Watchman (law enforcement)

A night watchman by Thomas Dekker from The Belman of London (1608). | |

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Competencies | Public safety, fire watch, crime prevention, crime detection, criminal apprehension, recovery of stolen goods |

Fields of employment | Law enforcement |

Related jobs | Thief-taker, security guard, police officer, fire lookout |

Watchmen were organised groups of men, usually authorised by a state, government, city, or society, to deter criminal activity and provide law enforcement as well as traditionally perform the services of public safety, fire watch, crime prevention, crime detection, and recovery of stolen goods. Watchmen have existed since earliest recorded times in various guises throughout the world and were generally succeeded by the emergence of formally organised professional policing.

Early origins

[edit]An early reference to a watch can be found in the Bible where the Prophet Ezekiel states that it was the duty of the watch to blow the horn and sound the alarm. (Ezekiel 33:1-6)

The Roman Empire made use of the Praetorian Guard and the Vigiles, literally the watch.

Watchmen in England

[edit]The problem of the night

[edit]The streets in London were dark and had a shortage of good quality artificial light.[1] It had been recognized for centuries that the coming of darkness to the unlit streets of a town brought a heightened threat of danger, and that the night provided cover to the disorderly and immoral, and to those bent on robbery or burglary or who in other ways threatened physical harm to people in the streets and in their houses.[2]

In the 13th century, the anxieties created by darkness gave rise to rules about who could use the streets after dark and the formation of a night watch to enforce them. These rules had for long been underpinned in London and other towns by the curfew, the time (announced by the ringing of a bell) at which the gates closed and the streets were cleared. These rules, where codified by law, would come to be known as the nightwalker statutes; such statutes empowered and required night watchmen (and their assistants) to arrest those persons found about the town or city during hours of darkness. Only people with good reason to be out could then travel through the city.[1] Anyone outside at night without reason or permission was considered suspect and potentially criminal.[3]

Allowances were usually made for people who had some social status on their side. Lord Feilding clearly expected to pass through London's streets untroubled at 1am one night in 1641, and he quickly became piqued when his coach was stopped by the watch, shouting huffily that it was a 'disgrace' to stop someone of such high standing as he, and telling the constable in charge of the watch that he would box him on the ears if he did not let his coach carry on back to his house. 'It is impossible' to 'distinguish a lord from another man by the outside of a coach', the constable said later in his defence, 'especially at unreasonable times'.[4]

Formation of watchmen

[edit]The Ordinance of 1233 required the appointment of watchmen.[5][6] The Assize of Arms of 1252, which required the appointment of constables to summon men to arms, quell breaches of the peace, and to deliver offenders to the sheriff, is cited as one of the earliest creations of an English police force, as was the Statute of Winchester of 1285.[7][8][9] In 1252 a royal writ established a watch and ward with royal officers appointed as shire reeves:

By order of the King of England the Winchester Act Mandating The Watch. Part Four and the King commandth that from henceforth all Watches be made as it hath been used in past times that was to wit from the day of Ascension unto the day of St. Michael[10] in every city by six men at every gate in every borough by twelve men in every town by six or four according to the number of inhabitants of the town. They shall keep the Watch all night from sun setting unto sun rising. And if any stranger do pass them by them he shall be arrested until morning and if no suspicion be found he shall go quit.

Later in 1279 King Edward I formed a special guard of 20 sergeants at arms who carried decorated battle maces as a badge of office. By 1415 a watch was appointed to the Parliament of England and in 1485 King Henry VII established a household watch that became known as the Beefeaters.

As of the 1660s, it was already common practice to avoid night-time service in the watch by paying for a substitute. Substitution had become so common by the late 17th century that the night watch was virtually by then a fully paid force.[11]

An act of Common Council, known as 'Robinson's Act' from the name of the sitting lord mayor, was promulgated in October 1663. It confirmed the duty of all householders in the City to take their turn at watching in order 'to keep the peace and apprehend night-walkers, malefactors and suspected persons'. For the most part the act of Common Council of 1663 reiterated the rules and obligations that had long existed. The number of watchmen required for each ward, it declared, was to be the number 'established by custom' – in fact, by an act of Common Council of 1621. Even though it had been true before the civil war that the watch had already become a body of paid men, supported by what were in effect the fines collected from those with an obligation to serve, the Common Council did not acknowledge this in the confirming act of Common Council of 1663.[12]

The act of Common Council of 1663 confirmed that watch on its old foundations, and left its effective management to the ward authorities. The important matter to be arranged in the wards was who was going to serve and on what basis. How the money was to be collected to support a force of paid constables, and by whom, were crucial issues. The 1663 act of Common Council left it to the ward beadle or a constable and it seems to have been increasingly the case that rather than individuals paying directly for a substitute, when their turn came to serve, the eligible householders were asked to contribute to a watch fund that supported hired man.[13]

From the mid-1690s the City authorities made several attempts to replace Robinson's Act and establish the watch on a new footing. Though they did not say it directly, the overwhelming requirement was to get quotas adjusted to reflect the reality that the watch consisted of hired men rather than citizens doing their civic duty—the assumption upon which the 1663 act of Common Council, and all previous acts, had been based.[14]

The implications and consequences of changes in the watch were worked out in practice and in legislation in two stages between the Restoration and the middle decades of the 18th century. The first involved the gradual recognition that a paid (and full-time) watch needed to be differently constituted from one made up of unpaid citizens, a point accepted in practice in legislation passed by the Common Council in 1705, though it was not articulated in as direct a way.[15]

The fact that the 1705 act of Common Council called for watchmen to be strong and able-bodied men seems further confirmation that the watch was now expected to be made up of hired hands rather than every male house holder serving in turn. The act of Common Council of 1705 laid out the new quotas of watchmen and the disposition of watch-stands agreed to each ward. To discourage the corruption that had been blamed for earlier under-manning, it forbade constables to collect and disturbs the money paid in for hired watchmen: that was now supposed to be the responsibility of the deputy and common councilmen of the ward.[16]

The second stage was the recognition that watchmen could not be sustained without a major shift in the way local services were financed. This led to the City's acquisition of taxing power by means of an act of Parliament[which?] in 1737 which changed the obligation to serve in person into an obligation to pay to support a force of salaried men.[15] Under the new act, the ward authorities also continued to hire their own watchmen and to make whatever local rules seemed appropriate—establishing, for example, the places in their wards where the watchmen would stand and the beats they would patrol. But the implementation of the new Watch Act did have the effect of imposing some uniformity on the watch over the whole City, making in the process some modest incursions into the local autonomy of the wards. One of the leading elements in the regime that emerged from the implementation of the new act was an agreement that every watchman would be paid the same amount and that the wages should be raised to thirteen pounds a year.[17]

From 1485 to the 1820s, in the absence of a police force, it was the parish-based watchmen who were responsible for keeping order in London's streets.[1]

Duties

[edit]Night watchmen patrolled the streets from 9 or 10 pm until sunrise, and were expected to examine all suspicious characters.[18] These controls continued in the late 17th century. Guarding the streets to prevent crime, to watch out for fires, and – despite the absence of a formal curfew – to ensure that suspicious and unauthorised people did not prowl around under cover of darkness was still the duty of night watch and the constables who were supposed to command them.[19]

The principal task of the watch in 1660 and for long after continued to be the control of the streets at night imposing a form of moral or social curfew that aimed to prevent those without legitimate reason to be abroad from wandering the streets at night. That task was becoming increasingly difficult in the 17th century because of the growth of the population and variety of ways in which the social and cultural life was being transformed. The shape of the urban day was being altered after the Restoration by the development of shops, taverns and coffee-houses, theatres, the opera and other places of entertainment. All these places remained open in the evening and extended their hours of business and pleasure into the night.[20]

The watch was affected by this changing urban world since policing the night streets become more complicated when larger number of people were moving around. And what was frequently thought to be poor quality of the watchman—and in time, the lack of effective lighting—came commonly to be blamed when street crimes and night-time disorders seemed to be growing out of control.[20]

Traditionally, householders served in the office of constable by appointment or rotation. During their year of office they performed their duties part-time alongside their normal employment. Similarly, householders were expected to serve by rotation on the nightly watch. From the late seventeenth century, however, many householders avoided these obligations by hiring deputies to serve in their place. As this practice increased, some men were able to make a living out of acting as deputy constables or as paid night watchmen. In the case of the watch, this procedure was formalized in many parts of London by the passage of "Watch Acts", which replaced householders' duty of service by a tax levied specifically for the purpose of hiring full-time watchmen. Some voluntary prosecution societies also hired men to patrol their areas.[18]

Reputation

[edit]While the societies for the reformation of manners showed there was a good deal of support for the effective policing of morality, they also suggested that the existing mechanisms of crime control were regarded by some as ineffective.[21]

Constable Dogberry's men from Much Ado About Nothing by Shakespeare, who would 'rather sleep than talk', may be dismissed as merely a dramatic device or a caricature, but successful dramatists nevertheless work with characters who strike a chord with their audience. A hundred years later such complaints were still commonplace. Daniel Defoe wrote four pamphlets and a broadsheet on the issue of street crime in which, among other things, he roundly attacked the efficacy of the watch and called for measures to ensure it 'be compos'd of stout, able-body'd Men, and of those a sufficient Number'.[22]

Watchmen on roads leading to London had a reputation for clumsiness in the late 1580s. It was a temptation on cold winter nights to slip away early from watching stations to catch some sleep. Constables in charge sometimes let watches go home early. 'The late placing and early dischargering' of night-watches concerned Common Council in 1609 and again three decades later when someone sent out to spy on watches reported that they 'break up longe before they ought'. 'The greatest parte of constables' broke up watches 'earlie in the morninge' at exactly the time 'when most danger' was 'feared' in the long night, leaving the dark streets to thieves.[23]

Watchmen often counted off the hours until sunrise on chilly nights. Alehouses offered some warmth, even after curfew bells told people to drink up. A group of watchmen sneaked into a 'vitlers' house one night in 1617 and stayed 'drinking and taking tobacco all night longe'.[24] Like other officers, watchmen could become the focus for trouble themselves, adding to the hullabaloo at night instead of ordering others to keep the noise down and go to bed. And as by day, there were more than a few crooked officers policing the streets at night, quite happy to turn a blind eye to trouble for a bribe. Watchman Edward Gardener was taken before the recorder with 'a common nightwalker' – Mary Taylor – in 1641 after he 'tooke 2s to lett' her 'escape' when he was escorting her to Bridewell late at night. Another watchman from over the river in Southwark took advantage of the tricky situation people suddenly found themselves in if they stumbled into the watch, 'demanding money [from them] for passing the watch'.[24]

A common complaint in the 1690s was that watchmen were inadequately armed. This was another aspect of the watch in the process of being transformed. The Common Council acts required watchmen to carry halberds, with some still doing so through the late seventeenth century. But it seems clear that few did, because the halberd was no longer suitable for the work they were being called upon to do. It was more often observed that watchmen failed to carry them, and it is surely the case that the halberd was no longer a useful weapon for a watch that was supposed to be mobile. By the second quarter of the 18th century, watchmen were equipped with a staff, along with their lantern.[25]

Watch houses

[edit]

Another step in the evolution of the watch involved building 'watch howses' as the country lurched towards revolution after 1640. A City committee was asked to look into the question 'what watchhouses are necessary' and where 'for the safety of this cittye' in 1642. Workmen began building watch houses in strategic spots soon after. They provided assembly-points for watchmen to gather to hear orders for the night ahead, somewhere to shelter from 'extremitye of wind and weather', and holding-places for suspects until morning when justices examined the night's catch. There were watch houses next to Temple Bar (1648), 'neere the Granaryes' by Bridewell (1648), 'neere Moregate' (1648), and next to St. Paul's south door (1649). They were not big; the one on St. Paul's side was 'a small house or shed'. This was a time of experimentation, and people (including those in authority) were learning how to make best use of these new structures in their midst.[26]

Policing the night streets

[edit]The watchmen patrolled the streets at night, calling out the hour, keeping a lookout for fires, checking that doors were locked and ensuring that drunks and other vagrants were delivered to the watch constable.[27] However, their low wages and the uncongenial nature of the job attracted a fairly low standard of person, and they acquired a possibly exaggerated reputation for being old, ineffectual, feeble, drunk or asleep on the job.[28]

London had a system of night policing in place before 1660, although it was improved over the next century through better lighting, administrations, finances, and better and more regular salaries. But the essential elements of the night-watch were performing completely by the middle of the seventeenth century.[29]

During the 1820s, mounting crime levels and increasing political and industrial disorder prompted calls for reform, led by Sir Robert Peel, which culminated in the demise of the watchmen and their replacement by a uniformed metropolitan police force.[30][31]

John Gray, the owner of Greyfriars Bobby, was a nightwatchman in the 1850s.[32]

Watchmen around the world

[edit]United States of America

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2020) |

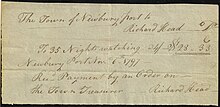

The first form of societal protection in the United States was based on practices developed in England. The City of Boston was the first settlement in the thirteen colonies to establish a night watch in 1631[33] (replaced in 1838); Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1633 (replaced in 1861);[34] New York (then New Amsterdam) (replaced in 1845) and Jamestown followed in 1658.

With the unification of laws and centralization of state power (e.g. the Municipal Police Act of 1844 in New York City, United States), such formations became increasingly incorporated into state-run police forces (see metropolitan police and municipal police).

Philippines

[edit]In the Philippines, Barangay watchmen called "Tanod" is common. Their role is to serve as frontline law enforcement officers in Barangays, especially those far from city or town centres. They are mainly supervised by the Barangay Captain and may be armed with bolo knife. [35]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Beattie, J. M. (2001). Policing and Punishment in London 1660–1750. Oxford University Press. p. 169. ISBN 0-19-820867-7.

- ^ Beattie, J.M. (2001). Policing and Punishment in London in 1660–1750. Great Britain: Oxford University Press. p. 169. ISBN 0-19-820867-7.

- ^ Griffiths, Paul (2010). Lost Londons Change, Crime, and Control in the Capital City, 1550–1660. Cambridge University Press. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-521-17411-4.

- ^ Griffiths, Paul (2010). Lost Londons Change, Crime and Control in the Capital City, 1550–1660. Cambridge University Press. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-521-17411-4.

- ^ Pollock, Frederick; Maitland, Frederic William (1898). The History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I. Vol. 1 (2 ed.). The Lawbook Exchange. p. 565. ISBN 978-1-58477-718-2.

- ^ Rich, Robert M. (1977). Essays on the Theory and Practice of Criminal Justice. University Press of America. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8191-0235-5.

The origin of the exception goes back in English history to the Ordinance of 1233 which instituted night-watchmen, and directed them 'to arrest those who enter vills at night and go about armed.' Later the Ordinance of 1252 mentions 'disturbers of our peace.'

- ^ Clarkson, Charles Tempest; Richardson, J. Hall (1889). Police!. Garland Pub. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9780824062163. OCLC 60726408.

- ^ Delbrück, Hans (1990). Renfroe, Walter J. Jr (ed.). Medieval Warfare. History of the Art of War. Vol. 3. p. 177. ISBN 0-8032-6585-9.

- ^ Critchley, Thomas Alan (1978). A History of Police in England and Wales.

The Statute of Winchester was the only general public measure of any consequence enacted to regulate the policing of the country between the Norman Conquest and the Metropolitan Police Act, 1829…

- ^ That is, from the Thursday 39 days after Easter Sunday to the 29th of September.

- ^ Beattie, J. M. (2001). Policing and Punishment in London 1660'1750. Great Britain: Oxford University Press. p. 172. ISBN 0-19-820867-7.

- ^ Beattie, J. M. (2001). Policing and Punishment in London in 1660–1750. Great Britain: Oxford University Press. p. 175. ISBN 0-19-820867-7.

- ^ Beattie, J. M. (2001). Policing and Punishment in London in 1660–1750. Great Britain: Oxford University Press. p. 177. ISBN 0-19-820867-7.

- ^ Beattie, J. M. (2001). Policing and Punishment in London in 1660–1750. Great Brirain: Oxford University Press. p. 182. ISBN 0-19-820867-7.

- ^ a b Beattie, J. M. (2001). Policing and Punishment in London in 1660–1750. Great Britain: Oxford University Press. p. 173. ISBN 0-19-820867-7.

- ^ Beattie, J. M. (2001). Policing and Punishment in London in 1660–1750. Great Britain: Oxford University Press. p. 186. ISBN 0-19-820867-7.

- ^ Beattie, J. M. (2001). Policing and Punishment in London in 1660–1750. Great Britain: Oxford University Press. p. 196. ISBN 0-19-820867-7.

- ^ a b "Constables and the Night Watch". oldbaileyonline.org.

- ^ Beattie, J. M. (2001). Policing and Punishment in London 1660-1750. Great Britain: Oxford University Press. p. 170. ISBN 0198208677.

- ^ a b Beattie, J. M. (2001). Policing and Punishment in London in 1660-1750. Great Britain: Oxford University Press. p. 172. ISBN 0198208677.

- ^ Rawlings, Philip (2002). Policing A Short History. USA: Willan Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 1-903240-26-3.

- ^ Rawlings, Philip (2002). Policing A Short History. USA: Willan Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 1-903240-26-3.

- ^ Griffiths, Paul (2010). Lost Londons Change, Crime, and Control in the Capital City, 1550–1660. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 354–355. ISBN 978-0-521-17411-4.

- ^ a b Griffiths, Paul (2010). Lost Londons Change, Crime, and Control in the Capital City, 1550–1660. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-521-17411-4.

- ^ Beattie, J. M. (2001). Policing and Punishment in London in 1660–1750. Great Britain: Oxford University Press. p. 181. ISBN 0-19-820867-7.

- ^ Griffiths, Paul (2010). Lost Londons Change, Crime, and Control in the Capital City, 1550–1660. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 359. ISBN 978-0-521-17411-4.

- ^ A. Roger Ekirch, At Day’s Close: A History of Nighttime, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2001

- ^ Philip McCouat, "Watchmen, goldfinders and the plague bearers of the night", Journal of Art in Society, http://www.artinsociety.com/watchmen-goldfinders-and-the-plague-bearers-of-the-night.html

- ^ Griffiths, Paul (2010). Lost Londons Change, Crime, and Control in the Capital City, 1550-1660. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 359. ISBN 9780521174114.

- ^ Philip Rawlings, Policing: A Short History, Willan Publishing, 2002

- ^ McCouat, op. cit.

- ^ "Touching tribute to Greyfriars Bobby and Edinburgh watchman John Gray hosted at Greyfriars Kirkyard". Edinburgh Evening News. 15 January 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ "National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund - Facts and Figures - Important Dates in Police History". www.nleomf.com. Archived from the original on 2004-10-24.

- ^ Plymouth Police History

- ^ "Seach [sic] for Outstanding Barangay Tanod". Local Government Regional Resource Center Region VI, Dept. of Interior and Local Government. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

^ This can be verified by England's Old Bailey court records.

Further reading

[edit]- David Barrie, Police in the Age of Improvement: Police Development and the Civic Tradition in Scotland, 1775-1865, Willan Publishing, 2008, ISBN 1-84392-266-5. Chapter "Watching and Warding", Google Print, p.34-41

- Second Thoughts are Best

- Augusta Triumphans

Bibliography

[edit]- Beattie, J. M. (2001). Policing and Punishment in London 1660-1750. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820867-7

- Ekirch A. R. (2001). At Day’s Close: A History of Nighttime, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Clarkson, Charles Tempest; Richardson, J. Hall (1889). Police!. OCLC 60726408

- "Constables and the Night Watch". .oldbaileyonline,retrieved 22 November 2015, http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/static/Policing.jsp

- Critchley, Thomas Alan (1978). A History of Police in England and Wales.

- Griffiths, Paul (2010). Lost Londons Change, Crime, and Control in the Capital City, 1550-1660. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521174114.

- Delbrück, Hans (1990). Renfroe, Walter J. Jr, ed. Medieval Warfare. History of the Art of War 3. ISBN 0-8032-6585-9.

- Philip McCouat, "Watchmen, goldfinders and the plague bearers of the night", Journal of Art in Society, retrieved 22 October 2015, http://www.artinsociety.com/watchmen-goldfinders-and-the-plague-bearers-of-the-night.html

- Pollock, Frederick; Maitland, Frederic William (1898). The History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I. 1 (2 ed.). ISBN 978-1-58477-718-2.

- Rawlings, Philip (2002). Policing A Short History. USA: Willan Publishing. ISBN 1903240263.

- Rich, Robert M. (1977). Essays on the Theory and Practice of Criminal Justice. ISBN 978-0-8191-0235-5.