Moon illusion

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2008) |

The Moon illusion is an optical illusion in which the Moon appears larger near the horizon than it does while higher up in the sky. This optical illusion also occurs with the Sun and star constellations. It has been known since ancient times, and recorded by numerous different cultures. The explanation of this illusion is still debated.[1][2]

Proof of illusion

A popular belief, stretching back at least to Aristotle in the 4th century B.C., holds that the Moon appears larger near the horizon due to a real magnification effect caused by the Earth's atmosphere. This is not true: although the atmosphere does change the perceived color of the Moon, it does not magnify nor enlarge it.[3] In fact, the Moon appears about 1.5% smaller when it is near the horizon than when it is high in the sky, because it is farther away by nearly one Earth radius. Atmospheric refraction also makes the image of the Moon slightly smaller in the vertical direction. (Note that between different full moons, the Moon's angular diameter can vary from 33.5 arc minutes at perigee to 29.43 arc minutes at apogee—a difference of over 10%.[4] This is because of the ellipticity of the Moon's orbit.)

The angle that the full Moon subtends at an observer's eye can be measured directly with a theodolite to show that it remains constant as the Moon rises or sinks in the sky (discounting the very small variations due to the physical effects mentioned). Photographs of the Moon at different elevations also show that its size remains the same.[citation needed]

A simple way of demonstrating that the effect is an illusion is to hold a small object (say, 1/4 inch wide) at arm's length (25 inches) with one eye closed, positioning it next to the seemingly large Moon. When the Moon is higher in the sky, positioning the same object near the Moon reveals that there is no change in size.

Possible explanations

Refraction and distance

Ptolemy attempted to explain the Moon illusion through atmospheric refraction in the Almagest, and later (in the Optics) as an optical illusion due to apparent distance,[5][6] although interpretations of the account in the Optics are disputed.[7] In the Book of Optics (1011–1022 A.D.), Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) repeated refraction as an explanation, but also proposed an explanation based in human perception. His argument was that judging the distance of an object depends on there being an uninterrupted sequence of intervening bodies between the object and the observer; however, since there are no intervening objects between the Earth and the Moon, the observed distance is inaccurate and the Moon appears larger on the horizon.

Through additional works (by Roger Bacon, John Pecham, Witelo, and others) based on Ibn al-Haytham's explanation, the Moon illusion came to be accepted as a psychological phenomenon in the 17th century.[8].

Perception of a 'flattened sky vault'

According to Schopenhauer, the illusion is "purely intellectual or cerebral and not optical or sensuous."[9] The brain takes the sense data that is given to it from the eye and it apprehends a large moon because "our intuitively perceiving understanding regards everything that is seen in a horizontal direction as being more distant and therefore as being larger than objects that are seen in a vertical direction."[10] The brain is accustomed to seeing terrestrially–sized objects in a horizontal direction and also as they are affected by atmospheric perspective, according to Schopenhauer.

Angular size and physical size

The "size" of an object in our view can be measured either as angular size (the angle that it subtends at the eye, corresponding to the proportion of the field of vision that it occupies) or physical size (its real size measured in, say, meters). As far as human perception is concerned, these two concepts are quite distinct. For example, if two identical, familiar objects are placed at distances of five and ten meters respectively, then the more distant object subtends approximately half the angle of the nearer object, but we do not normally perceive that it is half the size. Conversely, if the more distant object did subtend the same angle as the nearer object then we would normally perceive it to be twice as big.

A central question pertaining to the Moon illusion, therefore, is whether the horizon moon appears larger because its perceived angular size seems greater, or because its perceived physical size seems greater, or some combination of both. There is currently no firm consensus on this point.

Relative size hypothesis

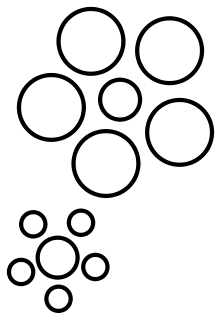

Historically, the best-known alternative to the "apparent distance" theory has been a "relative size" theory. This states that the perceived size of an object depends not only on its retinal size, but also on the size of objects in its immediate visual environment. In the case of the Moon illusion, objects in the vicinity of the horizon moon (that is, objects on or near the horizon) exhibit a fine detail that makes the Moon appear larger, while the zenith moon is surrounded by large expanses of empty sky that make it appear smaller.[11]

The effect is illustrated by the classic Ebbinghaus illusion shown at the right. The lower central circle surrounded by small circles might represent the horizon moon accompanied by objects of smaller visual extent, while the upper central circle represents the zenith moon surrounded by expanses of sky of larger visual extent. Although both central circles are actually the same size, many people think the lower one looks larger.

Angle of regard hypothesis

According to the "angle of regard" hypothesis, the Moon illusion is produced by changes in the position of the eyes in the head accompanying changes in the angle of elevation of the Moon. Though once popular, this explanation no longer has much support.[1]

Most recent research on the Moon illusion has been conducted by psychologists specializing in human perception. After reviewing the many different explanations in their 2002 book The Mystery of the Moon Illusion, Ross and Plug conclude "No single theory has emerged victorious".[12] The same conclusion is reached in the 1989 book, The Moon Illusion edited by Hershenson, which offers about 24 chapters written by different illusion researchers.

Historical references

Immanuel Kant refers to the Moon illusion in his 1781 text the Critique of Pure Reason when he writes that "the astronomer cannot prevent himself from seeing the moon larger at its rising than some time afterwards, although he is not deceived by this illusion".[13]

References

- ^ a b Hershenson, Maurice (1989). The Moon illusion. ISBN 0-8058-0121-9.

- ^ "The Moon Illusion Explained". Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ "See a huge moon illusion". USA Today. 17 June 2008.

- ^ Astronomy Picture of the Day — large and small full moons, NASA

- ^ Good, Gregory (1998). Sciences of the Earth: An Encyclopedia of Events, People, and Phenomena. Psychology Press. pp. 50–. ISBN 9780815300625. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ Robinson, J.O. (1998). The Psychology of Visual Illusion. Dover Publications. p. 55. ISBN 0486404498. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ Ross HE, Ross GM (1976). "Did Ptolemy understand the Moon illusion?". 5. Perception: 377–385.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Hershenson, Maurice (1 November 1989). The Moon Illusion. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780805801217. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason, § 21 [ist also rein intellectual oder zerebral; nicht optisch oder sensual]

- ^ On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason, § 21 [unser anschauender Verstand nach dem Horizont hin alles für entfernter, mithin für größer halt als in der senkrechten Richtung]

- ^ Restle, Frank (1970). "Moon Illusion Explained on the Basis of Relative Size". Science.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Helen Ross, Cornelis Plug (2002). The Mystery of The Moon Illusion. USA: Oxford University Press. p. 180.

- ^ Kant, Immanuel (1900). Critique of Pure Reason. Translated by J.M.D. Meiklejohn. New York: Dover Publications. p. 189.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) (B 354)

External links

- A vision scientist reviews and critiques moon illusion theories (and argues for oculomotor micropsia).

- Another careful review of moon illusion research.

- A physicist offers opinions about current theories

- Summer Moon Illusion – NASA

- Why does the moon look so big now?

- Why does the Moon appear bigger near the horizon? (from The Straight Dope)

- Moon illusion illustrated

- Moon illusion discussed at Bad Astronomy website

- New Thoughts on Understanding the Moon Illusion Carl J. Wenning, Planetarian, December 1985

- Father-Son Scientists Confirm Why Horizon Moon Appears Larger

- Astronomy Picture of the Day — 16 June 2009