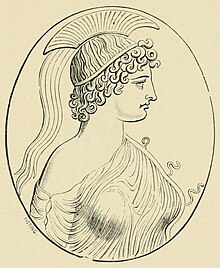

Marcia (mistress of Commodus)

Marcia Aurelia Ceionia Demetrias (died 193) was the alleged mistress (182–193) and one of the assassins of Roman Emperor Commodus. Marcia was likely to have been the daughter of Marcus Aurelius Sabinianus Euhodius, a freedman of the co-emperor Lucius Verus.[1][2]

Commodus' favourite mistress

[edit]

Before Marcia was Commodus' mistress, she was the lover and mistress of one of his cousins, Senator Marcus Ummidius Quadratus Annianus, and subsequently a wife of his servant Eclectus.[2] In AD 182, Lucilla, the sister of Commodus, convinced Marcia to join a plot with Quadratus to kill Commodus. The plot was discovered and both Lucilla and Quadratus were executed. Marcia managed to escape charges, and after Commodus' wife Bruttia Crispina was exiled and murdered for adultery, Commodus chose not to marry again and took Marcia as his concubine.[4]

Marcia had Christian sympathies and persuaded Commodus to adopt a policy favoring Christians, and kept close relations with Pope Victor I.[2] After Victor gave her a list she had asked for including all of the Christians sentenced to mines in Sardinia, she convinced Commodus to allow them to return to Rome.[2][5] Marcia was not Commodus' wife, but he was greatly influenced by her. The inscription found in Anagnia testifies that the city council decided to build a monument, commemorating her part in restoring the baths.

Assassination of Commodus

[edit]

To celebrate the Roman New Year in AD 192, Commodus decided he wanted to make an appearance before the Roman people not from the palace in traditional purple robes, but from the gladiator's barracks, escorted by the rest of the gladiators. After telling his plan to Marcia the night before, she begged him not to behave so carelessly and bring disgrace to the Roman Empire. Commodus, upset by Marcia's reaction, then told his plan to Aemilius Laetus, the Praetorian prefect, and Eclectus, his servant. After they, too, tried to dissuade him, he became furious and put their three names on a proscribed list of people to be executed the next morning, along with prominent senators.[2]

While Commodus was taking a bath, his favorite servant boy Philocommodus (whose name is a symbol of Commodus' fondness for the boy) found the tablet on which the list was written and ran into Marcia while holding the tablet.[2][6] Marcia took it from him, thinking she was protecting a document from potentially being ruined, and in horror saw her name at the top of the list. According to Herodian, she cried out, "Well done, indeed, Commodus. This is fine return for the kindness and affection I have lavished on you and for the drunken insults which I have endured from you all these years. A fuddled drunkard is not going to get the better of a sober woman".[2]

She met with Laetus and Eclectus, and the three of them decided they had to kill Commodus to save their own lives. Usually Marcia gave the emperor his first drink after his bath, so he could have the pleasure of drinking from his lover's hand. It was easy, then, for her to mix poison with the wine. After drinking the wine, he became so ill that his vomiting would not cease. The three conspirators were afraid he would vomit up all the poison, so they ordered Narcissus, a young athlete, to strangle Commodus for a large reward.

After Commodus was murdered, Marcia and Eclectus married, but she was soon killed by Didius Julianus in AD 193.[2][7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Lightman, Marjorie and Benjamin Lightman. Biographical dictionary of ancient Greek and Roman women: notable women from Sappho to Helena. New York: Facts On File, 2000, p. 157.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Krawczuk, Aleksander (2006). Poczet cesarzowych Rzymu. Warszawa: Iskry. ISBN 83-244-0021-4.

- ^ a b King, Charles William (1885). Handbook of Engraved Gems (2nd ed.). London: George Bell and Sons.

- ^ Salisbury, Joyce E. Encyclopedia of women in the ancient world. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio, 2001, pp. 205–07.

- ^ Lightman

- ^ Herodian; translated by C. R. Whittaker (1970). "1". Herodian. The Loeb Classical Library; 454–55. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 16.2–3 to 17.9–11. ISBN 0-674-99501-5.

- ^ Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony (1996). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 922.

Primary sources

[edit]- Cassius Dio, Roman history, The Loeb classical library; 454–455. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1961/69, p. 73f., 6–7. ISBN 0-674-99036-6.

- Herodian, The Loeb classical library; 454–455. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, [1969/70, 16.2-3 to 17.9-11. ISBN 0-674-99501-5.

Secondary sources

[edit]- Champlin, Edward (Summer 1979). Notes on the Heirs of Commodus. The American Journal of Philology 100: 288–306.

- Gage, J. Revue des etudes latines. Paris, France: Societe d'edition "Les belles lettres", 1923.

- Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony (1996). The Oxford classical dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 922. ISBN 978-0-19-866172-6.

- Lightman, Marjorie and Benjamin Lightman. Biographical dictionary of ancient Greek and Roman women: notable women from Sappho to Helena. New York: Facts On File, 2000. Page 157.

- Roos, A.G. (1915). Herodian's Method of Composition. The Journal of Roman Studies 5: 191–202.

- Salisbury, Joyce E. Encyclopedia of women in the ancient world. Santa Barbara, California: Abc-Clio, 2001. Pages 205–207.