box containing the Golden Fleece was also recreated out by Frédéric Viollet using crimson-colored Morocco leather ("maroquin cramoisi"). The box was then gilded by Didier Montecot of Paris to the arms of Louis XV, using the king’s original iron stamp made by the Simier house, the official bookbinders of the kings of France. A dark red cramoisi ribbon, made of crimson satin moire, holds the jewel inside the box.

100 or more invited guests of H. Horovitz included Martin du Daffoy, the celebrated historian and jeweller on Place Vendôme in Paris, the Président and Directors of the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle in Paris, who supported this work. The event was filmed by Gédéon programmes for a documentary on the French Blue diamond, to be presented by 2011 worldwide.

The "Curse"

A New Zealand newspaper article in 1888 described the supposedly lurid history of the Hope Diamond, including a claim that it was "said once to have formed the single eye of a great idol", as part of a confused description that also claimed that its namesake owner had personally "brought it from India", and that the diamond's true color was "white, [although] when held to the light, it emits the most superb and dazzling blue rays."[33]

An early account of the Hope Diamond's "cursed origins" was a fanciful and anonymously written newspaper article in The Times on June 25, 1909. However, an article entitled "Hope Diamond Has Brought Trouble To All Who Have Owned It" had appeared in the Washington Post on January 19, 1908.[34]

A few months later, this was compounded by The New York Times on November 17, 1909, which wrongly reported that the diamond's former owner, Selim Habib, had drowned in a shipwreck near Singapore; in fact, it was a different person with the same name, not the owner of the diamond. The jeweler Pierre Cartier further embroidered the lurid tales to intrigue Evalyn Walsh McLean into buying the Hope Diamond in 1911.

One likely source of inspiration was Wilkie Collins' 1868 novel The Moonstone, which created a coherent narrative from vague and largely disregarded legends which had been attached to other diamonds such as the Koh-i-Nur and the Orloff diamond.

According to these stories, Tavernier stole the diamond from a Hindu temple where it had been set as one of two matching eyes of an idol, and the temple priests then laid a curse on whoever might possess the missing stone. Largely because the other blue diamond "eye" never surfaced, historians dismissed the fantastical story. Furthermore, the legend claimed that Tavernier died of fever soon after and that his body was torn apart by wolves, but the historical record shows that he actually lived to the age of 84.

The Hope Diamond was also blamed for the unhappy fates of other historical figures vaguely linked to its ownership, such as the falls of Madame Athenais de Montespan and French finance minister Nicolas Fouquet during the reign of Louis XIV of France; the beheadings of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette and the rape and mutilation of the Princesse de Lamballe during the French Revolution; and the forced abdication of Turkish Sultan Abdul Hamid who had supposedly killed various members of his court for the stone (despite the annotation in Habib's auction catalog).

Even the jewelers who may have handled the Hope Diamond were not spared from its reputed malice: The insanity and suicide of Jacques Colot, who supposedly bought it from Eliason, and the financial ruin of the jeweler Simon Frankel, who bought it from the Hope family, were linked to the stone. But although he is documented as a French diamond dealer of the correct era, Colot has no recorded connection with the stone, and Frankel's misfortunes were in the midst of economic straits that also ruined many of his peers.

The legend further includes the deaths of numerous other characters who had been previously unknown: Diamond cutter Wilhelm Fals, killed by his son Hendrik, who stole it and later committed suicide; Francois Beaulieu, who received the stone from Hendrik but starved to death after selling it to Daniel Eliason; a Russian prince named Kanitowski, who lent it to French actress Lorens Ladue and promptly shot her dead on the stage, and was himself stabbed to death by revolutionaries; Simon Montharides, hurled over a precipice with his family. However, the existence of only a few of these characters has been verified historically, leading researchers to conclude that most of these persons are fictitious.

The actress May Yohe made many attempts to capitalize on her identity as the former wife of the last Hope to own the diamond, and sometimes blamed the Hope for her misfortunes. In July 1902, months after Lord Francis divorced her, she told police in Australia that her lover, Putnam Strong, had abandoned her and taken her jewels. Incredibly, the couple reconciled, married later that year, but divorced in 1910. On her third marriage by 1920, she persuaded film producer George Kleine to back a 15-episode serial The Hope Diamond Mystery, which added fictitious characters to the tale. It was not successful. In 1921, she hired Henry Leyford Gates to help her write The Mystery of the Hope Diamond, in which she starred as Lady Francis Hope. The film added more characters, including a fictionalized Tavernier, and added Marat among the diamond's "victims". She also wore her copy of the Hope, trying to generate more publicity to further her career.

Lord Francis Hope married Olive Muriel Thompson in 1904. They had three children before she died suddenly in 1912, a tragedy that has been attributed to The Curse.

Evalyn Walsh McLean added her own narrative to the story behind the blue jewel, including that one of the owners was Catherine the Great. McLean would bring the Diamond out for friends to try on, including Warren G. Harding and Florence Harding. McLean often strapped the Hope to her pet dog's collar while in residence at Friendship, in northwest Washington D.C.. There are also stories that she would frequently misplace it at parties,[35] and then make a children's game out of finding the Hope.

However, since the diamond was put in the care of the Smithsonian Institution, there have been no unusual incidents related to it.

A new mounting

The stone is to be temporarily reset in a newly designed necklace, created by the Harry Winston firm. Three designs for the new setting, all white diamonds and white metal, were created and the public was allowed to vote on them via the internet. The winning necklace will debut sometime in 2010. The Hope has been displayed as a loose gem since late summer of 2009 (see above image).

See also

References

- ^ a b Hevesi, Dennis (2008-04-06). "George Switzer, 92, Dies; Started a Gem Treasury". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ^ Schmid, Randolph E. Strangely and uniquely, the diamond glows only after the light has been switched off. The glow can last for anything up to 2 minutes. "UV Light Makes Hope Diamond Glow Red". ABC News. January 7, 2008.

- ^ Hatelberg, John Nels. "The Hope Diamond phosphoresces a fiery red color when exposed to ultraviolet light". Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ King,et al., "Characterizing Natural-color Type IIb Blue Diamonds", Gems & Gemology, Vol. 34, #01, p.249

- ^ Caputo, Joseph (November 2010). "Testing the Hope Diamond". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2011-01-15.

- ^ a b Wise, Richard W., Secrets Of The Gem Trade, The Connoisseur's Guide To Precious Gemstones, Ch. 38, p.235 ISBN 0972822380

- ^ Hofer, Stephen, Collecting and Classifying Colored Diamonds, p.414

- ^ Wise, ibid. p.29-30

- ^ The story goes that there was statue that was built in honor of the God Sita. All the villagers placed valuable jewelry on the statue as offering. The statue was marvelous one, it was decorated with diamonds for eyes, gold and stone.

- ^ Keys, David. "Curse of the mummy's tomb invented by Victorian writers". The Independent. 31 December 2000.

- ^ Kurin, Richard Hope Diamond, The Legendary History of a Cursed Gem, p.29-30

- ^ India Before Europe, C.E.B. Asher and C. Talbot, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0521809045, p. 40

- ^ A History of India, Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund, Edition: 3, Routledge, 1998, p. 160; ISBN 0415154820

- ^ Deccan Heritage, H. K. Gupta, A. Parasher and D. Balasubramanian, Indian National Science Academy, 2000, p. 144, Orient Blackswan, ISBN 8173712859

- ^ Morel, Bernard, The French Crown Jewels, p.158.

- ^ Wise, Richard W., The French Blue, Brunswick House Press, 2010, Afterword p.581. ISBN 978-0-9728223-6-7.

- ^ Farges, François "Two new discoveries concerning the "diamant bleu de la Couronne" ("French Blue" diamond) at the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle in Paris. Stanford University & Le Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle. September 18, 2008.

- ^ Morel, p.166

- ^ http://www.rlsbb.com/2010/12/21/national-geographic-secrets-of-the-hope-diamond-hdtv-xvid-diverge/

- ^ "Francois Farges Abstract". Mineralsciences.si.edu. 2007-02-06. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ Hope Diamond originally came from French crown Associated Press

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ Holley, Joe (2008-03-27). "George Switzer; Got Hope Diamond for Smithsonian". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- ^ "Harry Winston: The Man Who Gave Away The Gem". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 24 August 2009.

The addition of Specimen #217868 to the collection of the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) is perhaps one of Winston's most laudable contributions to the American people.

- ^ "Tech Solves Hope Diamond Mystery". Wired. 2005. Retrieved 2007-12-25.

- ^ "Hope Diamond to get new setting for anniversary". Associated Press. USA Today. August 19, 2009. Retrieved 2011-01-15.

- ^ http://foifoif.free.fr/41AE1384-2E13-4BB9-93CB-4202C2C16DAC_files/presse.pdf

- ^ a b Farges et al., Revue de Gemmologie, Revue de Gemmologie 165, 17-24.

- ^ Buist, M.G. (1974) At spes non fracta: Hope & Co. 1770-1815. Merchant bankers and diplomats at work. Den Haag, Martinus Nijhoff.

- ^ Bapst G. (1889) Les joyaux de la Couronne. Hachette.

- ^ Balfour, Famous diamonds. Antique Collectors' Club Ltd; 6th Revised edition edition (Dec. 2009)

- ^ a b Buist, M.G. (1974) At spes non fracta: Hope & Co. 1770-1815. Merchant bankers and diplomats at work. Den Haag, Martinus Nijhoff..

- ^ "Papers Past — Hawke's Bay Herald — 25 April 1888 — TWO FAMOUS DIAMONDS". Paperspast.natlib.govt.nz. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ Richard Kurin, Hope Diamond: The Legendary History of a Cursed Gem (HarperCollins, 2006), p364; the article, drawn from the New York Herald and appeared on page 4 of the Posts "Miscellany section"; the caption for the illustration was "Remarkable Jewel a Hoodoo".

- ^ Lyons, Leonard (1 May 1947). "Mrs. MacLean's Fabulous Diamond Frequently Lost Like A Bauble". The Miami News. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

Further reading

- François Farges, Scott Sucher, Herbert Horovitz and Jean-Marc Fourcault (September 2008), Revue de Gemmologie, vol. 165, pp. 17–24 (in French) (English version to be published in 2009 in Gems & Gemology)

- Marian Fowler, Hope: Adventures of a Diamond, Ballantine (March, 2002), hardcover, ISBN 0-345-44486-8.

- Stephen C. Hofer, Collecting and Classifying Coloured Diamonds, Ashland Press 1998, ISBN 0-9659410-1-9

- Janet Hubbard-Brown, The Curse of the Hope Diamond (History Mystery), Harpercollins Children's Books (October, 1991), trade paperback, ISBN 0-380-76222-6.

- Richard Kurin, Hope Diamond: The Legendary History of a Cursed Gem, New York: HarperCollins Publishers & Smithsonian Press, 2006. hardcover, ISBN 0060873515.

- Susanne Steinem Patch, Blue Mystery : The Story of the Hope Diamond, Random House (April, 1999), trade paperback, ISBN 0-8109-2797-7; hardcover ISBN 0-517-63610-7.

- Edwin Streeter, The Great Diamonds of the World, George Bell & Sons, (Jan, 1898), hardcover, no ISBN known.

- Richard W. Wise, Secrets Of The Gem Trade, The Connoisseur's Guide To Precious Gemstones, Brunswick House Press (2003) ISBN 0-9728223-8-0

- Richard W. Wise, The French Blue, Brunswick House Press, (2010) ISBN978-0-9728223-6-7