Minkowski's theorem

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

In mathematics, Minkowski's theorem is the statement that any convex set in ℝn which is symmetric with respect to the origin and with volume greater than 2n d(L) contains a non-zero lattice point. The theorem was proved by Hermann Minkowski in 1889 and became the foundation of the branch of number theory called the geometry of numbers.

Formulation

Suppose that L is a lattice of determinant d(L) in the n-dimensional real vector space ℝn and S is a convex subset of ℝn that is symmetric with respect to the origin, meaning that if x is in S then −x is also in S. Minkowski's theorem states that if the volume of S is strictly greater than 2n d(L), then S must contain at least one lattice point other than the origin. (Since the set S is symmetric, it would then contain at least three lattice points: the origin 0 and a pair of points ±x, where x ∈ L \ 0.)

Example

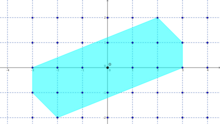

The simplest example of a lattice is the set ℤn of all points with integer coefficients; its determinant is 1. For n = 2, the theorem claims that a convex figure in the plane symmetric about the origin and with area greater than 4 encloses at least one lattice point in addition to the origin. The area bound is sharp: if S is the interior of the square with vertices (±1, ±1) then S is symmetric and convex, has area 4, but the only lattice point it contains is the origin. This observation generalizes to every dimension n.

Proof

The following argument proves Minkowski's theorem for the specific case of L = ℤ2. It can be generalized to arbitrary lattices in arbitrary dimensions.

Consider the map

Intuitively, this map cuts the plane into 2 by 2 squares, then stacks the squares on top of each other. Clearly f(S) has area less than or equal to 4. Suppose f were injective, which means the pieces of S cut out by the squares stack up in a non-overlapping way. Since f is locally area-preserving, this non-overlapping property would make it area-preserving for all of S, so the area of f(S) would be the same as that of S, which is greater than 4. That is not the case, so f is not injective, and f(p1) = f(p2) for some pair of points p1, p2 in S. Moreover, we know from the definition of f that p2 = p1 + (2i, 2j) for some integers i and j, where i and j are not both zero.

Then since S is symmetric about the origin, −p1 is also a point in S. Since S is convex, the line segment between −p1 and p2 lies entirely in S, and in particular the midpoint of that segment lies in S. In other words,

lies in S. (i,j) is a lattice point, and is not the origin since i and j are not both zero, and so we have found the point we are looking for.

Applications

An application of this theorem is the result that every class in the ideal class group of a number field K contains an integral ideal of norm not exceeding a certain bound, depending on K, called Minkowski's bound: the finiteness of the class number of an algebraic number field follows immediately.

Minkowski's theorem is also useful to prove Lagrange's four-square theorem, which states that every natural number can be written as the sum of the squares of four natural numbers.

See also

References

- Enrico Bombieri and Walter Gubler (2006). Heights in Diophantine Geometry. Cambridge U. P.

- J. W. S. Cassels. An Introduction to the Geometry of Numbers. Springer Classics in Mathematics, Springer-Verlag 1997 (reprint of 1959 and 1971 Springer-Verlag editions).

- John Horton Conway and N. J. A. Sloane, Sphere Packings, Lattices and Groups, Springer-Verlag, NY, 3rd ed., 1998.

- Hancock, Harris (1939). Development of the Minkowski Geometry of Numbers. Macmillan. (Republished in 1964 by Dover.)

- "Geometry of numbers", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Edmund Hlawka, Johannes Schoißengeier, Rudolf Taschner. Geometric and Analytic Number Theory. Universitext. Springer-Verlag, 1991.

- C. G. Lekkerkerker. Geometry of Numbers. Wolters-Noordhoff, North Holland, Wiley. 1969.

- Wolfgang M. Schmidt. Diophantine approximation. Lecture Notes in Mathematics 785. Springer. (1980 [1996 with minor corrections])

- Wolfgang M. Schmidt.Diophantine approximations and Diophantine equations, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, Springer Verlag 2000.

- Siegel, Carl Ludwig (1989). Lectures on the Geometry of Numbers. Springer-Verlag.

- Rolf Schneider, Convex bodies: the Brunn-Minkowski theory, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1993.

- "Minkowski's theorem". PlanetMath.

- Stevenhagen, Peter. Number Rings.

- Malyshev, A.V. (2001) [1994], "Minkowski theorem", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press