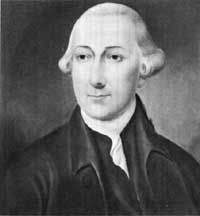

Joseph Hewes

Joseph Hewes (January 23, 1730 – November 10, 1779), was a native of Princeton, New Jersey, where he was born in 1730. Hewes’s parents were part of the Quaker Society of Friends. Immediately after their marriage they moved to New Jersey, which became Joseph Hewes’s home state. Hewes was formally educated at Princeton and after college he became an apprentice of a merchant. After finishing his apprenticeship he earned himself a good name and a strong reputation, which would serve him well in becoming one of the most famous signers of the Declaration of Independence for North Carolina, along with William Hooper and John Penn. After a few years as a successful merchant, he became very wealthy. Hewes moved to Edenton, North Carolina at the age of 30 and won over the people of the state with his charm and honorable businesslike character. Hewes was elected to the North Carolina legislature in 1763, only three years after he moved to the state. Second to the delegates of Massachusetts, Hewes was a pioneer of independence who influenced his state to be more rebellious during the years leading up to the revolution. After being re-elected numerous times in the legislature, Hewes was now focused on a new and more ambitious job as a continental congressman.

Continental Congress

By 1773, the majority of North Carolina was in favor of independence. North Carolina elected Hewes to become a representative of the Continental Congress in 1774. The people of North Carolina thought that he would best represent them because of his activism for the American cause of independence, which appealed to people in other states as well. Though the people of the United States wanted independence, Hewes found it much harder in Congress to convey his opinion without being laughed at or scolded. Even in the year leading up to the revolution, more than two-thirds of the Continental Congress still believed that ties between King George and the colonies could stay intact. Hewes was barely able to speak in Congress because he was usually interrupted by those who disagreed with him. Nevertheless he was actively involved in many committees, most of which favored the revolution. One such committee was the Committee of Correspondence, which advocated ideas that supported independence. One of the ideas that Hewes contributed to this committee was the following statement: "State the rights of the colonies in general, the several instances in which these rights are violated or infringed, and the means most proper to be pursued for obtaining a restoration of them."

Traditionally the Quakers were pacifists. Ironically, Hewes was not only one of the few people in favor of a war against Britain but was one of the few Quakers in Congress. The Quakers not only opposed war, but strongly opposed the committees that supported war too. Hewes had to break ties with the Quakers because of conflicting views thus breaking ties with the only family that he had ever known.

Secretary of the Navy

At the beginning of the year 1776, Hewes was appointed as the first ever Secretary of the Navy. John Adams often said that Hewes "laid the foundation, the cornerstone of the American Navy." Alongside General George Washington, Hewes became one of the greatest military achievers in American history. He was also involved with the secret committee of claims, which further promoted the independence of the colonies. Hewes was one of the primary reasons why North Carolina submitted to independence before any other colony. He was also one of the few reasons why the Declaration of Independence was ever signed.

Retirement

After Hewes signed the Declaration of Independence, he retreated to his home in New Jersey because of his ailing health. Despite his health problems, Hewes ran for re-election in Congress but failed to win. In 1779 he finally served his last few months as a congressman and on November 10, 1779 Joseph Hewes died right before his fiftieth birthday. All of the Continental Congress came to his funeral the following day and mourned the great loss that the country had suffered. A 1779 inventory signed by Hewes, as well as a 1780 newspaper account of his estate sale, both indicate that Hewes owned slaves. Hewes kept a diary in the last years of his life. Before he died, he wrote that he was a sad and lonely man and had never wanted to remain a bachelor. The girl he loved had died a few days before their wedding and he never married leaving no children to inherit his money and estates.

Although Hewes never had an opportunity to see the Colonies become fully recognized as the United States, he is seen somewhat as a Moses of his time in that he led his nation to independence but never saw the day that the country was free. Not many people think of Hewes as playing a vital role in the creation of our country or credit him with many of his achievements but Joseph Hewes was undoubtedly one of the most important people of his time and a true revolutionary.

Hewes was a member of Unanimity Lodge No. 7, visited in 1776, and was buried with Masonic funeral honors.