Keynesian cross

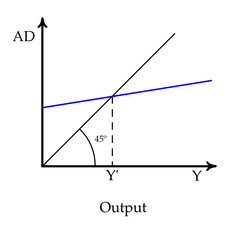

The Keynesian cross diagram demonstrates the relationship between aggregate demand (shown on the vertical axis) and real GDP (shown on the horizontal axis, measured by output).

In the Keynesian cross diagram (or 45-degree line diagram), a desired total spending (or aggregate expenditure, or "aggregate demand") curve (shown in blue) is drawn as a rising line since consumers will have a larger demand with a rise in disposable income, which increases with total national output. This increase is due to the positive relationship between consumption and consumers' disposable income in the consumption function. Aggregate demand may also rise due to increases in investment (due to the accelerator effect), while this rise is reduced if imports and tax revenues rise with income. Equilibrium in this diagram occurs where total demand, AD, equals the total amount of national output, Y, (which corresponds to total national income or production). Here, total demand equals total supply.

In the diagram, the equilibrium level of output and demand is determined where this desired spending curve intersects a line that represents the equality of total income and output (AD=Y). The intersection gives the equilibrium output, Y.

The movement toward equilibrium is mostly via changes in inventories inducing changes in production and income. If current output exceeds the equilibrium, inventories accumulate, encouraging businesses to cut back on production, moving the economy toward equilibrium. Similarly, if the level of production is below the equilibrium, then inventories run down, encouraging an increase in production and thus a move toward equilibrium. This equilibration process occurs when the equilibrium is stable, i.e., when the AD line is less steep than the AD=Y line.

The equilibrium level of output determines the equilibrium level of employment in the model. (In a dynamic view, these are connected by Okun's Law.) There is no reason within the model why the equilibrium level of employment should correspond to full employment. Bringing in other considerations may imply this correspondence, though.[citation needed]

If any of the components of aggregate demand (C + Ip + G + NX) rises at each level of income, for example because business becomes more optimistic about future profitability, that shifts the entire AD line upward. This raises equilibrium income and output. Similarly, if the elements of AD fall, that shifts the line downward and lowers equilibrium output. (The AD=Y line does not shift under the definition used here).

Assumptions

The Keynesian cross produces an equilibrium under several assumptions. First, the AD (blue) curve is positive. The AD curve is assumed to be positive because an increase in national output should lead to an increase in disposable income and, thus, an increase in consumption, which makes up a portion of aggregate demand.[1] Second, the AD curve is assumed to have a positive, vertical intercept. The AD curve must have a positive, vertical intercept to cross the AD=Y curve. If the curves do not cross, there is no equilibrium and no equilibrium output can be determined. The AD curve will have a positive, vertical intercept as long as there is some aggregated demand—from consumer spending, investment, net exports, or government spending—even if there is no national output.[1] The slope of the AD curve is steeper given a high multiplier value.[2]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Suranovic, Steven M. "Chapter 50-7: The Keynesian Cross Diagram." International Finance Theory and Policy. Last Updated on 1/20/05 http://internationalecon.com/Finance/Fch50/F50-7.php

- ^ Snowdon and Vane. Modern Macroeconomics. p. 61.

External links

- The Keynesian Cross includes an applet that demonstrates the Keynesian cross and how it responds to changes in underlying parameters

- Keynesian Cross Diagram by Fiona Maclachlan, The Wolfram Demonstrations Project.