Ibrahim Mirza

Prince Ibrahim Mirza, Solṭān Ebrāhīm Mīrzā, in full Abu'l Fat'h Sultan Ibrahim Mirza (Template:Lang-fa) (April 1540 – 23 February 1577) was a Persian prince of the Safavid dynasty, who was a favourite of his uncle and father-in-law Shah Tahmasp I. He is now mainly remembered as a patron of the arts, especially the Persian miniature. Although most of his library and art collection was apparently destroyed by his wife after his murder, surviving works commissioned by him include the manuscript of the Haft Awrang of the poet Jami which is now in the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.[1]

Biography

He was a grandson of the founder of the Safavid dynasty, Ismail I (1487–1524) by Ismail's fourth son, Prince Shahzadeh ‘Abu'l Fat'h Sultan Moez od-din Bahram Mirza (1518–50), who was Governor of Khorasan 1529–32, Gilan 1536–37 and Hamadan 1546–49, and also a commissioner of manuscripts. Two of his uncles and two of his brothers were to rebel against Tahmasp, but Ibrahim Mirza, who grew up at court, was for long time a favourite, and was appointed Governor of Mashad at the age of sixteen, arriving there in March 1556.[2] The appointment had a nominal element — Tahmasp himself had received his first governorship at the age of four — but was also political, connected to Ibrahim Mirza's mother, who came from the Shirvanshah dynasty.[3]

In 1560 he married Tahmasp's eldest daughter Princess Shahzadeh Alamiyan Gowhar Soltan Beygom (1540 – May 19, 1577); they had one daughter, Gowhar Shad Begum (1561 – after 1582). Around the end of 1562 he was travelling to Ardabil to take up the governorship there, when he was reported to the shah for his reaction to a joke that angered the shah, and the appointment was switched to the much less important governorship of Qa'en in Khorasan.[4] However, in 1564–65 he had to suppress a major tribal revolt of the Takkalu, who used a slave army numbering 10,000.[5]

After a few years the shah's anger had subsided, and Ibrahim Mirza was re-appointed to Mashad by 1565–66, although he was removed again "within a year or two, apparently for his failure to assist in rescuing the shah’s besieged son Solṭān Moḥammad Mīrzā".[6] He was sent to govern Sabzavār until 1574 when, by now 34, he was recalled to the capital at Qazvin to serve as grand master of ceremonies (ešīk-āqāsī-bāšī). When Tahmasp died two years later, he was involved in the struggles at court over the succession, finally supporting the successful Ismail II, who appointed him keeper of the royal seal (mohrdār). However, in less than a year he was killed in Qazvin, along with several other princes, in a general clear-out of potential rivals ordered by Ismail.[7] The new shah, who may have been mentally unstable after spending twenty years in prison, had soon alienated the Qizilbash who were powerful at court, and it seems they had begun to look to Ibrahim Mirza as a possible replacement; the shah himself died, supposedly after consuming poisoned opium, nine months later.[8]

Patron of the arts

Like other Safavid princes Ibrahim Mirza practiced as a poet, artist and calligrapher, and patronized poets, musicians and other artists, but he was especially important for the atelier he maintained for the production of illuminated manuscripts. When Tahmasp, previously the leading patron of Persian painting at the time, ceased to commission manuscripts in the 1540s, Ibrahim Mirza's workshop was for a period the most important in Persia.[9] As a poet he wrote several thousand lines, in Persian and Turkish.[10]

The Freer Jami contains statements by the two calligraphers who copied the text that it was copied at Mashad, and another source states that one of them, Malik al-Daylami, went with Ibrahim Mirza to Mashad in 1556, and stayed for 18 months, before being recalled by the shah; he also tutored the prince in calligraphy. Despite requests from the prince he was not allowed back to Mashad before his death in 1561-62. The second calligrapher, Shah Mahmud Nishapuri, who had scribed the last major commission of Tahmasp, the Khamsa of Nizami, British Library Or. 2265, died in Mashad in 1564-65.[11]

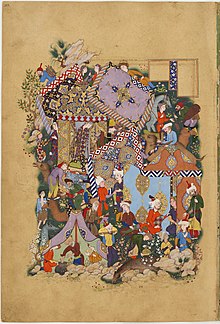

There are 28 full-page miniatures, none signed or dated,[12] but modern attributions have been made, not always finding consensus among scholars, to artists including Shaykh Muhammad, an important artist who is recorded joining Ibrahim Mirza in Sabzavar, and after his death returned to working for the shahs.[13] Shaykh Muhammad may have been responsible for the individualized faces in certain pictures, atypical of Persian painting, and looking forward to the Mughal miniature tradition that was beginning just in these years, as other artists from Tahmasp's atelier joined the service of the Mughal emperor Humayun. Indeed, one artist, Mirza Ali, is claimed by Stuart Cary Welch and others to have contributed to the Freer Jami, while the theory of Barbara Brend that he was the same person as Abd al-Samad would place him working for Humayun and his son Akbar in just these years, first in Kabul and then in India.[14] Another artist who worked for the prince was Ali Asghar, father of Reza Abbasi, the leading artist of the next generation, who was born around 1565, perhaps at Mashad.[15]

Welch suggests that some paintings were made in Qazvin by older artists, such as Aqa Mirak and Muzaffar Ali, who remained there and sent to Mashad.,[16] but the account by another of the prince's calligraphers, Qazi Ahmad, though admittedly full of extravagant praise, makes it clear that Ibrahim Mirza took a good-sized contingent of artists and craftsmen with him to his posts, and spent much time among them.[17] Other artists working on the manuscript have been given the titles of painters A and D, from their work on earlier manuscripts for Tahmasp.[18] Ibrahim Mirza may also have commissioned manuscripts in Qazvin in the 1570s, the best period of production there.[19] The miniatures in the book are crowded with figures, and in the example opposite textiles, too much so for many critics,. It appears Ibrahim Mirza identified himself with Yusuf (Joseph) and the images of him are probably intended as portraits.[20] The manuscript has been described as "the last truly great one produced under the Safavid dynasty".[21]

For Barbara Brend:

Superficially the illustrations to Jami's stories are very similar to those of works for Tahmasp; they are complex compositions of a high level of finish, but there are more figures which are slightly grotesque, more youths with a slightly louche, pussycat smile, and a palette which admits more brown and purple tertiary colours. The eye is pulled restlessly over the page from detail to detail. It is as though the painters had lost confidence in the power of the ostensible narrative subject to interest the viewer, and were searching for other means to hold the attention. Innocence had been lost; the classic works would continue to be illustrated, but only as a vehicle for the painters' skill; they seem no longer to have a mythic hold on the imagination. The future of painting was to lie in more realistic subjects, though their treatment often disguises that realism from us.[22]

After Ibrahim Mirza was murdered, his wife, who only survived him by three months, is recorded as destroying his library and personal possessions, washing the manuscripts in water, smashing what was probably Chinese porcelain, and burning other things. She also washed out a muraqqa or album, containing miniatures by Behzad among others, which her husband had compiled and given her for their wedding.[23] Perhaps she did not want anything to fall into the hands of her brother, who had ordered his death, and who did take over the prince's atelier.[24] Only two manuscripts commissioned by Ibrahim Mirza have survived, the Freer Jami and a much more "modest" manuscript of 1574, now in the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, with just two illustrations.[25] In 1582 his daughter compiled a book containing his poetry, with some miniatures, which survives in two copies, one in the Aga Khan Museum and the other in the Golestan Palace library in Teheran.[26]

-

Freer Jami, attributed to Muzaffar Ali

-

Freer Jami, attributed to Mirza Ali

-

Detail from the Freer Jami

Notes

- ^ Titley, 105.

- ^ Simpson; Welch 24.

- ^ Babaie, 26.

- ^ Simpson; however dates in sources on the prince's life are sometimes contradictory; his birth date can be given as late as 1544 (see Aga Khan Museum below).

- ^ Babaie, 27–8.

- ^ Simpson.

- ^ Simpson

- ^ Abisaab, 49.

- ^ Welch, 23-24; Sudavar, 1

- ^ Simpson

- ^ Titley, 106

- ^ Welch, 31, who lists them all

- ^ Titley, 106; Welch, 24, 118, 123

- ^ Brend. See the Abd al-Samad article for further details

- ^ Simpson; Titley, 108

- ^ Welch, 24

- ^ Simpson; Titley, 105-106; Welch, 23-27

- ^ Welch, 24

- ^ Titley, 103

- ^ Welch, 98-127; Titley, 106

- ^ Welch, 127

- ^ Islamic, 164

- ^ Titley, 105

- ^ Aga Khan Museum

- ^ Simpson

- ^ Simpson; 1582 album Aga Khan Museum

References

- Abisaab, Rula Jurdim, Converting Persia: religion and power in the Safavid Empire, I.B.Tauris, 2004, ISBN 1-86064-970-X, 9781860649707

- Babaie, Sussan, Slaves of the Shah: new elites of Safavid Iran, I.B.Tauris, 2004, ISBN 1-86064-721-9, ISBN 978-1-86064-721-5

- Brend, Barbara. "Another Career for Mirza Ali?" in Newman, Andrew J. (ed), Society and culture in the early modern Middle East: studies on Iran in the Safavid period, Volume 1998, Volume 46 of Islamic history and civilization, BRILL, 2003, ISBN 90-04-12774-7, ISBN 978-90-04-12774-6

- "Islamic" - Brend, Barbara. Islamic art, Harvard University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-674-46866-X, 9780674468665

- Simpson, Marianna S., Ebrāhīm Mīrzā in Encyclopedia Iranica, 1997, online text, accessed February 25, 2011

- Soudavar, Abolala, The Age of Muhammadi, Muqarnas, 2000, PDF

- Titley, Norah M., Persian Miniature Painting, and its Influence on the Art of Turkey and India, 1983, University of Texas Press, 0292764847

- Welch, Stuart Cary. Royal Persian Manuscripts, Thames & Hudson, 1976, ISBN 0-500-27074-0

Further reading

- Simpson, J.R.R. Marianna Shreve (1997). Sultan Ibrahim Mirza's Haft Awrang: A Princely Manuscript from Sixteenth-Century Iran. Yale University Press. hardback: ISBN 978-0-300-06802-3

External links

- Freer Gallery Online exhibition of the Freer Jami