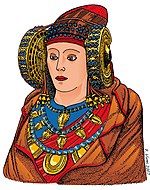

Lady of Elche

The Lady of Elche or Lady of Elx (Spanish: Dama de Elche, IPA: [ˈdama ðe ˈeltʃe]; Valencian: Dama d'Elx, IPA: [ˈdama ˈðɛʎtʃ]) is a once polychrome stone bust that was discovered by chance in 1897 at L'Alcúdia, an archaeological site on a private estate about two kilometers south of Elx/Elche, Valencia, Spain. The Lady of Elche is generally believed to be a piece of Iberian sculpture from the 4th century BC, though the artisanship suggests strong Hellenistic influences.[1] According to The Encyclopedia of Religion, the Lady of Elche (Roman Illici), is conjectured as having a direct association with Tanit, the goddess of Carthage, that was worshiped by the Punic-Iberians.[2]

Sculpture

The originally polychrome bust is usually thought to represent a woman wearing a very complex headdress and big coils on each side of the face. The aperture in the rear of the sculpture indicates it may have been used as a funerary urn.

The Lady of Guardamar is a closely similar female bust, 50 cm high, also dated circa 400 BCE, that was discovered in fragments in the Phoenecian archaeological site of Cabezo Lucero in Guardamar del Segura in Alicante province, Spain, in 1987.[3] The Lady of Guardamar has similar wheel like rodetes and necklaces.

While it is a bust, there are proposals that it was part of a seated statue like the Lady of Baza or a standing one like the Gran Dama Oferente from Cerro de los Santos (Montealegre del Castillo, Albacete). The necklaces with their pendants are closely similar to those found on the Lady of Baza, discovered about 130 miles to the south west.

The three figures and the Bicha of Balazote are exhibited in the same hall in the National Archaeological Museum of Spain in Madrid.

History

The sculpture was found in August 4, 1897 by a young worker, Manuel Campello Esclapez. This "popular" version of the story differs from the official report by Pere Ibarra (the local keeper of the records) which stated that Antonio Maciá found the bust.

Pierre Paris, a French archaeological connoisseur, purchased the sculpture within a few weeks and shipped it to France, where it was shown at the Louvre Museum and hidden for safe-keeping during World War II.

The Vichy government negotiated with Franco's government its return to Spain in 1940–41, and on June 27, 1941 the sculpture was placed in Museo del Prado (Madrid), then moved to the National Archaeological Museum, where it remains.

The discovery of the Lady of Elche initiated a popular interest in pre-Roman Iberian culture. She appeared on a 1948 Spanish one-peseta banknote and was mentioned in William Gaddis's The Recognitions (1955).

The sculpture was temporarily on display from May 18 to November 1, 2006 at the Museo Arqueológico y de Historia de Elche, where it is now represented by a replica. [4]

Claim of forgery

In 1995, John F. Moffitt, an art historian specializing in painting,[5] published Art Forgery: The Case of the Lady of Elche, University Press of Florida, in which he contended that the statue was a forgery with similarities to Symbolist art of the Belle Époque. He put forth a speculation concerning the identity of the forger and commissioner, "a physician and resident surgeon in the town of Elche" who was "well informed about the current state of Iberian studies" and owned "the fertile archaeological site of La Alcúdia".

Experts in Spanish archaeology have rejected Moffitt's theory and accept the Lady of Elche as a genuine ancient Iberian work. Antonio Uriarte of the University of Madrid has stated, "Decade by decade, research has reinforced the coherence of the Lady within the corpus of Iberian sculpture. The Lady was found more than a century ago, and many of its features, not then understood, have been confirmed by subsequent finds. For example, the use of paint in Iberian sculpture was unknown when the Lady appeared."[6] A CSIC study on the Lady of Elche's micropigmentation published in 2005 concluded that the trace pigments on the statue were consistent with ancient materials and that no modern pigments had been found.[7]

In modern culture

French artist James Tissot based figures in several of his turn-of-the-century paintings on the recently discovered Lady of Elche.[8]

See also

References

- ^ Francisco Vives Boix, La Dama de Elche en el año 2000 : Análisis tecnológico y artístico [1].

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Religion, Macmillian Library Ref. USA - Iberian Religion - page 549

- ^ [2] Historia Guardamar

- ^ Facsimile of the Dama de Elche executed by Adam Lowe's studio Factum Arte in Madrid (2002-2005)

- ^ Jack Moffitt, 1940-2008

- ^ R. Olmos and T. Tortosa, in Gocha R. Tsetskhladze (ed.), Ancient Greeks West and East, Leiden: Brill, 1999, brief summary here [3]

- ^ M. P. Luxán, J. L. Prada, F. Dorrego, 2005, "Dama de Elche: pigments, surface coating and stone of the sculpture", Materials and structures, 38(277), pp. 419-424. [4] See also [5]

- ^ Biblical Archaeology Library