Northern Command (RAAF)

| Northern Command | |

|---|---|

The RAAF's wartime area commands: originally to have been called Northern Area, Northern Command was formed in April 1944, re-designated Northern Area in December 1945, and disbanded in February 1947. | |

| Active | 1944–47 |

| Allegiance | Australia |

| Branch | Royal Australian Air Force |

| Role | Air defence Aerial reconnaissance Protection of adjacent sea lanes |

| Garrison/HQ | Milne Bay (1944) Madang (1944–46) Port Moresby (1946–47) |

| Engagements | World War II |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Frank Lukis (1944–45) Allan Walters (1945–46) |

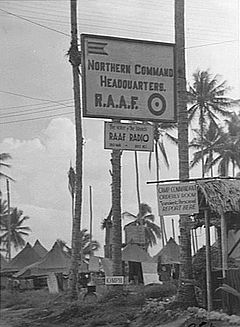

Northern Command was one of several geographically based commands raised by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) during World War II. Established in April 1944, it evolved from No. 9 Operational Group, which had been the RAAF's primary mobile formation in the South West Pacific theatre since September 1942, but had lately become a garrison force in New Guinea. Northern Command was headquartered initially at Milne Bay and then, from August 1944, in Madang. It conducted operations in New Guinea, New Britain, and Bougainville until the end of the war. Re-designated Northern Area in December 1945, it was headquartered in Port Moresby from March 1946 and disbanded in February 1947.

History

[edit]

Prior to World War II, the Royal Australian Air Force was small enough for all its elements to be directly controlled by RAAF Headquarters in Melbourne. When war broke out, the RAAF began to decentralise its command structure, commensurate with expected increases in manpower and units.[1][2] Between March 1940 and May 1941, Australia and Papua were divided into four geographically based command-and-control zones: Central Area, Southern Area, Western Area, and Northern Area.[3] The roles of the area commands were air defence, protection of adjacent sea lanes, and aerial reconnaissance. Each was led by an Air Officer Commanding (AOC) who controlled the administration and operations of air bases and units within his boundary.[2][3] By mid-1942, Central Area had been dissolved, Northern Area had been split into North-Eastern Area and North-Western Area, and Eastern Area was created, making a total of five commands.[4][5]

The static area command system was well suited to defence, but less so for an offensive posture. In September 1942, therefore, the Air Force created a large mobile formation known as No. 9 Operational Group, to act as a self-contained tactical air force that would be able to keep pace with Allied advances through the South West Pacific theatre. By September 1943, No. 9 Group had become a static garrison force in New Guinea, similar to the area commands on mainland Australia, and a new mobile group was required to support the advance north towards the Philippines and Japan. This was formed in November 1943 as No. 10 Operational Group (later the Australian First Tactical Air Force), which initially came under No. 9 Group's control. To better reflect No. 9 Group's new status, the head of RAAF Command, Air Vice Marshal William Bostock, recommended renaming it Northern Area. RAAF Headquarters did not agree to this at first, but on 11 April 1944 settled on calling it Northern Command, under the same AOC who commanded No. 9 Group, Air Commodore Frank Lukis.[6][7] On its formation the command was headquartered at Milne Bay.[8]

By July 1944, No. 10 Group's position in western New Guinea was complicating Northern Command's efforts to supply it, and the group was made independent of the command.[9] The next month, Northern Command headquarters transferred to Madang.[8] In September, No. 71 Wing was detached from No. 10 Group to Northern Command, which had been given the task of supporting the Australian 6th Division in the Aitape–Wewak campaign. Headquartered at Tadji in northern New Guinea, No. 71 Wing comprised Nos. 7, 8 and 100 Bristol Beaufort Squadrons, augmented by a flight of CAC Boomerangs from No. 4 (Army Cooperation) Squadron.[8][10] No. 74 (Composite) Wing, which had been formed in August 1943 and was headquartered at Port Moresby, also came under the aegis of Northern Command.[8][11] The command's other major operational formation was No. 84 (Army Cooperation) Wing, which began moving from Australia to Torokina on Bougainville in October 1944.[11][12] By this time, Northern Command controlled six squadrons in the New Guinea area. No. 79 Wing, equipped with B-25 Mitchells, was earmarked for transfer from North-Western Area to Northern Command, to undertake operations in New Britain, but its proposed airfield was not ready and it was instead transferred to the First Tactical Air Force at Labuan the following year.[13][14]

Air Commodore Allan Walters took over Northern Command from Lukis in February 1945.[15][16] Walters directed operations in New Guinea, New Britain and Bougainville until the end of hostilities.[17][18] Group Captain Val Hancock assumed command of No. 71 Wing in April. To maximize support to Australian ground troops in the lead-up to the final assault on Wewak, the wing's three extant Beaufort squadrons were joined by two more, Nos. 6 and 15. Approximately sixty Beauforts and Boomerangs struck Japanese positions behind Dove Bay prior to amphibious landings on 11 May to cut off retreating enemy troops. Over the entire month, the wing dropped more than 1,200 tons of bombs and flew in excess of 1,400 sorties. The wing suffered fuel and ordnance shortages; at one stage its squadrons had to load their Beauforts with captured Japanese bombs.[19] No. 84 Wing, commanded by Group Captain Bill Hely and comprising No. 5 (Tactical Reconnaissance) Squadron, flying mainly Boomerangs, and two reconnaissance and transport units, also suffered shortages of equipment, as well as pilots. Augmented by a detachment of No. 36 Squadron, flying C-47 Dakotas, its aircraft flew slightly over 4,000 sorties during the Bougainville campaign up to the end of June 1945.[20] That month, Northern Command was tasked with acting in reserve for Operation Oboe Six, the invasion of Labuan.[21] In July, No. 11 Group was formed as a "static command" headquartered on Morotai in the Dutch East Indies, using elements of Northern Command and the First Tactical Air Force; this freed the latter from garrison duties while its combat units advanced towards Borneo.[22][23]

No. 71 Wing continued operations until the last day of the Pacific War, flying its final mission involving thirty Beauforts only hours before news arrived of the Allied victory on 15 August 1945.[19] No. 74 Wing was disbanded in Port Moresby the same day.[8] No. 71 Wing squadrons subsequently dropped leaflets to remaining pockets of Japanese resistance, making them aware of the surrender; the wing was disbanded at Tadji in January 1946.[8][19] No. 84 Wing suffered morale problems following the end of the war owing to inactivity and the uncertainties of demobilisation; as a result, the wing's commanding officer sent Northern Command headquarters a frank report, its tone earning a rebuke from Walters.[20][24] No. 84 Wing left Bougainville in February 1946 and disbanded in Melbourne the next month.[8]

Northern Command was redesignated Northern Area on 1 December 1945, and its headquarters transferred to Port Moresby in March the following year.[8] Walters handed over command in June 1946.[18][25] The area headquarters was disbanded at Port Moresby on 27 February 1947.[8]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 111–112

- ^ a b "Organising for War: The RAAF Air Campaigns in the Pacific". Pathfinder. No. 121. Air Power Development Centre. October 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ a b Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 91–92 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force, pp. xx–xxi

- ^ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, p. 478 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 144, 168

- ^ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 182, 200

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Order of Battle – Air Force – Headquarters". Department of Veterans' Affairs. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, p. 242

- ^ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 335–338

- ^ a b "Governor will lead march". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney. 22 April 1950. p. 3. Retrieved 2 May 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, p. 318

- ^ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, p. 299

- ^ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, p. 334

- ^ Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force!, p. 295

- ^ "Awards for Victorians in RAAF". The Argus. Melbourne. 27 June 1946. p. 6. Retrieved 2 May 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force!, p. 304

- ^ a b Funnell, Ray. "Walters, Allan Leslie (1905–1968)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ a b c Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 342–348

- ^ a b Odgers, Air War Against Japan, p. 326

- ^ Waters, Oboe, p.74

- ^ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, p. 478

- ^ Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force, p. xxiii

- ^ No. 84 (Army Co-operation) Wing. "Operations record book". National Archives of Australia. pp. 21–23. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "High RAAF appointment". The Forbes Advocate. Forbes, New South Wales. 2 April 1948. p. 7. Retrieved 2 May 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

References

[edit]- Ashworth, Norman (2000). How Not to Run an Air Force. Canberra: RAAF Air Power Studies Centre. ISBN 064226550X.

- Gillison, Douglas (1962). Australia in the War of 1939–1945: Series Three (Air) Volume I – Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 2000369.

- Odgers, George (1968) [1957]. Australia in the War of 1939–1945: Series Three (Air) Volume II – Air War Against Japan 1943–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 1990609.

- Stephens, Alan (2006) [2001]. The Royal Australian Air Force: A History. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-555541-4.

- Waters, Gary (1995). Oboe – Air Operations Over Borneo 1945. Canberra: Air Power Studies Centre. ISBN 0-642-22590-7.