Earth's inner core

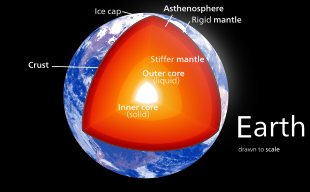

The Earth's inner core is the Earth's innermost part and according to seismological studies, it has been believed to be primarily a solid ball with a radius of about 1,220 kilometres (760 miles), which is about 70% of the Moon's radius.[1][2] It is composed of an iron–nickel alloy and some light elements. The temperature at the inner core boundary is approximately 5700 K (5400 °C).[3]

Discovery

The Earth was discovered to have a solid inner core distinct from its liquid outer core in 1936, by the Danish seismologist Inge Lehmann,[4] who deduced its presence by studying seismograms from earthquakes in New Zealand. She observed that the seismic waves reflect off the boundary of the inner core and can be detected by sensitive seismographs on the Earth's surface. This boundary is known as the Bullen discontinuity,[5] or sometimes as the Lehmann discontinuity.[6] A few years later, in 1940, it was hypothesized that this inner core was made of solid iron; its rigidity was confirmed in 1971.[7]

The outer core was determined to be liquid from observations showing that compressional waves pass through it, but elastic shear waves do not – or do so only very weakly.[8] The solidity of the inner core had been difficult to establish because the elastic shear waves that are expected to pass through a solid mass are very weak and difficult for seismographs on the Earth's surface to detect, since they become so attenuated on their way from the inner core to the surface by their passage through the liquid outer core. Dziewonski and Gilbert established that measurements of normal modes of vibration of Earth caused by large earthquakes were consistent with a liquid outer core.[9] Recent claims that shear waves have been detected passing through the inner core were initially controversial, but are now gaining acceptance.[10]

Composition

Based on the relative prevalence of various chemical elements in the Solar System, the theory of planetary formation, and constraints imposed or implied by the chemistry of the rest of the Earth's volume, the inner core is believed to consist primarily of a nickel-iron alloy. The iron-nickel alloy under core pressure is denser than the core, implying the presence of light elements in the core (e.g. silicon, oxygen, sulfur).[11]

Temperature and pressure

The temperature of the inner core can be estimated by considering both the theoretical and the experimentally demonstrated constraints on the melting temperature of impure iron at the pressure which iron is under at the boundary of the inner core (about 330 GPa). These considerations suggest that its temperature is about 5,700 K (5,400 °C; 9,800 °F).[3] The pressure in the Earth's inner core is slightly higher than it is at the boundary between the outer and inner cores: it ranges from about 330 to 360 gigapascals (3,300,000 to 3,600,000 atm).[12] Iron can be solid at such high temperatures only because its melting temperature increases dramatically at pressures of that magnitude (see the Clausius–Clapeyron relation).[13]

A report published in the journal Science [14] concludes that the melting temperature of iron at the inner core boundary is 6230 ± 500 K, roughly 1000 K higher than previous estimates.

Dynamics

The Earth's inner core is thought to be slowly growing as the liquid outer core at the boundary with the inner core cools and solidifies due to the gradual cooling of the Earth's interior (about 100 degrees Celsius per billion years).[15] Many scientists had initially expected that the inner core would be found to be homogeneous, because the solid inner core was originally formed by a gradual cooling of molten material, and continues to grow as a result of that same process. Even though it is growing into liquid, it is solid, due to the very high pressure that keeps it compacted together even if the temperature is extremely high. It was even suggested that Earth's inner core might be a single crystal of iron.[16] However, this prediction was disproved by observations indicating that in fact there is a degree of disorder within the inner core.[17] Seismologists have found that the inner core is not completely uniform, but instead contains large-scale structures such that seismic waves pass more rapidly through some parts of the inner core than through others.[18] In addition, the properties of the inner core's surface vary from place to place across distances as small as 1 km. This variation is surprising, since lateral temperature variations along the inner-core boundary are known to be extremely small (this conclusion is confidently constrained by magnetic field observations). Recent discoveries suggest that the solid inner core itself is composed of layers, separated by a transition zone about 250 to 400 km thick.[19] If the inner core grows by small frozen sediments falling onto its surface, then some liquid can also be trapped in the pore spaces and some of this residual fluid may still persist to some small degree in much of its interior.

Because the inner core is not rigidly connected to the Earth's solid mantle, the possibility that it rotates slightly faster or slower than the rest of Earth has long been entertained.[20][21] In the 1990s, seismologists made various claims about detecting this kind of super-rotation by observing changes in the characteristics of seismic waves passing through the inner core over several decades, using the aforementioned property that it transmits waves faster in some directions. Estimates of this super-rotation are around one degree of extra rotation per year.

Growth of the inner core is thought to play an important role in the generation of Earth's magnetic field by dynamo action in the liquid outer core. This occurs mostly because it cannot dissolve the same amount of light elements as the outer core and therefore freezing at the inner core boundary produces a residual liquid that contains more light elements than the overlying liquid. This causes it to become buoyant and helps drive convection of the outer core.[citation needed] The existence of the inner core also changes the dynamic motions of liquid in the outer core as it grows and may help fix the magnetic field since it is expected to be a great deal more resistant to flow than the outer core liquid (which is expected to be turbulent).[citation needed]

Speculation also continues that the inner core might have exhibited a variety of internal deformation patterns. This may be necessary to explain why seismic waves pass more rapidly in some directions than in others.[22] Because thermal convection alone appears to be improbable,[23] any buoyant convection motions will have to be driven by variations in composition or abundance of liquid in its interior. S. Yoshida and colleagues proposed a novel mechanism whereby deformation of the inner core can be caused by a higher rate of freezing at the equator than at polar latitudes,[24] and S. Karato proposed that changes in the magnetic field might also deform the inner core slowly over time.[25]

There is an East–West asymmetry in the inner core seismological data. There is a model which explains this by differences at the surface of the inner core – melting in one hemisphere and crystallization in the other.[26] the western hemisphere of the inner core may be crystallizing, whereas the eastern hemisphere may be melting. This may lead to enhanced magnetic field generation in the crystallizing hemisphere, creating the asymmetry in the Earth's magnetic field.[27]

History

Based on rates of cooling of the core, it is estimated that the current solid inner core started solidifying approximately 0.5 to 2 billion years ago[28] out of a fully molten core (which formed just after planetary formation). If true, this would mean that the Earth's solid inner core is not a primordial feature that was present during the planet's formation, but a feature younger than the Earth (the Earth is about 4.5 billion years old).

See also

References

- ^ Monnereau, Marc; Calvet, Marie; Margerin, Ludovic; Souriau, Annie (May 21, 2010). "Lopsided Growth of Earth's Inner Core". Science. 328 (5981): 1014–1017. Bibcode:2010Sci...328.1014M. doi:10.1126/science.1186212. PMID 20395477Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ E. R. Engdahl; E. A. Flynn; R. P. Massé (1974). "Differential PkiKP travel times and the radius of the core". Geophys. J. R. Astron. Soc. 40 (3): 457–463. Bibcode:1974GeoJI..39..457E. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.1974.tb05467.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b D. Alfè; M. Gillan; G. D. Price (January 30, 2002). "Composition and temperature of the Earth's core constrained by combining ab initio calculations and seismic data" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 195 (1–2). Elsevier: 91–98. Bibcode:2002E&PSL.195...91A. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(01)00568-4.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Edmond A. Mathez, ed. (2000). EARTH: INSIDE AND OUT. American Museum of Natural History.

- ^ John C. Butler (1995). "Class Notes - The Earth's Interior". Physical Geology Grade Book. University of Houston. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ Although another discontinuity is named after Lehmann, this usage still can be found: see for example: Robert E Krebs (2003). The basics of earth science. Greenwood Publishing Company. ISBN 0-313-31930-8.,and From here to "hell ," or the D layer, About.com

- ^ Hung Kan Lee (2002). International handbook of earthquake and engineering seismology; volume 1. Academic Press. p. 926. ISBN 0-12-440652-1.

- ^ William J. Cromie (1996-08-15). "Putting a New Spin on Earth's Core". Harvard Gazette. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ A. M. Dziewonski; F. Gilbert (1971-12-24). "Solidity of the Inner Core of the Earth inferred from Normal Mode Observations". Nature. 234 (5330): 465–466. Bibcode:1971Natur.234..465D. doi:10.1038/234465a0.

- ^ Robert Roy Britt (2005-04-14). "Finally, a Solid Look at Earth's Core". Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ Stixrude, Lars; Wasserman, Evgeny; Cohen, Ronald E. (1997-11-10). "Composition and temperature of Earth's inner core". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 102 (B11): 24729–24739. doi:10.1029/97JB02125. ISSN 2156-2202.

- ^ David. R. Lide, ed. (2006–2007). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (87th ed.). pp. j14–13.

- ^ Anneli Aitta (2006-12-01). "Iron melting curve with a tricritical point". Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment. 2006 (12). iop: 12015–12030. arXiv:cond-mat/0701283. Bibcode:2006JSMTE..12..015A. doi:10.1088/1742-5468/2006/12/P12015. or see preprints http://arxiv.org/pdf/cond-mat/0701283 , http://arxiv.org/pdf/0807.0187 .

- ^ S. Anzellini; A. Dewaele; M. Mezouar; P. Loubeyre; G. Morard (2013). "Melting of Iron at Earth's Inner Core Boundary Based on Fast X-ray Diffraction". Science. 340 (6136). AAAS: 464–466. doi:10.1126/science.1233514.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ J.A. Jacobs (1953). "The Earth's inner core". Nature. 172 (4372): 297–298. Bibcode:1953Natur.172..297J. doi:10.1038/172297a0.

- ^ Broad, William J. (1995-04-04). "The Core of the Earth May Be a Gigantic Crystal Made of Iron". NY Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ^ Robert Sanders (1996-11-13). "Earth's inner core not a monolithic iron crystal, say UC Berkeley seismologist". Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ Andrew Jephcoat; Keith Refson (2001-09-06). "Earth science: Core beliefs". Nature. 413 (6851): 27–30. doi:10.1038/35092650. PMID 11544508.

- ^ Kazuro Hirahara; Toshiki Ohtaki; Yasuhiro Yoshida (1994). "Seismic structure near the inner core-outer core boundary". Geophys. Res. Lett. 51 (16). American Geophysical Union: 157–160. Bibcode:1994GeoRL..21..157K. doi:10.1029/93GL03289.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Aaurno, J. M.; Brito, D.; Olson, P. L. (1996). "Mechanics of inner core super-rotation". Geophysical Research Letters. 23 (23): 3401–3404. Bibcode:1996GeoRL..23.3401A. doi:10.1029/96GL03258Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Xu, Xiaoxia; Song, Xiaodong (2003). "Evidence for inner core super-rotation from time-dependent differential PKP traveltimes observed at Beijing Seismic Network". Geophysical Journal International. 152 (3): 509–514. Bibcode:2003GeoJI.152..509X. doi:10.1046/j.1365-246X.2003.01852.xTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ G Poupinet; R Pillet; A Souriau (1983). "Possible heterogeneity of the Earth's core deduced from PKIKP travel times". Nature. 305: 204–206. doi:10.1038/305204a0.

- ^ T. Yukutake (1998). "Implausibility of thermal convection in the Earth's solid inner core". Phys. Earth Planet. Int. 108 (1): 1–13. Bibcode:1998PEPI..108....1Y. doi:10.1016/S0031-9201(98)00097-1.

- ^ S.I. Yoshida; I. Sumita; M. Kumazawa (1996). "Growth model of the inner core coupled with the outer core dynamics and the resulting elastic anisotropy". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 101: 28085–28103. Bibcode:1996JGR...10128085Y. doi:10.1029/96JB02700.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ S. I. Karato (1999). "Seismic anisotropy of the Earth's inner core resulting from flow induced by Maxwell stresses". Nature. 402 (6764): 871–873. Bibcode:1999Natur.402..871K. doi:10.1038/47235.

- ^ Alboussière, T.; Deguen, R.; Melzani, M. (2010). "Melting-induced stratification above the Earth's inner core due to convective translation". Nature. 466 (7307): 744–747. arXiv:1201.1201. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..744A. doi:10.1038/nature09257. PMID 20686572.

- ^ "Figure 1: East–west asymmetry in inner-core growth and magnetic field generation." from Finlay, Christopher C. (2012). "Core processes: Earth's eccentric magnetic field". Nature Geoscience. 5: 523–524. doi:10.1038/ngeo1516.

- ^ Labrosse, Stéphane; Poirier, Jean-Paul; Le Mouël, Jean-Louis (2001-08-15). "The age of the inner core". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 190 (3–4): 111–123. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(01)00387-9.