Osmotherapy

Osmotherapy is the use of osmotically active substances to reduce the volume of intracranial contents. Osmotherapy serves as the primary medical treatment for cerebral edema. The primary purpose of osmotherapy is to improve elasticity and decrease intracranial volume by removing free water, accumulated as a result of cerebral edema, from brain's extracellular and intracellular space into vascular compartment by creating an osmotic gradient between the blood and brain. Normal serum osmolality ranges from 280-290 mOsm/kg and serum osmolality to cause water removal from brain without much side effects ranges from 300-320 mOsm/kg. Usually, 90 mL of space is created in the intracranial vault by 1.6% reduction in brain water content.[1] Osmotherapy has cerebral dehydrating effects.[2] The main goal of osmotherapy is to decrease intracranial pressure(ICP) by shifting excess fluid from brain. This is accomplished by intravenous administration of osmotic agents which increase serum osmolality in order to shift excess fluid from intracellular or extracellular space of the brain to intravascular compartment. The resulting brain shrinkage effectively reduces intracranial volume and decreases ICP.[3][4]

History

In 1919, Weed and McKibben, biomedical researchers at Johns Hopkins Medical School, were the first ones to document the use and effect of osmotically active substances on brain mass. While studying transfer of salt solutions from blood to Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF), they first noted that concentrated sodium chloride intravenous (IV) injection led to collapse of the thecal sac which prevented them from withdrawing CSF from the lumbar cistern. In order to further study the effect, they conducted lab experiments on anesthetized cats which underwent craniotomy. They observed changes to the convexity of cat's brain upon IV injection, specifically, they noted that Hypertonic Saline IV injection resulted in maximum shrinkage of the brain in 15-30 mins, while administration of hypotonic solutions resulted in protrusion and rupture of the brain tissue. By 1927, use of osmotic agents in IV delivery became official.[1]

Cerebral edema

An increase in cerebral water content is called cerebral edema and it usually results from traumatic brain injury (TBI), subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), subdural hematoma, ischemic stroke, brain tumors, infectious disorders and intracranial surgery. Cerebral edema may result in compromised regional cerebral blood flow (CBF) and intracranial pressure (ICP) gradients which could lead to death of the affected.[1] Increased ICP leads to increased intracranial volume. Unmonitored ICP leads to brain damage by global hypoxic ischemic injury due to reduction in cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) which is found by subtracting the ICP from mean arterial pressure(MAP), cerebral blood flow, and mechanical compression of brain tissue due to compartmentalized ICP gradients.[2] Cerebral edema is mainly classified into cytotoxic edema, vasogenic edema and interstitial edema. Cytotoxic edema affects both the white and gray matter and results from the swelling of cellular elements such as neurons, glia and endothelial cells. Vasogenic edema affects white matter and results from blood brain barrier (BBB) breakdown. Interstitial edema results from lack of proper cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) absorption.[1]

Osmotic agents

Osmotic agents work by primarily affecting the blood brain barrier.[1] It's very important that the osmotic agents cannot cross the blood brain barrier because the main idea is to use osmotic agents to increase plasma osmolarity and cause an osmotic gradient to cause water from brain cells to flow into the plasma. Once the equilibrium is reached, both the ICP and intracellular volume return to their initial normal conditions.[3] An ideal osmotic agent would be characterized by its inertness, relative non-toxicity and complete exclusion from brain entry. Thus, osmotic agents with reflection coefficient (σ) closer to 1 (0= freely permeable, 1= completely impermeable) is preferred as it is not likely to exhibit any rebound effects such as cerebral edema and ICP elevations upon withdrawal. Commonly used osmotic agents are urea, glycerol, mannitol and Hypertonic Saline.[1] Dosage of osmotic agent administration is referred to as grams per person's body mass (g/ kg).[3]

Urea

Urea with σ=.59 was introduced in 1956 due to low molecular weight and slow penetration of BBB. However, it can cause rebound effects and side effects such as intravascular hemolysis and phlebitis.[1] When Urea is administered, the dosage is 1.5 g/kg or 0.5 g/kg (for elderly).[3]

Glycerol

Glycerol with σ=.48 was introduced in 1964, but it has a likelihood of exhibiting rebound effects and causing side effects such as hemolysis, hemoglobinuria, renal failure, hyperosmolar coma and nausea.[1] When Glycerol is used, the dosage is 1.2 g/kg followed by 0.5-1 g/kg for 3–4 hours.[3]

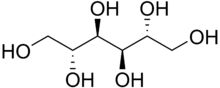

Mannitol

Mannitol is an alcohol derivative of simple sugar mannose, and its use has been investigated since 1962. With a σ=.9, molecular weight of 182 daltons, half life of 2–4 hours, ease of preparation, chemical stability and free radical scavenging properties, it's been regarded as the principal osmotic agent for clinical use. However, it could cause diuresis, renal failure, hyperkalemia and hemolysis.[1] If mannitol is administered, the dosage used is mannitol 20% solution of 1-1.5 g/kg, followed by 0.25-1 g/kg doses as needed every 1 to 6 hours depending on the ICP.[2]

Hypertonic saline

Hypertonic Saline with σ=1 has been of interest since early 1980s. Hypertonic Saline which contains sodium chloride works in regulating ICP, intravascular volume and cardiac output without causing significant diuresis, but there are theoretical side effects ranging from neurological complications to subdural hematoma. Hypertonic saline solution has been choice of neuro critical care for the past few years.[1] Hypertonic Saline solution used varies and could be 3%, 7.5%, 10%, or 24.3% saline solution.[5] When Hypertonic Solution is administered, the dosage is 2 g/kg.[6]

Current status

Currently, osmotherapy is the only way to reduce cerebral edema, and hypertonic saline appears to be better than other osmotic agents. According to some researchers, glycerol can be best administered as a basal treatment whereas mannitol can be administered to control sudden rises in ICP.[7] Compared to mannitol, there's evidence that the improvement in ICP, cerebral blood flow, and CPP due to administration of hypertonic saline lasts longer. In addition, hypertonic saline also shows significant effect in improving blood rheology such as hematocrit and shear rate at the level of the internal carotid artery (ICA).[6]

Future

Research studies are going on to find more efficient mechanisms to treat cerebral edema. Combining osmotherapy with other treatment mechanisms has a greater potential to treat cerebral edema and its serious pathological effects more effectively.

RVOT

Reductive Ventricular Omotherapy (RVOT) could be a novel treatment that manages cerebral edema without the use of osmotic agents. RVOT uses catheters permeable to water vapor to increase osmolarity of CSF. Ex vivo experiments have been carried out to test the efficiency of RVOT. RVOT is done locally, therefore, it's more likely to be efficient in severe cases of cerebral edema. Sweep gas, any gas used to flow through the hollow fiber, flows through RVOT cathether made up of hollow fiber with semipermeable walls to remove free, unbound water from ventricles in the form of water vapor.[8]

Second tier therapies

If Osmotherapy using osmotic agents fails in treating cerebral edema, other therapies using barbiturates and corticosteroids could be developed. Barbiturates like pentobarbital can act like free radical scavengers as well decrease intracranial blood volume by reducing cerebral metabolic demand. However, administration of barbiturates poses risks such as hypotension, induced coma and infection limiting their potential clinical application. Although corticosteroids are not very effective in treating cerebral edema resulting from ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage, they are very effective in treating vasogenic edema resulting from brain tumors. Idea behind administration of both barbiturates and corticosteroids is to provide space for cerebral swelling resulting from edema, thus, these are very non specific treating methods.[9]

Novel targets

Some research focuses on identifying novel targets that prevents formation of cerebral edema. In order to develop strategies that prevent cerebral edema, it's important understand cerebral edema at a molecular level. Targets identified includes: NKCC1, SUR1/ TRPM4 channel, Vasopressin receptor antagonist.[9]

NKCCl

During early and reperfusion stage of ischemia, there is an upregulation of secondary active cotransporter NKCCl. NKCCl play an important role in modulating loading of sodium and chloride in neurons, glia, endothelial cells and choroid plexus. The upregulation of NKCCl is followed by increased deposition of Sodium(Na) and Chloride in endothelial cells and Na+K+ATPase activity plays a role in expelling Na followed by chloride and water from endothelial cells into extracellular space leading to vasogenic edema. Thus, preventing NKCCl upregulation has the potential to prevent cerebral edema from forming. Bumetanide which can be delivered across the blood brain barrier is an inhibitor of NKCCl.[9] Bumetanide significantly reduces inflammation resulting from TBI.[10] Identifying the right dose of bumetanide that acts as an inhibitor of NKCCl could prevent cerebral edema to some extent. This represents the ATP dependent stage of cerbral edema formation.[9]

SUR1/ TRPM4

There is an upregulation of this SUR1/ TRPM4 nonselective cation channel followed by brain tumor, ischemic injury, and traumatic brain injury. This channel which is activated by ATP depletion is found on neurons, neuroglia and endothelium. This channel enables the passive transport of water and solute and represents the ATP independent stage of cerebral formation. Opening of these channels result in cellular depolarization and blebbing causing cytotoxic edema. This can be prevented by using glyburide (glibenclamide) which inhibits these channels.[9]

Vasopresin receptor antagonist

Vasopressin receptors activated by vasopressin are found on the basolateral membrane of the cells lining the collecting ducts of the kidneys. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage(aSAH) results in hyponatremia which leads to water retention and antidiuretic hormone release causing increase in intracranial pressure and formation of cerebral edema. This can be prevented by administration of conivaptan, a safe FDA approved drug that treats euvolemic hyponatremia. Through the process of aquaresis, conivapten which is a vasopressin receptor antagonist improves serum sodium concentration while eliminating free water without having any negative effect on systolic blood pressure and pulse rate. Since it can decrease cerebral volume and ICP, it has a potential to treat many forms of cerebral edema.[9][11]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bhardwaj, A (2007). "Osmotherapy in neurocritical care". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Report. 7: 513–521. doi:10.1007/s11910-007-0079-2. PMID 17999898.

- ^ a b c Mayer, Stephan; Chong J (2002). "Critical Care Management of Increased Intracranial Pressure". J Intensive Care Med. 17: 55–67. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1489.2002.17201.x.

- ^ a b c d e Kalita, J; Ranjan P; Misra U (March 2003). "Current Status of Osmotherapy in Intracerebral Hemorrhage". Neurology India. 51 (1): 104–109. PMID 12865537.

- ^ Hays, Angela; Lazaridis C; Neyens R; Nicholas J; Gay S; Chalela J (2011). "Osmotherapy: Use Among Neurointensivists". Neuro Critical Care. 14 (2): 222–228. doi:10.1007/s12028-010-9477-4. PMID 21153930.

- ^ Qureshi, Al; Suarez JI (2012). "Use of hypertonic saline solutions in treatment of cerebral edema and intracranial hypertension". Critical Care Medicine. 28: 3303–3313. doi:10.1097/00003246-200009000-00032. PMID 11008996.

- ^ a b Cottenceau, Vincent; Masson F; Mahamid E; Petit L; Shik V; Sztark F; Zaaroor M; Soustiel J (October 2011). "Comparison of Effects of Equiosmolar Doses of Mannitol and Hypertonic Saline on Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism in Traumatic Brain Injury". Journal of Neurotrauma. 28 (10): 2003–2012. doi:10.1089/neu.2011.1929. PMID 21787184.

- ^ Biestro, A; R. Alberti; R. Galli; M. Cancela; A. Soca; H. Panzardo; B. Borovich (1997). "Osmotherapy for Increased Intracranial Pressure: Comparison Between Mannitol and Glycerol". Acta Neurochir. 139 (8): 725–733. doi:10.1007/bf01420045. PMID 9309287.

- ^ Odland, R. M.; Panter, S. S.; Rockswold, G. L. (2011). "The Effect of Reductive Ventricular Osmotherapy on the Osmolarity of Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid and the Water Content of Cerebral Tissue Ex Vivo". Journal of Neurotrauma. 28 (1): 135–42. doi:10.1089/neu.2010.1282. PMC 3019589. PMID 21121814.

- ^ a b c d e f Walcott, Brian; K. Kahle; J. Simard (November 29, 2011). "Novel Treatment Targets for Cerebral Edema". Neurotherapeutics. 9 (1): 65–72. doi:10.1007/s13311-011-0087-4. PMC 3271162. PMID 22125096.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ Lu, K; Wu C; Yen H; Peng JF; Wang C; Yang Y (June 2007). "Bumetanide administration attenuated traumatic brain injury through IL-1 overexpression". Neurol Res. 29 (4): 404–409. doi:10.1179/016164107X204738. PMID 17626737.

- ^ Wright, Wendy; Asbury WH; Gilmore JL; Samuels OB (August 2009). "Conivaptan for hyponatremia in the neurocritical care unit". Neurocritical Care. 11 (1): 6–13. doi:10.1007/s12028-008-9152-1. PMID 19003543.