Orville E. Babcock

Orville Elias Babcock | |

|---|---|

Orville E. Babcock | |

| Born | December 25, 1835 Franklin, Vermont |

| Died | June 2, 1884 (aged 48) Mosquito Inlet, Florida |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Service | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1861 - 1884 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | United States Army Corps of Engineers |

| Battles / wars | American Civil War: |

| Other work | Private Secretary for President Ulysses S. Grant (1869-1877) |

Orville Elias Babcock (December 25, 1835 – June 2, 1884) was an American Civil War General in the Union Army. He graduated third in his class at the United States Military Academy in 1861. Babcock served in the Corps of Engineers throughout the Civil War. He was promoted to Brevet Brigadier General in 1865. Babcock served as aide-de-camp for Lieut. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and participated in the Overland Campaign. After Grant became President in 1869, Babcock was appointed his Private Secretary—in modern terms, the chief of staff—and served until 1876. Upon his appointment Babcock was young and ambitious and considered the Iago of the Grant administration. In 1869, Babcock was sent on a mission by President Grant to explore the possibility of annexing to the United States the Hispanic and mostly mulatto island nation of Santo Domingo.

Babcock's tenure under President Grant was filled with controversy concerning involvement with the manipulation of both cabinet departments and appointments. Grant supported Babcock when he was accused of corruption. Grant's shielding of Babcock from political attack stemmed primarily from their shared experiences on the battlefield during the American Civil War.[1] Indicted in the Whiskey Ring, Babcock was defended by President Grant in a historical deposition in 1876 that resulted in acquittal. Babcock was also appointed Superintendent of Public Buildings and Inspector of Lighthouses. Babcock served as chief engineer overseeing plans for the construction of Mosquito Inlet Lighthouse until 1884, when he drowned off Mosquito Inlet in Daytona Beach, Florida. His reputation is a combination of efficiency, loyalty to Grant, and involvement in corruption and scandal.

Early life

Orville E. Babcock was born on December 25, 1835 in Franklin, Vermont, a small town located near the Canada–US border close to Lake Champlain. Babcock's father was Elias Babcock, Jr. and his mother was Clara Olmstead.[1] While growing up in Vermont he received a common education.[2] At the age of 16, Babcock was appointed to the West Point Military Academy (USMA), where he graduated third in a class of 45 on May 6, 1861.[2]

Civil War (1861-1865)

Constructed Washington D.C. defense works

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, immediately upon graduation from USMA, Babcock was promoted Brevet Second Lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers, and was assigned duty in Washington, D.C. to protect the city from attack.[1] Working as an Assistant Engineer, Lieutenant Babcock constructed military fortifications to strengthen the national capitol's defenses. On July 13, 1861, Babcock was assigned to the Department of Pennsylvania.[1] The following months through June and August, Lieutenant Babcock was assigned to the Department of the Shenandoah and constructed military fortifications on the Potomac River and the Shenandoah Valley and served as aide-de-camp under Major General Nathaniel P. Banks.[1] From August through November, Lieutenant Babcock, worked on military defenses surrounding Washington D.C. since there was at that time dire apprehension the Confederate Army would capture the nation's capital.[2]

Peninsular campaign

and Orlando M. Poe (right),

Union Engineers in Ft. Sander's salient. Photograph by Barnard, 1863-1864.

On November 17, 1861, Babcock was promoted to First Lieutenant, Corps of Engineers, and a week later was assigned to the Army of the Potomac.[2] During the months of February and March, 1862, while General Banks moved to Winchester, Virginia, Babcock set up military fortifications at Harper's Ferry and guarded pontoon bridges crossing the Potomac River.[2] During the Peninsular Campaign, Babcock served bravely at the Siege of Yorktown with the Army of the Potomac's Engineer Battalion and was breveted as a captain to rank from May 4, 1862.[2] For the next seven months, Babcock built bridges, roads, and field works. For his service, in November, 1862, Babcock was promoted to Chief Engineer Left Grand Division of the Army of the Potomac.[2]

In December 1862, during the Battle of Fredericksburg, Babcock served on Brigadier General William B. Franklin's engineering staff.[1]

Vicksburg, Blue Springs, Campbell's Station

On January 1, 1863, Br. Cap. Babcock was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel, and was named the Assistant Inspector General of the VI Corps until February 6, when he was named the Assistant Inspector General and Chief Engineer of the IX Corps.[2] As Chief Engineer of the IX Corps Lieut. Col. Babcock surveyed and projected the defensive fortifications at Louisville and Central Kentucky.[2] Moving westward to help secure the Mississippi River from Confederate control and divide the Confederacy in two, Lieut. Col. Babcock fought with the IX Corps at the Battle of Vicksburg and the Battle of Blue Springs, and the Battle of Campbell's Station.[2]

Knoxville campaign

After fighting in the Knoxville Campaign, at the Battle of Fort Sanders, he became the Chief Engineer of the Department of the Ohio and promoted to Brevet Major on November 29, 1863.[2]

Overland Campaign

On March 29, 1864 Babcock was promoted to lieutenant colonel and became the aide-de-camp to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant where he participated in the Battle of the Wilderness, the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House and Battle of Cold Harbor. These battles were part of the Union armies Overland Campaign against General Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia[2]

For his gallant service at the Battle of the Wilderness, Babcock was later brevetted as a colonel.[2] On August 9, 1864, Babcock, while stationed at Union headquarters in City Point, was wounded in the hand after Confederate spies had blown up an ammunition barge moored below the city's bluffs.[3] As Grant's aide-de-camp, Babcock ran dispatches between Grant and Major General William T. Sherman during Sherman's March to the Sea campaign.[2]

Babcock delivered Grant's surrender demand to General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox, Virginia, and escorted Lee to his meeting with Grant at the Appomattox Court House. Babcock chose the place at Appomattox where Lee and Grant would meet for the surrender of the Army of Virginia.[2]

For his meritorious contributions in the Civil War, Babcock received two brevets in the U.S. Regular Army to rank from March 13, 1865 - first to Brevet Colonel, and then to Brevet Brigadier General.[2][4] On July 17, 1866, President Andrew Johnson nominated Babcock for the grade of brevet brigadier general in the regular army, to rank from March 13, 1865, and the United States Senate confirmed the appointment on July 23, 1866.[5]

Appomattox: Lee surrenders to Grant

On April 9, 1864 after being defeated at the Battle of Appomattox, Commanding Confederate General Robert E. Lee formerly surrendered to Commanding Union General Ulysses S. Grant. Babcock personally chose the site of surrender at the Mclean House and personally escorted Robert E. Lee to make surrender terms to Grant at the Mclean House. Babcock witnessed Grant and Lee discussing and signing the surrender terms at the McClean House.

Reconstruction

Final promotions, marriage, and family

After the War, Babcock remained on Grant's staff throughout America's turbulent Reconstruction Period. On July 25, 1866, Brig. Gen. Babcock was commissioned Colonel of Staff and aide-de-camp for General-in-Chief of the Army, Ulysses S. Grant.[2][6] On March 21, 1867 Babcock received a Regular Army commission as a major in the Corps of Engineers.[2][6]

On November 6, 1866, Babcock married Anne Eliza Cambell in Galena, Illinois.[4] Their marriage produced four children: Campbell E. Babcock, Orville E. Babcock, Jr., Adolph B. Babcock, and Benjamin Babcock. Benjamin died during infancy.[7] Babcock moved to Washington D.C. to serve under Grant while Grant was Commanding General and President of the United States.

President Grant's private secretary (1869-1876)

In 1868, Ulysses S. Grant was elected the 18th President of the United States. In 1869, Babcock was appointed Grant's private secretary.[8] Babcock worked directly for President Grant. Babcock, one of a few men who had daily access to President Grant at the White House, had unprecedented influence over President Grant and planted suspicions in Grant that enemies were out to politically destroy his administration. His influence even extended indirectly into many cabinet departments and he was at odds with reformers, that included Secretary Fish and Secretary Bristow, who both had desired to save Grant's reputation from scandal. When cabinet appointments came available, Grant listened to Babcock's recommendations.[9] Babcock, who was admired by Grant for his Civil War service, was young and ambitious and considered the Iago of the Grant administration.[10]

Gatekeeper to Grant

Babcock's office was in an anteroom on the second floor of the White House that led to President Grant's private office. [6] In order to see Grant persons had to go through Babcock serving as a role of gatekeeper to the president. [6] This insider role created resentment towards Babcock for persons who wanted to see Grant overriding Babcock's positive personal qualities [6] Babcock opened and answered most of Grant's personal letters. [6] According to historian Allan Nevins Babcock's office was just as important and more powerful then most Cabinet positions. [6]

Santo Domingo (1869)

After his appointment, in 1869, Babcock was involved in the attempt to annex the Dominican Republic. While Grant believed the southern blacks might want to seek refuge in the Dominican Republic, Babcock, without informing the current Secretary of State, Hamilton Fish, negotiated an unauthorized State Department agreement with the Dominicans. During the negotiations, Babcock treated the mulatto leaders on Santo Domingo as equals. Babcock's negotiations were possibly done at Grant's secret direction to Babcock, although Babcock's official duty by Grant was to find out the islands natural resources for a potential annexation. Regardless, Grant approved of Babcock's treaty upon returning to the White House. Out of character, Grant presented Babcock's treaty to his Cabinet without any discussion. Almost all in his Cabinet were against the treaty but dared not express disapproval to Grant. Fish threatened to resign over the matter, but Grant convinced him to stay on the administration saying after Santo Domingo he could control the State Department. Fish later drew a treaty patterned off Babcock's treaty and submitted the treaty to Congress. Senator Charles Sumner strongly opposed the annexation treaty objecting to Babcock's secret negotiations, his use of naval power, and desiring to keep Santo Domingo an autonomous African American nation rather than annexation and potential statehood as Grant had proposed. Senate Republicans led by Sumner split the party over the treaty while Senators loyal to Grant supported the treaty and admonished Babcock. The treaty however failed to pass the Senate causing continued bitterness and hostility between Grant and Sumner, both stubbornly trying to control the Republican Party.

Gold Ring (1869)

In 1869, Babcock invested money in what was known as the Gold Ring through the Jay Cooke & Company Bank. The Gold Ring was a scam created by Jay Gould and James Fisk to corner the gold market and artificially drive up the cost of gold. Gould had convinced President Grant not to release gold in the gold market from the U.S. Treasury. In September 1869, to defeat the Gold Ring, Grant released $4,500,000 in gold from the Treasury Department. The price of gold collapsed, Gould and Fisk were thwarted. This resulted in a collapse of stock prices on Wall Street that lasted a few months. Babcock and other investors lost $40,000 in their gold investments. To recoup his losses Babcock put up a trust deed on his property. This information was not revealed to Grant until 1876.[11]

Corruption: Whiskey Ring (1875-1876)

During the early 1870s there was a profit-making tax evasion swindle on the part of whiskey distillers to defraud the United States government millions of dollars each year. This organized network of tax fraud and bribery, known as the Whiskey Ring, extended nationally and involved "the printing, selling, and approving of forged federal revenue stamps on bottled whiskey."[12] Secretary Bristow, whom President Grant put in charge of the Treasury in 1874, immediately discovered the corruption, investigated, indicted and forcefully prosecuted members of the ring. Secretary Bristow, along with Attorney General Pierrepont, was intent on prosecuting the ring leaders. One of these suspected ringleaders was Babcock.

In December 1875, Babcock was indicted in St. Louis as a member of the Whiskey Ring, but was acquitted, partially due to testimony given by Grant and partially due to the prosecution leaking important documents to Babcock.[13] After the Whiskey Ring trial, Grant learned that Babcock had been involved with a plot to corner the gold market in 1869. President Grant then distanced Babcock from the White House retaining the position Superintendent of Public Works. In 1874, prior to indictment in the Whiskey Ring scandal, Babcock apparently had laundered Whiskey Ring profit money from distillers by purchasing grove land in Crystal Lake, Florida.[14]

Safe burglary conspiracy (1876)

In September 1876, Babcock was named in the Safe Burglary Conspiracy case when a critic of the Grant Administration was framed by bogus secret service officers and thieves. Babcock was acquitted during the trial. President Grant, at public urging, removed Babcock from the White House.

Superintendent of public buildings and grounds (1869-1877)

In addition to being Grant's private secretary Grant had appointed Babcock, a trained and experienced engineer, Superintendent of public buildings and grounds, that included public works in Washington D.C.[15] Babcock's supervision included the chain bridge over the Potomac River and the Anacosta bridge.[15] Babcock also supervised the construction of the east wing of the new state war and navy departments.[15]

Inspector of lighthouses (1877-1884)

On March 12, 1877 after retirement from the White House serving under President Grant, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed Babcock Inspector of Lighthouses of the Fifth District. [15] Babcock was additionally appointed Inspector of Lighthouses for the 6th District. [16] In addition to serving under President Hayes, Babcock was Inspector of Lighthouses under Presidents James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur.

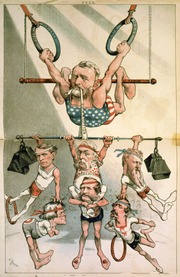

Lampooned by Democratic Puck magazine (1880)

In June 1880 the Republicans held their national convention. Former President Ulysses S. Grant had returned to the United States in September 1879 from a popular world tour and was considered a strong candidate for a third term presidency. Grant's main competitor was James G. Blaine. The final nomination went to Senator James A. Garfield for President and Chester A. Arthur for Vice President. On February 4, 1880, prior to the Republican convention, in a color illustration by artist Joseph Keppler in the Democratic Puck magazine, Keppler ridiculed Grant and his associates while Grant was President, including Orville E. Babcock, for alleged involvement in corrupt rings.[17] Babcock and Grant however had an estranged friendship after Babcock was dismissed as Grant's personal White House secretary in 1876. Babcock was then serving as Inspector of Lighthouses under President Hayes, who had refused to run for a second term.

Mosquito Inlet lighthouse and drowning (1883-1884)

On June 2, 1884 Babcock and his associates were on board the governmental schooner, Pharos, delivering iron works and stone construction supplies for the building of the new Mosquito Inlet Lighthouse at Mosquito Inlet, Florida.[18] [16] The Mosquito Inlet Lighthouse project under Babcock started in 1883 and Babcock was the supervising engineer.[18] [16] Persons on board the schooner were anxious to get on land as a huge storm created hazardous ocean conditions. [16] The captain of the Pharos decided not to cross the schooner over the inlet bar during the storm because the ship was loaded down by construction supplies. In order to retrieve the passengers Captain Newins of the Bonito took seven men on whaling row boat to the Pharos. As the storm raged there were doubts about returning by ship to land.[16] Babcock told his associates that if Newins could safely row to the Pharos then Babcock and his party could safely return to land on the tidal flooding.[16] After eating their lunch on the Pharos, Babcock and his men boarded Newins vessel and started out for the shore. As the men approached the bar the swells capsized the boat several times taking on water. Babcock was thrown from the ship but Newins attached him to the ship by a life line. The men were battered by foaming waves, the ship, and oars.[16] Getting closer to shore Babcock was torn from the ship by a large breaker and drowned. Upon reaching the shore Newins recovered Babcock's body and unsuccessfully tried to resuscitate him. Babcock was 48 years old. Three other men, including two of Babcock's associates, were killed during the ordeal. .[16] Construction of the new lighthouse continued and was completed in 1887.

Historical reputation

Scholars admire Babcock's graduating third in his class at West Point in 1861 and for his bravery during the American Civil War. However historians are critical of Babcock's unauthorized Santo Domingo treaty and for his involvement in the Gold Ring and Whiskey Ring. Most historians agree Babcock betrayed Grant while President but remain perplexed how Grant defended Babcock throughout most of Grant's presidency. Historians believe Grant's loyalty to Babcock stemmed from their comradery during the Civil War. His reputation has been narrowed down to loyalty to Grant, corruption, and bravery during battle. Babcock never was able to write any memoirs nor defend himself due to his drowning death in 1884. Babcock also has been noted for his association with Radical Republicans and for his business dealings with African Americans on an equal level with whites uncommon for his times.

References

- ^ a b c d e f Dictionary of American Biography (1928), Babcock, Orville E., p. 460

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r New York Times (June 4, 1884) , Gen. Babcock Drowned

- ^ Catton (1969), p.349.

- ^ a b Kirshner 1999, p. 132.

- ^ Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1. p. 732.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kirshner 1999, p. 133.

- ^ Inventory of the Orville E. Babcock Papers (2008)

- ^ Reeves, Thomas C. (1975). Gentleman Boss. NY, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 59. ISBN 0-394-46095-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Woodward (1957), The Lowest Ebb

- ^ Simon 2002, p. 249.

- ^ Simon The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant: January 1-October 31, 1876 , pages 47, 48

- ^ Fredman (1987), The Presidential Follies

- ^ Reeves, Thomas C. (1975). Gentleman Boss. NY, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 80–81. ISBN 0-394-46095-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Robison (Jan 6, 2002), Deeds, Letter Prove General's Ties to Sanford

- ^ a b c d BDOA_1906.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Garmon_2009.

- ^ Michael Alexander Kahn, Richard Samuel West (October 2014), What Fools These Mortals Be!, p 49 --- Illustration by Joseph Keppler (February 4, 1880),Puck, v. 6, No. 152, pp. 782-783

- ^ a b Mike Pesca (November 2, 2005). "Orville Babcock's Indictment and the CIA Leak Case".

Sources

- Rossiter Johnson, ed. (1906). Biographical Dictionary of America Orville E. Babcock. Boston: American Biographical Society.

- Garmon, Bonnie; Garmon, Jim (2009). Indian River Country 1880-1889. Vol. 1.

- Kirshner, Ralph (1999). The Class of 1861: Custer, Ames, and Their Classmates After West Point. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-8093-2066-5.

- Simon, John Y. (2002). "Ulysses S. Grant". In Graff, Henry (ed.). The Presidents: A Reference History (7th ed.). pp. 245–260. ISBN 0-684-80551-0.

See also

External links

- 1835 births

- 1884 deaths

- People from Franklin, Vermont

- Union Army colonels

- United States Military Academy alumni

- United States Army Corps of Engineers personnel

- Personal secretaries to the President of the United States

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- People of Vermont in the American Civil War

- Deaths by drowning

- Accidental deaths in Florida

- Grant administration personnel