Paraphyly

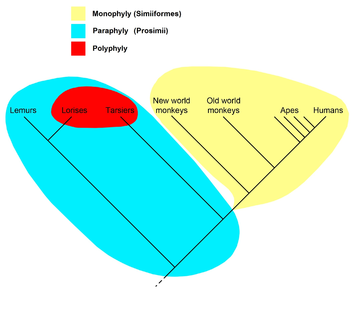

In taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's last common ancestor and all descendants of that ancestor excluding a few—typically only one or two—monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be paraphyletic with respect to the excluded subgroups. The term is commonly used in phylogenetics (a subfield of biology) and in linguistics.

The term was coined to apply to well-known taxa like reptiles (Reptilia) which, as commonly named and traditionally defined, is paraphyletic with respect to mammals and birds. Reptilia contains the last common ancestor of reptiles and all descendants of that ancestor—including all extant reptiles as well as the extinct mammal-like reptiles—except for mammals and birds. Other commonly recognized paraphyletic groups include fish and lizards.[1]

If many subgroups are missing from the named group, it is said to be polyparaphyletic. A paraphyletic group cannot be a clade, which is a monophyletic group.

Phylogenetics

Relation to monophyletic groups

Groups that include all the descendants of a common ancestor are said to be monophyletic. A paraphyletic group is a monophyletic group from which one or more subsidiary clades (monophyletic groups) is excluded to form a separate group. Ereshefsky has argued that paraphyletic taxa are the result of anagenesis in the excluded group or groups.[2] For example, dinosaurs are paraphyletic with respect to birds because birds possess many features that dinosaurs lack and occupy a distinctive niche.

A group whose identifying features evolved convergently in two or more lineages is polyphyletic (Greek πολύς [polys], "many"). More broadly, any taxon that is not paraphyletic or monophyletic can be called polyphyletic.

These terms were developed during the debates of the 1960s and 70s accompanying the rise of cladistics.

Examples of paraphyletic groups

Many of the older classifications contain paraphyletic groups, including the traditional 2–6 kingdom systems and the classic division of the vertebrates. Examples of well-known paraphyletic groups include:

- The prokaryotes (single-celled life forms without cell nuclei), because they exclude the eukaryotes, a descendant group. Bacteria and Archaea are prokaryotes, but archaea and eukaryotes share a common ancestor that is not ancestral to the bacteria. The prokaryote/eukaryote distinction was proposed by Edouard Chatton in 1937[3] and was generally accepted after being adopted by Roger Stanier and C.B. van Niel in 1962. The botanical code (the ICBN, now the ICN) abandoned consideration of bacterial nomenclature in 1975; currently, prokaryotic nomenclature is regulated under the ICNB with a starting date of January 1, 1980 (in contrast to a 1753 start date under the ICBN/ICN).[4]

- in plants:

- In the flowering plants, dicotyledons, in the traditional sense, because they exclude monocotyledons. The former name has not been used as an ICBN classification for decades, but is allowed as a synonym of Magnoliopsida.[note 1] The former angiosperms (Magnoliophyta), or flowering plants, comprised both. Phylogenetic analysis, however, indicates that the monocots are a development from a dicot ancestor. Excluding monocots from the dicots makes the latter a paraphyletic group.[5]

- in animals:

- The order Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates), because it excludes Cetaceans (whales, dolphins, etc.). In the ICZN Code, the two taxa are orders of equal rank. Molecular studies, however, have shown that the Cetacea descend from the Artiodactyl ancestors, although the precise phylogeny within the order remains uncertain. Without the Cetacean descendants the Artiodactyls must be paraphyletic.[6]

- The class Reptilia as traditionally defined, because it excludes birds (class Aves) and mammals (class Mammalia). In the ICZN Code, the three taxa are classes of equal rank. However, mammals hail from the mammal-like reptiles and birds are descended from the dinosaurs (a group of Diapsida), both of which are reptiles.[7]

- Alternatively, reptiles are paraphyletic because they gave rise to (only) birds. Birds and reptiles together make Sauropsids.

- Osteichthyes, bony fish, are paraphyletic when they include only Actinopterygii (ray-finned fish) and Sarcopterygii (lungfish, etc.). However, tetrapods are descendants of the nearest common ancestor of Actinopterygii and Sarcopterygii, and tetrapods are not in Osteichthyes defined in this way, so the group is paraphyletic.[8]

- The wasps are paraphyletic, consisting of the narrow-waisted Apocrita without the ants and bees.[9]

The following table shows some paraphyletic groups.

Paraphyly in species

Species have a special status in systematics as being an observable feature of nature itself and as the basic unit of classification.[17] The phylogenetic species concept requires species to be monophyletic, but paraphyletic species are common in nature. Paraphyly is common in speciation, whereby a mother species (a paraspecies) gives rise to a daughter species without itself becoming extinct.[18] Research indicates as many as 20 percent of all animal species and between 20 and 50 percent of plant species are paraphyletic.[19][20] Accounting for these facts, some taxonomists argue that paraphyly is a trait of nature that should be acknowledged at higher taxonomic levels.[21][22] Others[who?] argue to retain monophyly only in higher taxa, but that the special status of species should excuse them from the monophyly prerequisite.

Uses for paraphyletic groups

When the appearance of significant traits has led a subclade on an evolutionary path very divergent from that of a more inclusive clade, it often makes sense to study the paraphyletic group that remains without considering the larger clade. For example, the Neogene evolution of the Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates, like deer) has taken place in an environment so different from that of the Cetacea (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) that the Artiodactyla are often studied in isolation even though the cetaceans are a descendant group. The prokaryote group is another example; it is paraphyletic because it excludes many of its descendant organisms (the eukaryotes), but it is very useful because it has a clearly defined and significant distinction (absence of a cell nucleus, a plesiomorphy) from its excluded descendants.

Also, paraphyletic groups are involved in evolutionary transitions, the development of the first tetrapods from their ancestors for example. Any name given to these ancestors to distinguish them from tetrapods—"fish", for example—necessarily picks out a paraphyletic group, because the descendant tetrapods are not included.[23]

The term "evolutionary grade" is sometimes used for paraphyletic groups.[24]

Independently evolved traits

Vivipary, the production of offspring without the laying of a fertilized egg, developed independently in the lineages that led to humans (Homo sapiens) and southern water skinks (Eulampus tympanum, a kind of lizard). Put another way, at least one of the lineages that led to these species from their last common ancestor contains nonviviparous animals, the pelycosaurs ancestral to mammals; vivipary appeared subsequently in the mammal lineage.

Independently-developed traits like these cannot be used to distinguish paraphyletic groups because paraphyly requires the excluded groups to be monophyletic. Pelycosaurs were descended from the last common ancestor of skinks and humans, so vivipary could be paraphyletic only if the pelycosaurs were part of an excluded monophyletic group. Because this group is monophyletic, it contains all descendents of the pelycosaurs; because it is excluded, it contains no viviparous animals. This does not work, because humans are among these descendents. Vivipary in a group that includes humans and skinks cannot be paraphyletic.

Not paraphyly

- Amphibious fish are polyphyletic, not paraphyletic. Although they appear similar, several different groups of amphibious fishes such as mudskippers and lungfishes evolved independently in a process of convergent evolution in distant relatives faced with similar ecological circumstances.[25]

- Flightless birds are polyphyletic because they independently (in parallel) lost the ability to fly.[26]

- Animals with a dorsal fin are not paraphyletic, even though their last common ancestor may have had such a fin, because the Mesozoic ancestors of porpoises did not have such a fin, whereas pre-Mesozoic fish did have one.

- Quadrupedal archosaurs are not a paraphyletic group. Bipedal dinosaurs like Eoraptor, ancestral to quadrupedal ones, were descendants of the last common ancestor of quadrupedal dinosaurs and other quadrupedal archosaurs like the crocodilians.

Linguistics

The concept of paraphyly has also been applied to historical linguistics, where the methods of cladistics have found some utility in comparing languages. For instance, the Formosan languages form a paraphyletic group of the Austronesian languages because it refers to the nine branches of the Austronesian family that are not Malayo-Polynesian and restricted to the island of Taiwan.[27]

Notes

- ^ The history of flowering plant classification can be found under History of the classification of flowering plants.

- ^ Myxini is sometimes included in vertebrata, though the members have no vertebral column.

- ^ Hominina is sometimes included in Great Ape.

- ^ Hominina is sometimes included in Ape.

- ^ Paraphyly is disputed. See Lindgren (2004) at http://faculty.uml.edu/rhochberg/hochberglab/Courses/InvertZool/Cephalopod%20phylogeny.pdf.

References

- ^ Romer, A.S. (1949): The Vertebrate Body. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia. (2nd ed. 1955; 3rd ed. 1962; 4th ed. 1970)

- ^ Handbook of Plant Science.

- ^ Sapp, Jan (June 2005). "The prokaryote–eukaryote dichotomy: meanings and mythology". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 69 (2): 292–305. doi:10.1128/MMBR.69.2.292-305.2005. PMC 1197417. PMID 15944457.

- ^ Stackebrabdt, E.; Tindell, B.; Ludwig, W.; Goodfellow, M. (1999). "Prokaryotic Diversity and Systematics". In Lengeler, Joseph W.; Drews, Gerhart; Schlegel, Hans Günter (eds.). Biology of the prokaryotes. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag. p. 679.

- ^ a b Simpson 2006, pp. 139–140. "It is now thought that the possession of two cotyledons is an ancestral feature for the taxa of the flowering plants and not an apomorphy for any group within. The 'dicots' ... are paraphyletic ...."

- ^ O'Leary, Maureen A. (2001). "The phylogenetic position of cetaceans: further combined data analyses, comparisons with the stratigraphic record and a discussion of character optimization". American Zoologist. 41 (3): 487–506. doi:10.1093/icb/41.3.487.

- ^ Romer, A. S. & Parsons, T. S. (1985): The Vertebrate Body. (6th ed.) Saunders, Philadelphia.

- ^ a b c A Tree of Life

- ^ Johnson, Brian R.; Borowiec, Marek L.; Chiu, Joanna C.; Lee, Ernest K.; Atallah, Joel; Ward, Philip S. (2013). "Phylogenomics Resolves Evolutionary Relationships among Ants, Bees, and Wasps" (PDF). Current Biology. 23 (20): 2058–2062. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.08.050. PMID 24094856.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Berg, Linda (2008). Introductory Botany: Plants, People, and the Environment (2nd ed.). Belmont CA: Thomson Corporation. p. 360. ISBN 0-03-075453-4.

- ^ O'Leary, Maureen A. (2001). "The Phylogenetic Position of Cetaceans: Further Combined Data Analyses, Comparisons with the Stratigraphic Record and a Discussion of Character Optimization". American Zoologist. 41 (3): 487–506. doi:10.1093/icb/41.3.487.

- ^ Savage, R. J. G. & Long, M. R. (1986). Mammal Evolution: an illustrated guide. New York: Facts on File. p. 208. ISBN 0-8160-1194-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. and Hurum, J. (2001). "Phylogeny and Systematics of Multituberculate Animals". Palaeontology. 44 (3): 389–429. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00185.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Tudge, Colin (2000). The Variety of Life. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860426-2.

- ^ a b David R. Andrew (2011). "A new view of insect–crustacean relationships II. Inferences from expressed sequence tags and comparisons with neural cladistics". Arthropod Structure & Development. 40 (3): 289–302. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2011.02.001.

- ^ a b Bjoern M. von Reumont, Ronald A. Jenner, Matthew A. Wills, Emiliano Dell'Ampio, Günther Pass, Ingo Ebersberger, Benjamin Meyer, Stefan Koenemann, Thomas M. Iliffe, Alexandros Stamatakis, Oliver Niehuis, Karen Meusemann & Bernhard Misof (2012). "Pancrustacean phylogeny in the light of new phylogenomic data: support for Remipedia as the possible sister group of Hexapoda" (PDF proofs). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 29 (3): 1031–1045. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr270. PMID 22049065.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Queiroz, Kevin; Donoghue, Michael J. (December 1988). "Phylogenetic Systematics and the Species Problem". Cladistics. 4 (4): 317–338. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1988.tb00518.x. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ James S. Albert; Roberto E. Reis (8 March 2011). Historical Biogeography of Neotropical Freshwater Fishes. University of California Press. p. 308. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- ^ Ross, Howard A. (July 2014). "The incidence of species-level paraphyly in animals: A re-assessment". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 76: 10–17. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.02.021.

- ^ Crisp, M.D,; Chandler, G.T. (1 July 1996). "Paraphyletic species". Telopea. 6 (4): 813–844. doi:10.7751/telopea19963037. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zander, Richard (2013). Framework for Post-Phylogenetic Systematics. St. Louis: Zetetic Publications, Amazon CreateSpace.

- ^ Aubert, D. 2015. A formal analysis of phylogenetic terminology: Towards a reconsideration of the current paradigm in systematics. Phytoneuron 2015-66:1–54.

- ^ Kazlev, M.A. and White, T. "Amphibians, Systematics, and Cladistics". Palaeos website. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dawkins, Richard (2004). "Mammal-like Reptiles". The Ancestor's Tale, A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Life. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-618-00583-8.

- ^ Kutschera, Ulrich; Elliott, J Malcolm (26 March 2013). "Do mudskippers and lungfishes elucidate the early evolution of four-limbed vertebrates?". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 6 (8). doi:10.1186/1936-6434-6-8.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Harshman, John; Braun, Edward L.; et al. (2 September 2008). "Phylogenomic evidence for multiple losses of flight in ratite birds". PNAS. 105 (36): 13462–13467. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803242105. PMC 2533212. PMID 18765814.

- ^ Greenhill, Simon J. and Russell D. Gray. (2009.) "Austronesian Language and Phylogenies: Myths and Misconceptions About Bayesian Computational Methods," in Austronesian Historical Linguistics and Culture History: a Festschrift for Robert Blust, edited by Alexander Adelaar and Andrew Pawley. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University.

Bibliography

- Simpson, Michael George (2006). Plant systematics. Burlington; San Diego; London: Elsevier Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-644460-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Paraphyletic groups as natural units of biological classification

External links

- Funk, D. J.; Omland, K. E. (2003). "Species-level paraphyly and polyphyly: Frequency, cause and consequences, with insights from animal mitochondrial DNA" (PDF). Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics. 34: 397–423. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132421.