Ley line

Ley lines /leɪ laɪnz/ are alignments of places of significance in the geography or culture of an area, often including man-made structures. They are in the older sense, ancient, straight trackways in the British landscape, or in the newer sense, spiritual and mystical alignments of land forms.

The phrase was coined in 1921 by the amateur archaeologist Alfred Watkins, referring to supposed alignments of numerous places of geographical and historical interest, such as ancient monuments and megaliths, natural ridge-tops and water-fords. In his books Early British Trackways and The Old Straight Track, he sought to identify ancient trackways in the British landscape. Watkins later developed theories that these alignments were created for ease of overland trekking by line-of-sight navigation during neolithic times, and had persisted in the landscape over millennia.[1]

In a book called The View Over Atlantis (1969), the writer John Michell revived the term "ley lines", associating it with spiritual and mystical theories about alignments of land forms, drawing on the Chinese concept of feng shui. He believed that a mystical network of ley lines existed across Britain.[2]

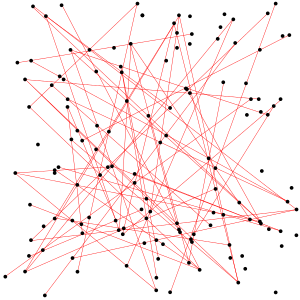

Since the publication of Michell's book, the spiritualised version of the concept has been adopted by other authors and applied to landscapes in many places around the world. Both versions of the theory have been criticised on the grounds that a random distribution of a sufficient number of points on a plane will inevitably create alignments of random points purely by chance.

Alfred Watkins and The Old Straight Track

The concept of "ley lines" originated with Alfred Watkins in his books Early British Trackways and The Old Straight Track, though Watkins also drew on earlier ideas about alignments; in particular he cited the work of the English astronomer Norman Lockyer, who argued that ancient alignments might be oriented to sunrise and sunset at solstices.[3][4]

On 30 June 1921, Alfred Watkins visited Blackwardine in Herefordshire, and had been driving along a road near the village (which has now virtually disappeared). Attracted by the nearby archaeological investigation of a Roman camp, he stopped his car to compare the landscape on either side of the road with the marked features on his much used map. While gazing at the scene around him and consulting the map, he saw, in the words of his son, "like a chain of fairy lights" a series of straight alignments of various ancient features, such as standing stones, wayside crosses, causeways, hill forts, and ancient churches on mounds.[1] He realized immediately that the potential discovery had to be checked from higher ground when, during a revelation, he noticed that many of the footpaths there seemed to connect one hilltop to another in a straight line.

He subsequently coined the term "ley" at least partly because the lines passed through places whose names contained the syllable ley, stating that philologists defined the word (spelled also as lay, lea, lee, or leigh) differently, but had misinterpreted it.[5][6][7] He believed this was the ancient name for the trackways, preserved in the modern names. The ancient surveyors who supposedly made the lines were given the name "dodmen".[1][8] Watkins believed that, in ancient times, when Britain was far more densely forested, the country was criss-crossed by a network of straight-line travel routes, with prominent features of the landscape being used as navigation points. This observation was made public at a meeting of the Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club of Hereford in September 1921.

His work referred to G. H. Piper's paper presented to the Woolhope Club in 1882, which noted that: "A line drawn from the Skirrid-fawr mountain northwards to Arthur's Stone would pass over the camp and southern most point of Hatterall Hill, Oldcastle, Longtown Castle, and Urishay and Snodhill castles."[9] It has also been suggested that Watkins' speculation (he called it 'surmise')[1] stemmed from reading an account in September 1870 by William Henry Black given to the British Archaeological Association in Hereford titled Boundaries and Landmarks, in which he speculated that "Monuments exist marking grand geometrical lines which cover the whole of Western Europe".[10] He published his book Early British Trackways the following year, commenting: "I knew nothing on June 30th last of what I now communicate, and had no theories".[11]

Examples of ley lines in Britain

Alfred Watkins theorised that St. Ann's Well in Worcestershire is the start of a ley line that passes along the ridge of the Malvern Hills through several springs including the Holy Well, Walms Well, and St. Pewtress Well.[12]

In The Ley Hunter's Companion (1979), Paul Devereux theorised that a 10-mile alignment he called the "Malvern Ley" passed through St Ann's Well, the Wyche Cutting, a section of the Shire Ditch, Midsummer Hill, Whiteleaved Oak, Redmarley D'Abitot and Pauntley.[13]

In City of Revelation (1973) British author John Michell theorised that Whiteleaved Oak is the centre of a circular alignment he called the "Circle of Perpetual Choirs" and is equidistant from Glastonbury, Stonehenge, Goring-on-Thames and Llantwit Major. The theory was investigated by the British Society of Dowsers and used as background material by Phil Rickman in his novel The Remains of an Altar (2006).[14][15]

Perhaps relevant to the ley line argument is the existence of cursuses, massive parallel imprints in the ground made by people between 3400 and 3000 BCE. Ranging in length from 50 metres to several kilometers, their exact function remains unknown though they are commonly believed to have been used for ceremonial processions. Many of them do encompass Neolithic graves and monuments. However, while some cursuses are relatively straight, others have curves and sharp turns. This may argue that ancient Britons had little interest in moving in straight lines over landscapes.[16]

Criticism

Watkins' work met with early scepticism from archaeologists, one of whom, O. G. S. Crawford, refused to accept advertisements for The Old Straight Track (1925) in the journal Antiquity.[17] Since 1989, refutations of Watkins' ideas have been generally based on mathematical methods such as statistics and shape analysis.[citation needed]

Chance alignments

One criticism of Watkins' ley line theory states that given the high density of historic and prehistoric sites in Britain and other parts of Europe, finding straight lines that "connect" sites is trivial and ascribable to coincidence. A statistical analysis of lines concluded: "the density of archaeological sites in the British landscape is so great that a line drawn through virtually anywhere will 'clip' a number of sites." [18]

Shape analysis

A study by David George Kendall used the techniques of shape analysis to examine the triangles formed by standing stones to deduce if these were often arranged in straight lines. The shape of a triangle can be represented as a point on the sphere, and the distribution of all shapes can be thought of as a distribution over the sphere. The sample distribution from the standing stones was compared with the theoretical distribution to show that the occurrence of straight lines was no more than average.[19]

Archaeologist Richard Atkinson once demonstrated this by taking the positions of telephone boxes and pointing out the existence of "telephone box leys". Thus, he argued, showed that the mere existence of such lines in a set of points does not prove that the lines are deliberate artefacts, especially since it is known that telephone boxes were not laid out in any such manner or with any such intention.[20]

New Age endorsement

In 1969, the British author John Michell, who had previously written on the subject of UFOs, published The View Over Atlantis, in which he revived Watkins' ley line theories and linked them with the Chinese concept of feng shui.[2] The book, published by Sago Press, proved popular and was reprinted in Great Britain by Garnstone Press in 1972 and Abacus in 1973, and in the United States by Ballantine Books in 1972. Gary Lachman states that The View Over Atlantis "put Glastonbury on the countercultural map."[21] Ronald Hutton described it as "almost the founding document of the modern earth mysteries movement".[22]

Michell's mingling Watkins' amateur archaeology with Chinese spiritual concepts of land-forms led to many new theories about the alignments of monuments and natural landscape features. Writers made use of Watkins' terminology in service of concepts related to dowsing and New Age beliefs, including the ideas that ley lines have spiritual power [23] or resonate a special psychic or mystical energy.[24][25] Ascribing such characteristics to ley lines has led to the term being classified as pseudoscience.[26] New Age occultists claim ley lines are sources of power or energy. According to Robert T. Carroll, there is no evidence for this belief save the usual subjective certainty based on uncontrolled observations by untutored devotees. Nevertheless, advocates claim that the alleged energy may be related to magnetic fields. None of this has been scientifically verified.[27]

In 2004, John Bruno Hare wrote:

Watkins never attributed any supernatural significance to leys; he believed that they were simply pathways that had been used for trade or ceremonial purposes, very ancient in origin, possibly dating back to the Neolithic, certainly pre-Roman. His obsession with leys was a natural outgrowth of his interest in landscape photography and love of the British countryside. He was an intensely rational person with an active intellect, and I think he would be a bit disappointed with some of the fringe aspects of ley lines today".[28]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Watkins, Alfred Watkins (1925). The old straight track: its mounds, beacons, moats, sites, and mark stones. Methuen & Co Ltd.

- ^ a b Michell, John (1969). The View Over Atlantis. Sago Press.

- ^ Ruggles, Clive L. N. (2005). Ancient astronomy: an encyclopedia of cosmologies and myth. ABC-CLIO. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-85109-477-6.

- ^ Brown, Peter Lancaster (1976). Megaliths, Myths and Men: An Introduction to Astro-Archaeology. Blandford Press. p. 221. ISBN 0-7137-0784-4.

- ^ Brown, Peter Lancaster (1976). Megaliths, Myths and Men: An Introduction to Astro-Archaeology. Blandford Press. p. 222. ISBN 0-7137-0784-4.

- ^ Ruggles, Clive L. N., page 224.

- ^ Watkins, Alfred (1922). Ley Lines: Early British Trackways, Moats, Mounds, Camps and Sites (2008 ed.). Forgotten Books. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-60506-472-7.

- ^ Williamson, T. & Bellamy, L. (1983). Ley Lines in Question. World's Work Ltd. p. 12. ISBN 0-437-19205-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Piper, G.H. (1888). Arthur's Stone, Dorstone. Transactions of the Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club 1881-82: 175-180.

- ^ Pennick, Nigel; Devereux, Paul (1989). Lines on the landscape: leys and other linear enigmas. Hale. ISBN 978-0-7090-3704-0.

- ^ Watkins, Alfred (1922). Early British Trackways, Moats, Mounds, Camps and Sites.

- ^ Watkins, Alfred (1921). Early British Trackways, Moats, Mounds, Camps and Sites.

- ^ Devereux, P. Thomson, I. (1979). The ley hunter's companion: aligned ancient sites : a new study with field guide and maps. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-01208-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Michell, John (1973). City of Revelation: On the Proportions and Symbolic Numbers of the Cosmic Temple. Sphere. ISBN 0-349-12320-9.

- ^ Rickman, Phil (2006). The Remains of an Altar (Merrily Watkins Mystery). Quercus. ISBN 1-905204-51-5. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ^ James, Peter & Thorpe, Nick (November 1999). Ancient Mysteries. pp. 316–9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shoesmith, R. (1990). Alfred Watkins: a Herefordshire Man. Woonton Almeley: Logaston Press. p. 132. ISBN 0-9510242-7-2.

- ^ Johnson, Matthew (29 December 2009). Archaeological Theory: An Introduction (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4051-0015-1. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ^ Kendall, David G. (May 1989). "A Survey of the Statistical Theory of Shape". Statistical Science. 4 (2): 87–99. doi:10.1214/ss/1177012582.

- ^ Clive L. N. Ruggles (2005). "Ley lines". Ancient astronomy: An encyclopaedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 225. ISBN 1-85109-477-6.

- ^ Lachman, Gary (2003). Turn Off Your Mind: The Mystic Sixties and the Dark Side of the Age of Aquarius. The Disinformation Company. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-9713942-3-0. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ Hill, Rosemary (2008). Stonehenge. Harvard University Press. p. 173. ISBN 9780674031326. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ Carroll, Robert P. (2003). The sceptic's dictionary: a collection of strange beliefs, amusing deceptions, and dangerous delusions. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. p. 199. ISBN 0-471-27242-6.

- ^ Cowan, David (2003). Ley Lines and Earth Energies: An Extraordinary Journey into the Earth's Natural Energy System. Adventures Unlimited Press. ISBN 1-931882-15-0.

- ^ John P. Newport, The New Age Movement and The Biblical Worldview: Conflict and Dialogue, page 304 (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1998). ISBN 0-8028-4430-8

- ^ Regal, Brian Regal. Pseudoscience: A Critical Encyclopedia. ISBN 978-0-313-35507-3.

- ^ "Ley lines". Skepdic.com.

- ^ "Early British Trackways Index". Sacred-texts.com. 17 June 2004. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

External links

- Early British Trackways at sacred-texts.com

- Ley Lines at the Skeptic's Dictionary

- Ley-lines. article by Alex Whitaker

- An excerpt from The New Ley Hunter's Guide by Paul Devereux

- Moonraking: What does it all mean?

- Finding Places of Power: Dowsing Earth Energies

- Data sources

- The Megalithic Map (which does not take a position on this issue, but does illustrate the distribution of major megaliths in the UK)

- Megalithia, a similar website with grid references for over 1,400 sites

- GENUKI Parish Database, including grid references for over 14,000 UK churches and register offices

- The Gazetteer of British Place Names with over 50,000 entries

- Ley Lines Research

- Aliens with a taste for pick 'n' mix: Woolworths stores follow uncanny geometrical patterns

- The Ley Hunter's Companion Google Earth placemark (KMZ) file based on the 1979 book by Paul Devereux (from the British Society of Dowsers).