Maria Rasputin

Maria Rasputin | |

|---|---|

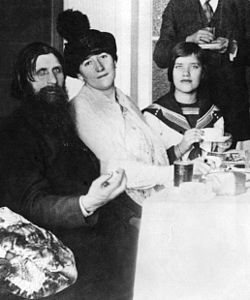

Maria Rasputina, far right, with her father, Grigori Rasputin, left, in March 1914. | |

| Born | Matryona Grigorievna Rasputina March 26,[1] 27,[2][3] or 29[4] 1898 or 1899? |

| Died | September 27, 1977 (aged 79) Los Angeles, California, United States |

| Other names | Mara, Matrena, Marochka, Maria Rasputina |

| Occupation(s) | Writer, Cabaret dancer, Circus performer, Riveter |

| Spouse(s) | Boris Soloviev (1917-1926) Gregory Bernadsky (1940-1946) |

| Children | Tatyana Solovieva Maria Solovieva |

| Parent(s) | Grigori Rasputin and Praskovia Fedorovna Dubrovina |

Maria Rasputin (baptized as Matryona Grigorievna Rasputina) 26 March 1898 – September 27, 1977 was the daughter of the Russian peasant, mystical healer Grigori Rasputin and his wife Praskovia Fyodorovna Dubrovina.

After Felix Yussupov, one of the assassins of Grigori Rasputin, published his memoir in 1928 she wrote two memoirs about her father, dealing with Tsar Nicholas II and Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna, several politicians, the scandals, the attack by Khionia Guseva and the murder. A third one, The Man Behind the Myth, was published in 1977 in association with Patte Barham. In her three memoirs, of questionable reliability,[5][6] she painted an almost saintly picture of her father, insisting that most of the negative stories were based on slander and the misinterpretation of facts by his enemies.

Early life

Matryona (or Maria) Rasputin was born in the Siberian village of Pokrovskoye, Tobolsk Governorate, on the 26th of March in 1898, but baptized the next day. Some people believe she was born in 1899; that year is also on her tombstone, but since 1990 the archives in Russia opened up and more information became available for researchers. As a teenager she came to St. Petersburg, where her first name was changed to Maria to better fit with her social aspirations.[7] Rasputin had brought Maria and her younger sister Varvara (Barbara) to live with him in the capital with the hope of turning them into "little ladies."[8] After being refused at the Smolny Institute[9] they attended Steblin-Kamensky private preparatory school in October 1913.

Her father

The little that is known about Rasputin's childhood was passed down by Maria.[11] Maria expressed her ideas about their surname, Rasputin. According to her, he was never a monk, but a starets. (As he was not an elder it is better to speak of a strannik, a pilgrim.) For Maria her father's healing practices on Tsarevich Alexei were based on magnetism.[12] According Maria, Grigory did "look into" the Khlysti's ideas.[citation needed][13]

Maria records that Rasputin was never the same man after the attack by Khioniya Guseva on 12 July [O.S. 29 June] 1914.[14][15] Maria and her mother accompanied their father to the hospital in Tyumen. After seven weeks Rasputin left the hospital and went back to St Petersburg. According to Maria her father started to drink dessert wines.[16]

On 17 December 1916 Rasputin was lured to the Moika Palace for a house warming party organized by Felix Yussupov, whom Rasputin called "The Little One."[17] (Yusupov had visited Rasputin regularly in the past few weeks or months.)[18] The following day the two sisters reported their father's missing to Anna Vyrubova. When traces of blood were detected on the parapet of the Bolshoy Petrovsky bridge on Sunday afternoon, one of Rasputin's galoshes, stuck between the bridge piles was found. Maria and her sister affirmed it belonged to their father.[19]

Maria asserts that, after the attack by Guseva, her father suffered from hyperacidity and avoided anything with sugar.[20] She and her father's former secretary, Simanotvich, doubted he was poisoned at all.[21][22] It is Maria who mentioned the homosexual advances of Felix Yusupov towards her father. According to her he was murdered when he refused this. According to Fuhrmann there is no reason to think Yusupov found Rasputin attractive.[23]

It is not clear whether Rasputin's two daughters were present at Rasputin's burial in Vyrubova's garden, next to the Alexander Palace and the surrounding park, although Maria claimed she was there.[24][25] The two sisters were invited in the Alexandra palace to play with the four grand duchesses, quite often referred to as OTMA; meanwhile Maria and her sister had moved into a smaller apartment.

Life following the Revolution

Maria was briefly engaged during World War I to a Georgian officer surnamed Pankhadze. Pankhadze had avoided being sent to the war front thanks to Rasputin's intervention and was doing his military service with the reserve battalions in Petrograd.[26]

Rasputin's followers persuaded Maria to marry Boris Soloviev, the charismatic son of Nikolai Soloviev, the Treasurer of the Holy Synod and one of her father's admirers.[27] Boris Soloviev, a graduate of a school of mysticism, quickly emerged as Rasputin's successor after the murder. Boris, who had studied Madame Blavatsky's theosophy,[28] hypnotism, attended meetings at which Rasputin's followers attempted to communicate with the dead through prayer meetings and séances.[29] Maria also attended the meetings, but later wrote in her diary that she could not understand why her father kept telling her to "love Boris" when the group spoke to him at the séances. She said she did not like Boris at all.[30] Boris was no more enthusiastic about Maria. In his own diary, he wrote that his wife was not even useful for sexual relations, because there were so many women who had bodies he found more attractive than hers.[31] In September 1917 Boris received jewels from the Tsarina to help arrange for their escape,[32] but according to Radzinsky, he kept the funds for himself. Nonetheless, she married Boris on October 5, 1917 in the chapel of the Tauride Palace. After the fall of the Russian Provisional Government the couple fled to her mother.[33] They lived in Pokrovskoye[30] and Tobolsk.

Boris turned in the officers who had come to Ekaterinburg to plan the escape of the Romanovs. Boris lost the money he had obtained from the jewels during the Russian civil war that followed.[34] Boris defrauded prominent Russian families by asking for money for a Romanov impostor to escape to China. Boris also found young women willing to masquerade as one of the grand duchesses for the benefit of the families he had defrauded.[35] (For more information on the betrayal and jewels see the account of Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden.)

Exile

Then Boris and Maria escaped to Vladivostok.[36] The White émigrés got detained by the revolutionaries; she was questioned December 26, 1919 and January 1, 1920 and let go.[37] (Maria seems to have taken dancing lessons in Berlin. In an unknown year Maria was offered a job as a cabaret dancer in Bucharest, only because of her name.[38]) Their daughter Maria Soloviev was born on 13 March 1922 at Baden, Austria.[39] They settled in Paris, where Boris worked in an automobile factory; he died of tuberculosis in July 1926. Maria found work as a governess and a waitress to support their two young daughters, Tatiana (1920-2009) and Maria (1922-1976).

After Felix Yussupov published his memoir (in 1928) detailing the death of her father, Maria sued Yussupov and Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich of Russia in a Paris court for damages of $800,000. She condemned both men as murderers and said any decent person would be disgusted by the ferocity of Rasputin's killing.[40] Maria's claim was dismissed. The French court ruled that it had no jurisdiction over a political killing that took place in Russia.[41][42][43] Maria published the first of three memoirs about Rasputin in 1929: The real Rasputin. In 1932 Rasputin, My Father was published.

In December 1934 Maria was in London. In 1935 she found work as a circus performer for Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus, based in Peru, Indiana.[44] The circus toured America and Maria acted one season as a lion tamer, billing herself as "the daughter of the famous mad monk whose feats in Russia astonished the world."[45] She was mauled by a bear in May 1935[46] but stayed with the circus until it reached Miami, Florida, where she quit before it ceased operations.[47] Maria was ordered to leave the country within 90 days, but then, in March 1940, she married Gregory Bernadsky, a childhood chum and former White Russian Army officer, in Miami.[48] In 1946 they divorced and she became a U.S. citizen. In 1947 the youngest of her daughters married in Paris the rich Gideon Walrave Boissevain (1897-1985), ministre plénipotentiaire in Greece, Chile, Israel and the Dutch ambassador to Cuba;[39][49]

She began work as a riveter, either in Miami or in a San Pedro, Los Angeles, California shipyard during World War II.[38][citation needed] Maria worked in defense plants until 1955 when she was forced to retire because of her age. After that, she supported herself by working in hospitals, giving Russian lessons, and babysitting for friends.[50]

In 1968 Maria claimed to be psychic and said Betty Ford had come to her in a dream.[38] At one point, she said she recognized Anna Anderson as Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia, a claim she would later recant.[51] Maria had two pet dogs, whom she called Youssou and Pov after Felix Yussupov.[52]

During the last years of her life, she lived in Los Angeles, living on Social Security benefits. Her home was at 3458 Larissa Drive in the Silverlake, an area of Los Angeles with Russian émigrés. As of 2013, the original home is still standing. Maria is buried in Angelus Rosedale Cemetery. Her headstone is located in Section H, Lot 189, Grave 1N, in the top center of that section.

Legacy

Maria told her grandchildren that her father taught her to be generous, even in times when she was in need herself. Rasputin said she should never leave home with empty pockets, but should always have something to give to the poor.[53] According to Maria their infamous great-grandfather was a "simple man with a big heart and strong spiritual power, who loved Russia, God, and the Tsar," her granddaughter Laurence Huot-Solovieff, the daughter of Maria's daughter Tatyana, recalled in 2005.[53]

See also

- In 1990 Patte Barham published a cookbook Peasant to Palace, based on recipes by Maria Rasputin, which includes recipes for jellied fish heads and her father's favorite, cod soup.[54]

- A fictionalized account of Maria's life appeared in the 2006 novel Rasputin's Daughter, by Robert Alexander.

- Nicholas and Alexandra: An Intimate Account of the Last of the Romanovs and the Fall of Imperial Russia

- The Spokesman-Review - Nov 18, 1967

- The Palm Beach Post - Jul 25, 1977

- "Favorite daughter of Grigori Rasputin Maria", allrussia

Notes

- ^ Fuhrmann, p. 13.

- ^ California State Death Index, Name: Maria G. Rasputin, Birth Date: 03-27-1898 [sic], Sex: Female, Death Place: Los Angeles Co. (19), Death Date: 09-27-1977, SSN: 115-09-2290, Age: 78 yrs. [sic]

- ^ U.S. Social Security Death Index, Name: Maria Bern, Birth: 27 Mar 1889, SSN: 115-09-2290, Issued: New York, Death: Sep 1977, Last Residence: 90026 (Los Angeles, Los Angeles Co., CA).

- ^ "Findagrave.com". Findagrave.com. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- ^ van der Meiden, p. 84.

- ^ Fuhrmann, p. X

- ^ Alexander, Robert, Rasputin's Daughter, Penguin Books, 2006, ISBN 978-0-14-303865-8, pp. 297-298

- ^ Edvard Radzinsky, The Rasputin File, Doubleday, 2000, ISBN 0-385-48909-9, p. 201.

- ^ Fuhrmann, p. 134.

- ^ Петербургские квартиры Распутина. Petersburg-mystic-history.info. Retrieved on 15 July 2014.

- ^ Rasputin.

- ^ Rasputin, p. 33.

- ^ Moynahan, p. 37.

- ^ Mon père Grigory Raspoutine. Mémoires et notes (par Marie Solovieff-Raspoutine) J. Povolozky & Cie. Paris 1923; Matrena Rasputina, Memoirs of The Daughter, Moscow 2001. ISBN 5-8159-0180-6 Template:Ru icon

- ^ Rasputin, p. 12.

- ^ Rasputin, p. 88.

- ^ Radzinsky, The Rasputin File, pp. 452-454

- ^ Maria Rasputin, p. 13

- ^ Radzinsky, The Rasputin File, pp. 452-454

- ^ Rasputin, pp. 12, 71, 111.

- ^ A. Simanotwitsch (1928) Rasputin. Der allmächtige Bauer. p. 37

- ^ Radzinsky (2000), p. 477.

- ^ Fuhrmann, p. 204.

- ^ Rasputin, p. 16

- ^ Fuhrmann, p. 222

- ^ Radzinsky, The Rasputin File, p. 385

- ^ http://allrus.me/favorite-daughter-grigori-rasputin-maria/

- ^ Moe, p. 628.

- ^ Robert K. Massie, Nicholas and Alexandra, Dell Publishing Co., 1967, ISBN 0-440-16358-7, p. 487

- ^ a b Massie, p. 487

- ^ Radzinsky, Edvard, The Last Tsar, Doubleday, 1992, ISBN 0-385-42371-3, p. 230

- ^ Moe, p. 628-629.

- ^ Fuhrmann, p. 233.

- ^ Radzinsky, The Rasputin File, pp. 493-494

- ^ Occleshaw, Michael, The Romanov Conspiracies: The Romanovs and the House of Windsor, Orion Publishing Group Ltd., 1993, ISBN 1-85592-518-4 p. 47

- ^ Fuhrmann, p. 235.

- ^ Forum Alexanderpalace

- ^ a b c Barry, Rey (1968). "Kind Rasputin". "The Daily Progress (Charlottesville, Virginia, USA)". Retrieved February 18, 2007.

- ^ a b http://www.thepeerage.com/p64178.htm#c641776.2

- ^ King, Greg, The Man Who Killed Rasputin, Carol Publishing Group, 1995, ISBN 0-8065-1971-1, p. 232

- ^ King, p. 233

- ^ Fuhrmann, p. 236

- ^ Moe, p. 630.

- ^ http://bucklesw.blogspot.nl/2011/05/bert-nelson-maria-rasputin-hw-peru-1935.html

- ^ Massie, p. 526

- ^ http://librarium.fr/ru/newspapers/russiaillustrated/1935/05/19/5

- ^ Women of the American Circus, 1880-1940, p. 162 by Katherine H. Adams, Michael L. Keene

- ^ Time magazine (March 4, 1940). "Milestones, Mar. 4, 1940". Time magazine. Retrieved Dec 14, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ Amsterdam City Archives

- ^ Wallechinsky, David; Wallace, Irving (1975–1981). "People's Almanac Series". "Famous Family History Grigori Rasputin Children". Retrieved February 18, 2007.

- ^ http://www.freewarehof.org/manahans.html

- ^ King, p. 277

- ^ a b Stolyarova, Galina (2005). "Rasputin's Notoriety Dismays Relative". "The St. Petersburg Times(St. Petersburg, Russia)". Retrieved February 18, 2007.

- ^ Alexander, pp. 297-298

References

- Robert Alexander, Rasputin's Daughter, Penguin Books, 2006, ISBN 978-0-14-303865-8

- Fuhrmann, Joseph T. (2013). Rasputin, the untold story (illustrated ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-1-118-17276-6.[1]

- Greg King, The Man Who Killed Rasputin, Carol Publishing Group, 1995, ISBN 0-8065-1971-1

- Robert K. Massie, Nicholas and Alexandra, 1967, Dell Publishing Co., ISBN 0-440-16358-7

- Massie, Robert K (2004) [originally in New York: Atheneum Books, 1967]. Nicholas and Alexandra: An Intimate Account of the Last of the Romanovs and the Fall of Imperial Russia (Common Reader Classic Bestseller ed.). United States: Tess Press. ISBN 1-57912-433-X. OCLC 62357914.

- Meiden, G.W. van der (1991). Raspoetin en de val van het Tsarenrijk. De Bataafsche Leeuw. ISBN 9067072788.

- Moe, Ronald C. (2011). Prelude to the Revolution: The Murder of Rasputin. Aventine Press. ISBN 1593307128.

- Moynahan, Brian (1997). Rasputin. The saint who sinned. Random House. ISBN 0306809303.

- Michael Occleshaw, The Romanov Conspiracies: The Romanovs and the House of Windsor, Orion Publishing Group Ltd., 1993, ISBN 1-85592-518-4

- Radzinsky, Edvard (2000). Rasputin: The Last Word. St Leonards, New South Wales, Australia: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-529-4. OCLC 155418190. Originally in London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Radzinsky, Edvard (2010). The Rasputin File. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-75466-0.

- Edvard Radzinsky, The Rasputin File, Doubleday, 2000, ISBN 0-385-48909-9

- Edvard Radzinsky, The Last Tsar, Doubleday, 1992, ISBN 0-385-42371-3

- Rasputin, M. (1934). My father.

- Russian women writers

- Russian memoirists

- Women memoirists

- Circus performers

- Rasputin family

- 1898 births

- 1977 deaths

- People from Tobolsk Governorate

- People from Los Angeles, California

- White Russians (movement)

- American people of Russian descent

- Animal attack victims

- Burials at Angelus-Rosedale Cemetery, Los Angeles

- American governesses

- 20th-century women

- White Russian emigrants to France

- White Russian emigrants to the United States

- White Russian emigrants to Romania

- Imperial Russian emigrants to Romania

- Imperial Russian emigrants to France

- Imperial Russian emigrants to the United States