Indicator bacteria

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2015) |

Indicator bacteria are types of bacteria used to detect and estimate the level of fecal contamination of water. They are not dangerous to human health but are used to indicate the presence of a health risk.

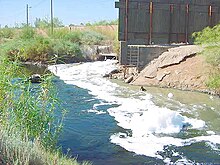

Each gram of human feces contains approximately ~100 billion (1×1011) bacteria.[1] These bacteria may include species of pathogenic bacteria, such as Salmonella or Campylobacter, associated with gastroenteritis. In addition, feces may contain pathogenic viruses, protozoa and parasites. Fecal material can enter the environment from many sources including waste water treatment plants, livestock or poultry manure, sanitary landfills, septic systems, sewage sludge, pets and wildlife. If sufficient quantities are ingested, fecal pathogens can cause disease. The variety and often low concentrations of pathogens in environmental waters makes them difficult to test for individually. Public agencies therefore use the presence of other more abundant and more easily detected fecal bacteria as indicators of the presence of fecal contamination.

Criteria for indicator organisms

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) lists the following criteria for an organism to be an ideal indicator of fecal contamination:[citation needed]

- The organism should be present whenever enteric pathogens are present

- The organism should be useful for all types of water

- The organism should have a longer survival time than the hardiest enteric pathogen

- The organism should not grow in water

- The organism should be found in warm-blooded animals’ intestines.

None of the types of indicator organisms that are currently in use fit all of these criteria perfectly, however, when cost is considered, use of indicators becomes necessary.

Types of indicator organisms

Commonly used indicator bacteria include total coliforms, or a subset of this group, fecal coliforms, which are found in the intestinal tracts of warm blooded animals. Total coliforms were used as fecal indicators by public agencies in the US as early as the 1920s. These organisms can be identified based on the fact that they all metabolize the sugar lactose, producing both acid and gas as byproducts. Fecal coliforms are more useful as indicators in recreational waters than total coliforms which include species that are naturally found in plants and soil; however, there are even some species of fecal coliforms that do not have a fecal origin, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae. Perhaps the biggest drawback to using coliforms as indicators is that they can grow in water under certain conditions.

Escherichia coli (E. coli) and enterococci are also used as indicators.

Current methods of detection

Membrane filtration and culture on selective media

Indicator bacteria can be cultured on media which are specifically formulated to allow the growth of the species of interest and inhibit growth of other organisms. Typically, environmental water samples are filtered through membranes with small pore sizes and then the membrane is placed onto a selective agar. It is often necessary to vary the volume of water sample filtered in order to prevent too few or too many colonies from forming on a plate. Bacterial colonies can be counted after 24 to 48 hours depending on the type of bacteria. Counts are reported as colony forming units per 100 mL (cfu/100 mL).

Fast detections using chromogenic substances

One technique for detecting indicator organisms is the use of chromogenic compounds, which are added to conventional or newly devised media used for isolation of the indicator bacteria. These chromogenic compounds are modified to change color or fluorescence by the addition of either enzymes or specific bacterial metabolites. This enables for easy detection and avoids the need for isolation of pure cultures and confirmatory tests.[2]

Application of antibodies

Immunological methods using monoclonal antibodies can be used to detect indicator bacteria in water samples. Precultivation in select medium must preface detection to avoid detection of dead cells. ELISA antibody technology has been developed to allow for readable detection by the naked eye for rapid identification of coliform microcolonies. Other uses of antibodies in detection use magnetic beads coated with antibodies for the concentration and separation of the oocysts and cysts as described below for immunomagnetic separation (IMS) methods.[2]

IMS/culture and other rapid culture-based methods

Immunomagnetic separation involves purified antigens biotinylated and bound to streptoavidin-coated paramagnetic particles. The raw sample is mixed with the beads, then a specific magnet is used to hold the target organisms against the vial wall and the non-bound material is poured off. This method can be used to recover specific indicator bacteria.[2]

Gene sequence-based methods

Gene sequence-based methods depend on the recognition of exclusive gene sequences particular to specific strains of organisms. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) are gene sequence-based methods currently being used to detect specific strains of indicator bacteria.[2]

Water quality standards for bacteria

Drinking water standards

World Health Organization Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality state that as an indicator organism Escherichia coli provides conclusive evidence of recent fecal pollution and should not be present in water meant for human consumption. In the U.S., the EPA Total Coliform Rule states that a water system is out of compliance if more than 5 percent of its monthly water samples contain coliforms.[3]

Recreational standards

Early studies showed that individuals who swam in waters with geometric mean coliform densities above 2300/100 mL for three days had higher illness rates.[4] In the 1960s, these numbers were converted to fecal coliform concentrations assuming 18 percent of total coliforms were fecal. Consequently, the National Technical Advisory Committee in the US recommended the following standard for recreational waters in 1968: 10 percent of total samples during any 30-day period should not exceed 400 fecal coliforms/100 mL or a log mean of 200/100 mL (based on a minimum of 5 samples taken over not more than a 30-day period).[5]

Despite criticism, EPA recommended this criterion again in 1976, however, the Agency initiated numerous studies in the 1970s and 1980s to overcome the weaknesses of the earlier studies. In 1986, EPA revised its bacteriological ambient water quality criteria recommendations to include E. coli and enterococci.

| Single Sample Maximum Allowable Density per 100 mL | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Type | Indicator | Acceptable Swimming-Associated Gastroenteritis Rate per 1000 Swimmers | Steady State Geometric Mean Indicator Density per 100 mL | Designated Beach Area (upper 75% C.L.) | Moderate Full Body Contact Recreation (upper 82% C.L.) | Lightly Used Full Body Contact Recreation (upper 90% C.L.) | Infrequently Used Full Body Contact Recreation (upper 95% C.L.) |

| Freshwater | E. coli | 8 | 126 | 235 | 298 | 409 | 575 |

| enterococci | 8 | 33 | 61 | 78 | 107 | 151 | |

| Marine Water | E. coli | 19 | 35 | 104 | 158 | 276 | 501 |

Canada's National Agri-Environmental Standards Initiative's approach to characterizing risks associated with fecal water pollution bacterial water quality at agricultural sites is to compare these sites with those at reference sites away from human or livestock sources. This approach generally results in lower levels if E. coli being used as a standard or “benchmark” based on a study that indicated pathogens were detected in 80% of water samples with less than 100 cfu E. coli per 100 mL.[6]

Risk assessment for exposure to pathogens in recreational waters

Most cases of bacterial gastroenteritis are caused by food-borne enteric microorganisms, such as Salmonella and Campylobacter; however, it is also important to understand the risk of exposure to pathogens via recreational waters. This is especially the case in watersheds where human or animal wastes are discharged to streams and downstream waters are used for swimming or other recreational activities. Other important pathogens other than bacteria include viruses such as rotavirus, hepatitis A and hepatitis E and protozoa like giardia, cryptosporidium and Naegleria fowleri.[7] Due to the difficulties associated with monitoring pathogens in the environment, risk assessments often rely on the use of indicator bacteria.

Epidemiological studies

In the 1950s, a series of epidemiological studies were done in the US to determine the relationship between water quality of natural waters and the health of bathers. The results indicated that swimmers were more likely to have gastrointestinal symptoms, eye infections, skin complaints, ear, nose, and throat infections and respiratory illness than non-swimmers and in some cases, higher coliform levels correlated to higher incidence of gastrointestinal illness, although the sample sizes in these studies were small. Since then, studies have been done to confirm causative relations between swimming and certain health outcomes. A review of 22 studies in 1998[8] confirmed that the health risks for swimmers increased as the number of indicator bacteria increased in recreational waters and that E. coli and enterococci concentrations correlated best with health outcomes among all the indicators studied. The relative risk (RR) of illness for swimmers in polluted freshwater versus swimmers in unpolluted water was between 1-2 for the majority of the data sets reviewed. The same study concluded that bacterial indicators were not well correlated to virus concentrations.[8]

Fate and transport of pathogens

Survival of pathogens in waste materials, soil, or water, depends on many environmental factors including temperature, pH, organic matter content, moisture, exposure to light, and the presence of other organisms.[9] Fecal material can be directly deposited, washed into waters by overland runoff, transported through the ground, or discharged to surface waters via sewer lines, pipes, or drainage tiles. Risk of exposure to humans requires: (1) pathogens to survive and be present; (2) pathogens to recreate in surface waters; and (3) individuals to come in contact with water for sufficient time, or ingest sufficient volumes of water to receive an infectious dose. Die-off rates of bacteria in the environment are often exponential, therefore, direct deposition of fecal material into waters generally contribute higher concentrations of pathogens than material that must be transported overland or through the subsurface.

Human exposure

In general, children, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals require a lower dose of a pathogenic organism in order to contract an infection. Presently there are very few studies which are able to quantify the amount of time people are likely to spend in recreational waters and how much water they are likely to ingest. In general, children swim more often, stay in the water longer, submerge their heads more often, and swallow more water. This makes people more fearful of water in the sea as more bacteria will be growing on and around them.

Quantitative microbiological risk assessment

Quantitative microbiological risk assessments (QMRAs) combine pathogen concentrations in water with dose-response relationships and data reflecting potential exposure to estimate the risk of infection.

Data on water exposure are generally collected using questionnaires, but may also be determined from actual measurements of water ingested, or estimated from previously published data. Respondents are asked to report the frequency and timing and location of exposures, detailed information about the amount of water swallowed and head submersion, and basic demographic characteristics such as age, gender, socioeconomic status and family composition. Once sufficient data are collected and determined to be representative of the general population, they are usually fit with distributions, and these distribution parameters are then used in the risk assessment equations. Monitoring data representing occurrence of pathogens, direct measurement of pathogen concentrations, or estimations deriving pathogen concentrations from indicator bacteria concentrations, are also fit with distributions. Dose is calculated by multiplying the concentration of pathogens per volume by volume. Dose-responses can also be fit with a distribution.[10]

Risk management and policy implications

The more assumptions that are made, the more uncertain estimates of risk related to pathogens will be. However, even with considerable uncertainty, QMRAs are a good way to compare different risk scenarios. In a study comparing estimated health risks from exposures to recreational waters impacted by human and non-human sources of fecal contamination, QMRA determined that the risk of gastrointestinal illness from exposure to waters impacted by cattle were similar to those impacted by human waste, and these were higher than for waters impacted by gull, chicken, or pig faeces.[11] Such studies could be useful to risk managers for determining how best to focus their limited resources, however, risk managers must be aware of the limitations of data used in these calculations. For example, this study used data describing concentrations of Salmonella in chicken feces published in 1969.[12] Methods for quantifying bacteria, changes in animal housing practices and sanitation, and many other factors may have changed the prevalence of Salmonella since that time. Also, such an approach often ignores the complicated fate and transport processes that determine bacteria concentrations from the source to the point of exposure.

Addressing bacterial water quality problems

In the US, individual states are allowed to develop their own water quality standards based on EPA's recommendations under the Clean Water Act of 1977. Once water quality standards are approved, states are tasked with monitoring their surface waters to determine where impairments occur, and watershed plans called Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) are developed to direct water quality improvement efforts including changes to allowable bacteria loading by point sources and recommendations for changes to practices that reduce nonpoint-source contributions to bacteria loads. Also, many states have beach monitoring programs to warn swimmers when high levels of indicator bacteria are detected.[13]

References

- ^ Beactiviahealth. "Intestinal Microflora". Activia. Archived from the original on 2012-04-25.

- ^ a b c d Ashbolt, N., Snozzi, G. and M. (2001). Water Quality: Guidelines, Standards and Health. World Health Organization (WHO). Chapter 13: Indicators of Microbial Water Quality. p. 289-316

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (1989-06-29). "Drinking Water; National Primary Drinking Water Regulations; Total Coliforms" (PDF). Washington, DC. 54 FR 27544.

- ^ Stevenson, A (1953). "Studies of Bathing Water Quality and Health". American Journal of Public Health and the Nation's Health. 43 (5): 529–538. doi:10.2105/ajph.43.5_pt_1.529. PMC 1620266. PMID 13040559.

- ^ a b EPA (1986). "Ambient Water Quality Criteria for Bacteria - 1986" (PDF). Document no. EPA-440/5-84-002.

- ^ Edge, TA; El-Shaarawi, A.; Gannon, V.; Jokinen, C.; Kent, R.; Khan, I.U.H.; Koning, W.; Lapen, D.; Miller, J.; Neumann, N.; Phillips, R.; Robertson, W.; Schreier, H.; Scott, A.; Shtepani, I.; Topp, E.; Wilkes, G.; van Bochove, E. (2011). "Investigation of an esherischi coli Environmental Benchmark for Waterborne Pathogens in Agricultural Watersheds in Canada". Journal of Environmental Quality. 40: x–x.

- ^ "Waterborne Pathogens". Montana State. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ^ a b Pruss, A (1998). "Review of epidemiological studies on health effects from exposure to recreational water". International Journal of Epidemiology. 27 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1093/ije/27.1.1. PMID 9563686.

- ^ Guan, Tat Yee; R. A. Holley (2003). "Pathogen Survival in Swine Manure Environments and Transmission of Human Enteric Illness - A Review". Journal of Environmental Quality. 32 (2): 383–392. doi:10.2134/jeq2003.0383.

- ^ Schets, Franciska M.; Schijven, Jack F.; de Roda Husman, Ana Maria (2011). "Exposure assessment for swimmers in bathing waters and swimming pools". Water Research. 45 (7): 2392–2400. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2011.01.025. PMID 21371734.

- ^ Soller, Jeffrey A.; Mary E. Schoen; Timothy Bartrand; John E. Ravenscroft; Nicholas J. Ashbolt (2010). "Estimated human health risks from exposure to recreational waters impacted by human and non-human sources of faecal contamination". Water Research. 44 (16): 4674–4691. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2010.06.049. PMID 20656314.

- ^ Kraft, D. J.; Carolyn Olechowski-Gerhardt; J. Berkowitz; and M.S. Finstein (1969). "Salmonella in Wastes Produced at Commercial Poultry Farms". Applied Microbiology. 18 (5): 703–707. doi:10.1128/AEM.18.5.703-707.1969. PMID 5370457.

- ^ EPA. "Beach Monitoring & Notification". Retrieved 2014-05-31.