José Antonio Navarro

José Antonio Navarro | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal details | |

| Born | right February 27, 1795 San Antonio de Béxar, Spanish Texas, Viceroyalty of New Spain José Antonio Navarro |

| Died | January 13, 1871 San Antonio, Texas, United States 200px José Antonio Navarro |

| Resting place | right thumb 200px José Antonio Navarro |

| Nationality | Spanish (1795–1821), Mexican (1821–1836), Tejano (1836–1848) and American (1848–1871) |

| SpouseJosé Antonio Navarro | Margarita de la Garza |

| Parent |

|

| Profession | Statesman, revolutionary and merchant |

José Antonio Navarro (February 27, 1795 – January 13, 1871) was a Texas statesman, revolutionary, rancher, and merchant. The son of Ángel Navarro and Josefa María Ruiz y Peña, he was born into a distinguished noble family at San Antonio de Béxar in the Viceroyalty of New Spain (now the American city of San Antonio, Texas). His uncle was José Francisco Ruiz and his brother-in-law was Juan Martín de Veramendi.

Navarro County, Texas, established in 1846, is named in his honor, as is the small town of Navarro, Texas.[1]

Texas Patriot

Navarro was proficient in the laws of Mexico and Spain, although he is mainly self-educated.[1] A native Texan, he had a vision of the future of Texas like that of Stephen F. Austin. He and Austin developed a steady friendship. [2] Navarro and Austin worked together to found the new state of Texas.[3] An early proponent of Texas independence, he took part in the 1812–1813 Magee, Gutiérrez and Toledo resistance movements.

Working with the empresarios of the period, he helped Stephen F. Austin obtain his contracts to bring settlers into the area.[2] He became a land commissioner for Dewitt's Colony and, soon after, for the Béxar District. In 1825 Navarro married Margarita de la Garza and they raised seven children.

During the early 1830s Navarro represented Texas both in the legislature of the State of Coahuila and Texas and in the federal Congress in Mexico City.[4] Always a champion of democratic ideas, Navarro, collaborating with Austin, worked to pass legislation that would best benefit the people of Texas.[2]

Navarro later served as a leader in the Texas Revolution.[5] He was at the Convention for Texas Independence,[6] when he received the somber news from Juan Seguin, of the Alamo's fall.[7] With the death of James Bowie (his nephew by marriage), Navarro had to secure the release of the surviving Navarros, two women and a child,[8] who were being held by the Mexicans at the Músquiz house.[9] They were removed to the Navarro family home.[10] The surviving noncombatants [11] thereby avoided humiliation or death from General Antonio López de Santa Anna.[9]

José Antonio Navarro was one of the original signers of the Texas Declaration of Independence, in early March, 1836, in Washington-on-the-Brazos.[12] He later signed the Constitution of the Republic of Texas.

In 1841, Navarro reluctantly participated in the ill-conceived Texan Santa Fe Expedition sent by President Mirabeau B. Lamar, when he tried to persuade the residents of New Mexico to secede from Mexico and join with Texas.[13] He was captured, put on trial, sentenced to death, and imprisoned for years.[14] He escaped with the help of sympathetic Mexican Army officials, sailing back to Texas.[15]

José Antonio Navarro became a Representative in the Republic of Texas Congress from Bexar County, Texas. Attempting to keep a balance of power, he worked closely with Senator Juan Seguin to promote legislation favorable to the Tejano citizenry, who were quickly becoming the political minority. Education was one such priority, working to bring academic institutions into the San Antonio area.[16] He supported the annexation of Texas by the United States. In 1845 Navarro was instrumental in drafting the first state Constitution of Texas, ensuring future political rights for all peoples. He served three terms in the Texas Senate before retiring from politics in 1849.[15]

Later life

In his retirement, Navarro wrote several historical and political essays about Texas and San Antonio's role in the Mexican Independence movement for the San Antonio Ledger.

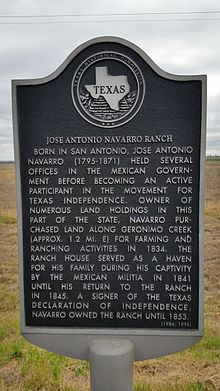

Ranching occupied much of his time in later years, and he spent most of each spring, summer, and fall on the 6,000-acre (24 km2) San Geronimo Ranch, rich grasslands near Seguin, Texas, about 35 miles east of San Antonio.[17]

Navarro later sold his ranch and lived full-time in San Antonio, where he died in 1871.

Legacy

In 1846, the Texas Legislature named Navarro County south of Dallas to honor his service. In 1848, Navarro County's seat of government was founded, and José Navarro was selected the name for the town.

A Texas State historical marker identifies his Geronimo Creek ranch in south Texas. Navarro Street In downtown San Antonio is also named for him.

Casa Navarro State Historic Site in San Antonio is the original residence complex of José Antonio Navarro. He first bought the property, about 1.5 acres, in 1832 (during the Mexican Texas period. The structures of limestone, caliche block, and adobe were built over the next twenty years or so. The site is situated in the heart of old San Antonio. The buildings were acquired and restored by the San Antonio Conservation Society; and the complex, including his one-story limestone home, kitchen, and a two-story store and offices, was opened to the public in October 1964. The site was placed on the National Register in 1972, and it is now operated by the Texas Historical Commission.

References

- ^ a b Lozano (1985), p. 30.

- ^ a b c Todish (1998), p. 107.

- ^ Tovares (2004), PBS American Experience, Remember the Alamo.

- ^ Edmonson (2000), p. 105.

- ^ Edmonson (2000), p. 38.

- ^ Matovina (1995), p. 26.

- ^ de la Teja (1991), p. 26.

- ^ Groneman (1990), pp. 5, 83.

- ^ a b Matovina (1995), p. 66.

- ^ Lord (1961), p. 176.

- ^ Todish (1998), p. 91.

- ^ Brands (2005), p. 382.

- ^ Lozano (1985), p. 31.

- ^ de la Teja (1991), p. 101.

- ^ a b Lozano (1985), p. 32.

- ^ de la Teja (1991), p. 34.

- ^ Navarro Ranch

- Brands, H.W. (2005). Lone Star Nation: The Epic Story of the Battle for Texas Independence, 1835. New York: Random House, Inc. ISBN 1-4000-3070-6.

- del la Teja, Jesus (1991). A Revolution Remembered: The Memoirs and Selected Correspondence of Juan N. Seguin. Austin, TX: State House Press. ISBN 0-938349-68-6.

- Edmondson, J.R. (2000). The Alamo Story-From History to Current Conflicts. Plano, TX: Republic of Texas Press. ISBN 1-55622-678-0.

- Groneman, Bill (1990). Alamo Defenders, A Genealogy: The People and Their Words. Austin, TX: Eakin Press. ISBN 0-89015-757-X.

- Lord, Walter (1961). A Time to Stand. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-7902-7.

- Lozano, Ruben Rendon (1985). Viva Texas: The Story of the Tejanos, the Mexican-born Patriots of the Texas Revolution. San Antonio, TX: The Alamo Press. ISBN 0-943260-02-7.

- Matovina, Timothy M. (1995). The Alamo Remembered: Tejano Accounts and Perspectives. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-75186-9.

- Poyo, Gerald Eugene (1996). Tejano journey, 1770–1850. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-76570-3.

- Todish, Timothy J.; Todish, Terry; Spring, Ted (1998). Alamo Sourcebook, 1836: A Comprehensive Guide to the Battle of the Alamo and the Texas Revolution. Austin, TX: Eakin Press. ISBN 978-1-57168-152-2.

- Tovares, Joseph (2004). Remember the Alamo. Documentary video produced by Tovares. PBS American Experience.

{{cite book}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Winders, Richard Bruce (2004). Sacrificed at the Alamo: Tragedy and Triumph in the Texas Revolution. Austin, TX: State House Press. ISBN 1-880510-81-2.

Further reading and viewing

- Lindley, Thomas Ricks (2003). Alamo Traces: New Evidence and New Conclusions. Lanham, MD: Republic of Texas Press. ISBN 1-55622-983-6.

- Ramos, Raul A. (2008). Beyond the Alamo, forging Mexican ethnicity in San Antonio, 1821–1861. NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-3207-3.

- David McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro: In Search of the American Dream in Nineteenth-Century Texas, Texas State Historical Association, 2011.

- Defending Mexican Valor in Texas: Jose Antonio Navarro's Historical Writings, 1853–1857, Jose Antonio Navarro, David R. McDonald, Timothy M. Matovina, State House Press, October 1995, ISBN 978-1-880510-31-5.

- In Storms of Fortune: The Public Life of José Antonio Navarro, written by Anastacio Bueno, M.A. thesis, University of Texas at San Antonio, 1978.

- Jose Antonio Navarro, co-creator of Texas, Baylor University Press, 1969, 127 pages, ASIN: B0006CAIBS.

- Remember the Alamo, American Experience; PBS documentary program (video recording), 2004.[1]

External links

- Biography of José Antonio Navarro, written by an Old Texan, published 1876 and hosted by the Portal to Texas History

- José Antonio Navarro from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Read Jose Antonio Navarro's entry in the Biographical Encyclopedia of Texas hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- PBS American Experience, People & Events: José Antonio Navarro (1795–1871) [2]

- 1795 births

- 1871 deaths

- People of Spanish Texas

- People of the Texas Revolution

- Texas State Senators

- People from San Antonio, Texas

- People of Texas in the American Civil War

- American people of Spanish descent

- People from Seguin, Texas

- American people of Corsican descent

- American city founders

- Navarro County, Texas