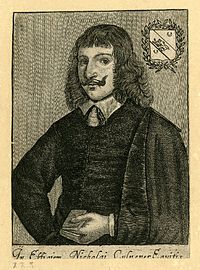

Nicholas Culpeper

Nicholas Culpeper | |

|---|---|

Nicholas Culpeper | |

| Born | 18 October 1616 |

| Died | 10 January 1654 London |

| Nationality | English |

| Known for | Complete Herbal, 1653 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | botanist herbalist physician astrologer |

| Signature | |

| |

Nicholas Culpeper (probably born at Ockley, Surrey, 18 October 1616 – died at Spitalfields, London, 10 January 1654) was an English botanist, herbalist, physician, and astrologer.[1] His published books includes The English Physitian (1652), i. e. the Complete Herbal (1653 ff), which contains a rich store of pharmaceutical and herbal knowledge, and Astrological Judgement of Diseases from the Decumbiture of the Sick (1655), which is one of the most detailed documents known on the practice of medical astrology in Early Modern Europe.

Culpeper spent the greater part of his life in the English outdoors cataloguing hundreds of medicinal herbs. He criticized what he considered the unnatural methods of his contemporaries, writing: "This not being pleasing, and less profitable to me, I consulted with my two brothers, Dr. Reason and Dr. Experience, and took a voyage to visit my mother Nature, by whose advice, together with the help of Dr. Diligence, I at last obtained my desire; and, being warned by Mr. Honesty, a stranger in our days, to publish it to the world, I have done it."[2]

Culpeper came from a long line of notable people including Thomas Culpeper, the lover of Catherine Howard (also a distant relative) who was sentenced to death by Catherine's husband, King Henry VIII.

Biography

Culpeper was the son of Nicholas Culpeper (Senior), a clergyman. Culpeper studied at Cambridge, and afterwards became apprenticed to an apothecary. After seven years his master absconded with the money paid for the indenture, and soon after this, Culpeper's mother died of breast cancer.[3] Culpeper married the daughter of a wealthy merchant, which allowed him to set up a pharmacy in the halfway house in Spitalfields, London, outside the authority of the City of London at a time when medical facilities in London were at breaking point. Arguing that "no man deserved to starve to pay an insulting, insolent physician", and obtaining his herbal supplies from the nearby countryside, Culpeper was able to provide his services for free. This, and a willingness to examine patients in person rather than simply examining their urine (in his opinion, "as much piss as the Thames might hold" did not help in diagnosis), Culpeper was extremely active, sometimes seeing as many as forty people in one morning. Using a combination of experience and astrology, Culpeper devoted himself to using herbs to treat the illnesses of his patients.

During the early months of the English Civil War he was accused of witchcraft and the Society of Apothecaries tried to rein in his practice. Alienated and radicalised he joined a trainband in August 1643 and fought at the First Battle of Newbury, where he carried out battlefield surgery. Culpeper was taken back to London after sustaining a serious chest injury from which he never recovered. There, in co-operation with the Republican astrologer William Lilly, he wrote the work 'A Prophesy of the White King', which predicted the king’s death.

He died of tuberculosis in London on 10 January 1654 at the age of 37. Only one of his eight children, Mary, survived to adulthood.

Political beliefs

Influenced during his apprenticeship by the radical preacher John Goodwin, who said no authority was above question, Culpeper became a radical republican and opposed the "closed shop" of medicine enforced by the censors of the College of Physicians. In his youth, Culpeper translated medical and herbal texts such as the 'London Pharmacopaeia' from the Latin for his master. It was during the political turmoil of the English civil war, when the College of Physicians was unable to enforce their ban on the publication of medical texts, that Culpeper deliberately chose to publish his translations in vernacular English as self-help medical guides for use by the poor who could not afford the medical help of expensive physicians. Follow-up publications included a manual on childbirth and his main work, 'The English Physician', which was deliberately sold very cheaply, eventually becoming available as far afield as colonial America. It has been in print continuously since the 17th century.

Culpeper believed medicine was a public asset rather than a commercial secret, and the prices physicians charged were far too expensive compared to the cheap and universal availability of nature's medicine. He felt the use of Latin and expensive fees charged by doctors, lawyers and priests worked to keep power and freedom from the general public.

Three kinds of people mainly disease the people – priests, physicians and lawyers – priests disease matters belonging to their souls, physicians disease matters belonging to their bodies, and lawyers disease matters belonging to their estate.

Culpeper was a radical in his time, angering his fellow physicians by condemning their greed, unwillingness to stray from Galen and their use of harmful practices such as toxic remedies and bloodletting. The Society of Apothecaries were similarly incensed by the fact that he suggested cheap herbal remedies as opposed to their expensive concoctions.[4]

Philosophy of herbalism

Culpeper attempted to make medical treatments more accessible to laypersons by educating them about maintaining their health. Ultimately his ambition was to reform the system of medicine by questioning traditional methods and knowledge and exploring new solutions for ill health. The systematisation of the use of herbals by Culpeper was a key development in the evolution of modern pharmaceuticals, most of which originally had herbal origins.[4]

Culpeper's emphasis on reason rather than tradition is reflected in the introduction to his Complete Herbal, though his definition of reason was not that different from the Romantic philosophies of the era presenting nature as refuge. He was one of the most well-known astrological botanists of his day,[5] pairing the plants and diseases with planetary influences, countering illnesses with nostroms that were paired with an opposing planetary influence. Combining remedial care with Galenic humoral philosophy and questionable astrology, he forged a strangely workable system of medicine; combined with his "Singles" forceful commentaries, Culpeper was a widely read source for medical treatment in his time.

Legacy

Culpeper's translations and approach to using herbals have had an extensive impact on medicine in early North American colonies, and even modern medications.[6] Culpeper was one of the first to translate documents discussing medicinal plants found in the Americas from Latin. His Herbal was held in such esteem that species he described were introduced into the New World from England. Culpeper described the medical use of foxglove, the botanical precursor to digitalis, used to treat heart conditions.[6] His influence is demonstrated by the existence of a chain of "Culpeper" herb and spice shops in the United Kingdom, India and beyond, and by the continued popularity of his remedies among New Age and alternative holistic medicine practitioners.[4]

Nicholas is featured as main protagonist in Rudyard Kipling's story "Doctor of Medicine", part of "Puck of Pook's Hill" series.

Examples from The English Physitian

The following herbs, their uses and preparations are discussed in The English Physitian.[4]

- Anemone, as a juice applied externally to clean ulcerations, infections and cure leprosy or inhaled to clear the nostrils.

- Bedstraw, boiled in oil and applied externally as a stimulant, consumed as an aphrodisiac, or externally raw to stimulate clotting.

- Burdock, crushed and mixed with salt, useful in treating dog bites, and taken inwardly to help pass flatulence, an analgesic for tooth pain and to strengthen the back.

- Cottonweed, boiled in lye can be used to treat head lice or infestations in cloth or clothing. Inhaled, it acts as an analgesic for headaches and reduces coughing.

- Dittany, as an abortifacient, to induce labour, as a treatment for poisoned weapons, to draw out splinters and broken bones, and the smell drives away 'venomous beasts'.

- Fleabane, helps with bites from 'venomous beasts' and its smoke can kill gnats and fleas. Can be dangerous for pregnant women.

- Hellebore, causes sneezing if ground and inhaled, kills rodents if mixed with food.

- Mugwort, induces labour, assists in birth and afterbirth and eases labour pains.

- Pennyroyal, strengthens the backs of women, assists with vertigo and helps expel gas.

- Savory, help expel gas, excellent mixed with peas and beans for this reason.

- Wood Betony, helps with 'falling sickness' and headaches, anti-anoretic, 'helps sour belchings', cramps, convulsions, bruises, afterbirth and gout, and kills worms.

Partial list of works

- A Physical Directory, or a Translation of the London Directory (1649) – translation of the Pharmacopoeia Londonesis of the Royal College of Physicians.

- Directory for Midwives (1651)

- Semeiotics Uranica, or (An Astrological Judgement of Diseases) (1651)

- Catastrophe Magnatum or (The Fall of Monarchy) (1652)

- The English Physitian (1652), later entitled The Complete Herbal[1]

- Astrological Judgement of Diseases from the Decumbiture of the Sick (1655)

- A Treatise on Aurum Potabile (1656)

See also

- Alternative medicine

- Herbalism

- Medical astrology

- History of science

- Medication

- Pharmacognosy

- List of plants in The English Physitian (1652 book)

References

Citations

- ^ a b Patrick Curry: "Culpeper, Nicholas (1616–1654)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, UK: OUP, 2004)

- ^ From the Introduction to the 1835 edition of The Complete Herbal

- ^ Scialabba, George (30 November 2004). "The Worst Medicine; book review of 'Heal Thyself: Nicholas Culpeper and the Seventeenth-Century Struggle to Bring Medicine to the People". Washington Post (online). Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- ^ a b c d Culpeper, Nicholas (2001). "The English Physician (1663) with 369 Medicines made of English Herbs; Rare book on CDROM". Herbal 1770 CDROM. Archived from the original on 14 August 2007. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- ^ Arber (2010), p. 261.

- ^ a b Sajna, Mike (9 October 1997). "Herbs have a place in modern medicine, lecturer says". University Times, 30(4), University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

Bibliography

- The English Physician Enlarged : With Three Hundred and Sixty-Nine Medicines, made of English Herbs, that were not in any impression until this. Being an astrologo-physical discourse of the vulgar herbs of this nation ... . Barker, London [1800] XML (Digital edition) pdf by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Arber, Agnes (2010) [1912]. Herbals: Their Origin and Evolution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-01671-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Culpeper, Nicholas (1995). Culpeper's Complete Herbal: A Book of Natural Remedies of Ancient Ills (The Wordsworth Collection Reference Library) (The Wordsworth Collection Reference Library). NTC/Contemporary Publishing Company. ISBN 1-85326-345-1.

- Woolley, Benjamin (2004). The herbalist: Nicholas Culpeper and the fight for medical freedom. Toronto: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-712657-3.

- Thulesius, O (December 1996). "Nicholas Culpeper, a 17th-century physician of herbal medicine: What grows in England will cure the English". Lakartidningen. 93 (51–52): 4736–7. PMID 9011726.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|laysummary=, and|laysource=(help) - McCarl, M R (1996). "Publishing the works of Nicholas Culpeper, astrological herbalist and translator of Latin medical works in seventeenth-century London". Canadian Bulletin of Medical History. 13 (2): 225–76. PMID 11620074.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|laysummary=, and|laysource=(help) - Buchanan, W (January 1995). "Nicholas Culpeper's physick for rheumatics". Clin. Rheumatol. 14 (1): 81–6. doi:10.1007/BF02208089. PMID 7743749.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|laysource=, and|laysummary=(help) - Thulesius, O (September 1994). "Nicholas Culpeper, father of English midwifery". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 87 (9): 552–6. PMC 1294777. PMID 7932467.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|laysummary=, and|laysource=(help) - Dubrow, H (1992). "Navel battles: interpreting Renaissance gynecological manuals". ANQ. 5 (2–3): 67–71. doi:10.1080/0895769x.1992.10542729. PMID 11616249.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|laysummary=, and|laysource=(help) - Bloch, H (December 1982). "Nicholas Culpeper, M.D. (1616 to 1654). Medical maverick in seventeenth-century England". New York state journal of medicine. 82 (13): 1865–7. PMID 6760002.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|laysummary=, and|laysource=(help) - Jones, D A (August 1980). "Nicholas Culpeper and his Pharmacopoeia". Pharmaceutical historian. 10 (2): 9–10. PMID 11630704.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|laysummary=, and|laysource=(help) - "The way it was. Nicholas Culpeper—the complete herbalist". Nurs. Clin. North Am. 1 (2): 344–5. June 1966. PMID 5177326.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laysource=,|laydate=, and|laysummary=(help) - "Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654)--Physician-Astrologer". JAMA. 187: 854–5. March 1964. doi:10.1001/jama.1964.03060240062020. PMID 14100140.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laysource=,|laydate=, and|laysummary=(help) - POYNTER, F N (January 1962). "Nicholas CULPEPER and his books". Jornal de historia da medicina. 17: 152–67. PMID 14037402.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|laysummary=, and|laysource=(help) - COWEN, D L (April 1956). "The Boston editions of Nicholas Culpeper". Journal of the history of medicine and allied sciences. 11 (2): 156–65. doi:10.1093/jhmas/XI.2.156. PMID 13306948.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|laysource=, and|laysummary=(help)

External links

- Nicholas Culpepper. The Complete Herbal at Project Gutenberg

- Culpeper's The English Physitian (1652) – Electronic Texts in the History of Medicine – Medical Library – Yale University

- The Complete Herbal (1653)

- This Sceptered Isle (BBC)

- Biography of Culpeper

- Culpeper's Astrologo-Physical Discourse of the Human Virtues in the Body of Man

- Opus Astrologicum, Nicholas Culpeper (PDF 2 MB)

- Directory for Midwives, Nicholas Culpeper (PDF 14,3 MB)

- Directory Astrological Judgment of Diseases, Nicholas Culpeper (PDF 8,8 MB)