Insertion reaction

An insertion reaction is a chemical reaction where one chemical entity (a molecule or molecular fragment) interposes itself into an existing bond of typically a second chemical entity e.g.:

- A + B–C → B–A–C

The term only refers to the result of the reaction and does not suggest a mechanism. Insertion reactions are observed in organic, inorganic, and organometallic chemistry. In cases where a metal-ligand bond in a coordination complex is involved, these reactions are typically organometallic in nature and involve a bond between a transition metal and a carbon or hydrogen.[1] It is usually reserved for the case where the coordination number and oxidation state of the metal remain unchanged.[2] When these reactions are reversible, the removal of the small molecule from the metal-ligand bond is called extrusion or elimination.

There are two common insertion geometries— 1,1 and 1,2 (pictured above). Additionally, the inserting molecule can act either as a nucleophile or as an electrophile to the metal complex.[2] These behaviors will be discussed in more detail for CO, nucleophilic behavior, and SO2, electrophilic behavior.

Organic chemistry

Homologation reactions like the Kowalski ester homologation[3] provide simple examples of insertion process in organic synthesis. In the Arndt-Eistert reaction,[4][5] a methylene unit is inserted into the carboxyl-carbon bond of carboxylic acid to form the next acid in the homologous series. Organic Syntheses provides the example of t-BOC protected (S)-phenylalanine (2-amino-3-phenylpropanoic acid) being reacted sequentially with triethylamine, ethyl chloroformate, and diazomethane to produce the α-diazoketone, which is then reacted with silver trifluoroacetate / triethylamine in aqueous solution to generate the t-BOC protected form of (S)-3-amino-4-phenylbutanoic acid.[6]

Mechanistically,[7] the α-diazoketone undergoes a Wolff rearrangement[8][9] to form a ketene in a 1,2-rearrangement. Consequently, the methylene group α- to the carboxyl group in the product is the methylene group from the diazomethane reagant. The 1,2-rearrangement has been shown to conserve the stereochemistry of the chiral centre as the product formed from t-BOC protected (S)-phenylalanine retains the (S) stereochemistry with a reported enantiomeric excess of at least 99%.[6]

A related transformation is the Nierenstein reaction in which a diazomethane methylene group is inserted into the carbon-chlorine bond of an acid chloride to generate an α-chloromethyl ketone.[10][11] An example, published in 1924, illustrates the reaction in a substituted benzoyl chloride system:[12]

Perhaps surprisingly, α-bromoacetophenone is the minor product when this reaction is carried out with benzoyl bromide, a dimeric dioxane being the major product.[13] Organic azides also provide an example of an insertion reaction in organic synthesis and, like the above examples, the transformations proceed with loss of nitrogen gas. When tosyl azide reacts with norbornadiene, a ring expansion reaction takes place in which a nitrogen atom is inserted into a carbon-carbon bond α- to the bridge head:[14]

The Beckmann rearrangement[15][16] is another example of a ring expanding reaction in which a heteroatom is inserted into a carbon-carbon bond. The most important application of this reaction is the conversion of cyclohexanone to its oxime, which is then rearranged under acidic conditions to provide ε-caprolactam,[17] the feedstock for the manufacture of Nylon 6. Annual production of caprolactam exceeds 2 billion kilograms.[18]

Carbenes undergo both intermolecular and intramolecular insertion reactions. Cyclopentene moieties can be generated from sufficiently long-chain ketones by reaction with trimethylsilyldiazomethane, (CH3)3Si–CHN2:

Here, the carbene intermediate inserts into a carbon-hydrogen bond to form the carbon-carbon bond needed to close the cyclopentene ring. Carbene insertions into carbon-hydrogen bonds can also occur intermolecularly:

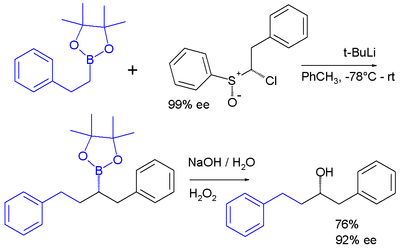

Carbenoids are reactive intermediates that behave similarly to carbenes.[19] One example is the chloroalkyllithium carbenoid reagent prepared in situ from a sulfoxide and t-BuLi which inserts into the carbon-boron bond of a pinacol boronic ester:[20]

Organometallic chemistry

Many reactions in organometallic chemistry involve insertion of one ligand (L) into a metal-hydride or metal-alkyl/aryl bond. Generally it is the hydride, alkyl, or aryl group that migrates onto L, which is often CO, an alkene, or alkyne.

Carbonylations

The insertion of carbon monoxide and alkenes into metal-carbon bonds is a widely exploited reaction with major industrial applications.[21][22]

Such reactions are subject to the usual parameters that affect other reactions in coordination chemistry, but steric effects are especially important in determining the stereochemistry and regiochemistry of the reactions. The reverse reaction, the de-insertion of CO and alkenes, are of fundamental significance in many catalytic cycles as well.

Widely employed applications of migratory insertion of carbonyl groups are hydroformylation and the carbonylative production of acetic acid. The former converts alkenes, hydrogen, and carbon monoxide into aldehydes. The production of acetic acid by carbonylation proceeds via two similar industrial processes. More traditional is the rhodium-based Monsanto acetic acid process, but this process has been superseded by the iridium-based Cativa process.[23][24] By 2002, worldwide annual production of acetic acid stood at 6 million tons, of which approximately 60% is produced by the Cativa process.[23]

The Cativa process catalytic cycle, shown above, includes both insertion and de-insertion steps. The oxidative addition reaction of methyl iodide with (1) involves the formal insertion of the iridium(I) centre into the carbon-iodine bond, whereas step (3) to (4) is an example of migratory insertion of carbon monoxide into the iridium-carbon bond. The active catalyst species is regenerated by the reductive elimination of acetyl iodide from (4), a de-insertion reaction.[23]

Olefin insertion

The insertion of ethylene and propylene into titanium alkyls is the cornerstone of Ziegler-Natta catalysis, the commercial route of polyethylene and polypropylene. This technology mainly involves heterogeneous catalysts, but it is widely assumed that the principles and observations on homogeneous systems are applicable to the solid-state versions. Related technologies include the Shell Higher Olefin Process which produces detergent precursors.[25] the olefin can be coordinated to the metal before insertion. Depending on the ligand density of the metal, ligand dissociation may be necessary to provide a coordination site for the olefin.[26]

Other insertion reactions in coordination chemistry

Many electrophilic oxides insert into metal carbon bonds; these include sulfur dioxide, carbon dioxide, and nitric oxide. These reactions have limited practical significance, but are of historic interest. With transition metal alkyls, these oxides behave as electrophiles and insert into the bond between metals and their relatively nucleophilic alkyl ligands. As discussed in the article on Metal sulfur dioxide complexes, the insertion of SO2 has been examined in particular detail.

References

- ^ Douglas, McDaniel, and Alexander (1994). Concepts and Models of Inorganic Chemistry 3rd Ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-471-62978-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b J.J. Alexander (1985). Hartley and Patai (ed.). The chemistry of the metal-carbon bond, vol. 2. John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Reddy, R. E.; Kowalski, C. J. (1993). "Ethyl 1-Naphthylacetate: Ester Homologation Via Ynolate Anions". Organic Syntheses. 71: 146; Collected Volumes, vol. 9, p. 426.

- ^ Arndt, F.; Eistert, B. (1935). "Ein Verfahren zur Überführung von Carbonsäuren in ihre höheren Homologen bzw. deren Derivate". Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. (in German). 68 (1): 200–208. doi:10.1002/cber.19350680142.

- ^ Ye, T.; McKervey, M. A. (1994). "Organic Synthesis with α-Diazo Carbonyl Compounds". Chem. Rev. 94 (4): 1091–1160. doi:10.1021/cr00028a010.

- ^ a b Linder, M. R.; Steurer, S.; Podlech, J. (2002). "(S)-3-(tert-Butyloxycarbonylamino)-4-phenylbutanoic acid". Organic Syntheses. 79: 154; Collected Volumes, vol. 10, p. 194.

- ^ Huggett, C.; Arnold, R. T.; Taylor, T. I. (1942). "The Mechanism of the Arndt-Eistert Reaction". J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 64 (12): 3043. doi:10.1021/ja01264a505.

- ^ Meier, H.; Zeller, K.-P. (1975). "The Wolff Rearrangement of α-Diazo Carbonyl Compounds". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 14 (1): 32–43. doi:10.1002/anie.197500321.

- ^ Kirmse, W. (2002). "100 Years of the Wolff Rearrangement". Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2002 (14): 2193–2256. doi:10.1002/1099-0690(200207)2002:14<2193::AID-EJOC2193>3.0.CO;2-D.

- ^ Clibbens, D. A.; Nierenstein, M. (1915). "The Action of Diazomethane on some Aromatic Acyl Chlorides". J. Chem. Soc., Trans. 107: 1491–1494. doi:10.1039/CT9150701491.

- ^ Bachmann, W. E.; Struve, W. S. (1942). "The Arndt-Eistert Reaction". Org. React. 1: 38.

- ^ Nierenstein, M.; Wang, D. G.; Warr, J. C. (1924). "The Action of Diazomethane on some Aromatic Acyl Chlorides II. Synthesis of Fisetol". J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 46 (11): 2551–2555. doi:10.1021/ja01676a028.

- ^ Lewis, H. H.; Nierenstein, M.; Rich, E. M. (1925). "The Action of Diazomethane on some Aromatic Acyl Chlorides III. The Mechanism of the Reaction". J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 47 (6): 1728–1732. doi:10.1021/ja01683a036.

- ^ Reed, D. D.; Bergmeier, S. C. (2007). "A Facile Synthesis of a Polyhydroxylated 2-Azabicyclo[3.2.1]octane". J. Org. Chem. 72 (3): 1024–1026. doi:10.1021/jo0619231. PMID 17253828.

- ^ Beckmann, E. (1886). "Zur Kenntniss der Isonitrosoverbindungen". Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. (in German). 19: 988–993. doi:10.1002/cber.188601901222.

- ^ Gawley, R. E. (1988). "The Beckmann Reactions: Rearrangement, Elimination-Additions, Fragmentations, and Rearrangement-Cyclizations". Org. React. 35: 14–24. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or035.01.

- ^ Eck, J. C.; Marvel, C. S. (1939). "ε-Benzoylaminocaproic acid". Organic Syntheses. 19: 20; Collected Volumes, vol. 2, 1943, p. 76.

- ^ Ritz, J.; Fuchs, H.; Kieczka, H.; Moran, W. C. (2000). "Caprolactam". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a05_031.

- ^ McMurry, J. (1988). Organic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-534-07968-7.

- ^ Blakemore, P. R.; Burge, M. S. (2007). "Iterative Stereospecific Reagent-Controlled Homologation of Pinacol Boronates by Enantioenriched-Chloroalkyllithium Reagents". J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 129 (11): 3068–3069. doi:10.1021/ja068808s.

- ^ Elschenbroich, C. ”Organometallics” (2006) Wiley-VCH: Weinheim. ISBN 978-3-527-29390-2

- ^ Hartwig, J. F. Organotransition Metal Chemistry, from Bonding to Catalysis; University Science Books: New York, 2010. ISBN 1-891389-53-X

- ^ a b c Jones, J. H. (2000). "The CativaTM Process for the Manufacture of Acetic Acid" (PDF). Platinum Metals Rev. 44 (3): 94–105.

- ^ Sunley, G. J.; Watson, D. J. (2000). "High Productivity Methanol Carbonylation Catalysis using Iridium - The CativaTM Process for the Manufacture of Acetic Acid". Catalysis Today. 58 (4): 293–307. doi:10.1016/S0920-5861(00)00263-7.

- ^ Crabtree, R. H. (2009). The Organometallic Chemistry of the Transition Metals. John Wiley and Sons. p. 19–25. ISBN 978-0-470-25762-3.

- ^ Kissin, Y. V. (2008). "Synthesis, Chemical Composition, and Structure of Transition Metal Components and Cocatalysts in Catalyst Systems for Alkene Polymerization". Alkene Polymerization Reactions with Transition Metal Catalysts. Amsterdam: Elsevier. pp. 207–290. ISBN 978-0-444-53215-2.