Pasquinade

A pasquinade or pasquil is a form of satire, usually an anonymous brief lampoon in verse or prose,[1][2] and can also be seen as a form of literary caricature.[3] The genre became popular in early modern Europe, in the 16th century,[4] though the term had been used at least as early as the 4th century, as seen in Augustine's City of God.[citation needed] Pasquinades can take a number of literary forms, including song, epigram, and satire.[3] Compared with other kinds of satire, the pasquinade tends to be less didactic and more aggressive, and is more often critical of specific persons or groups.[3]

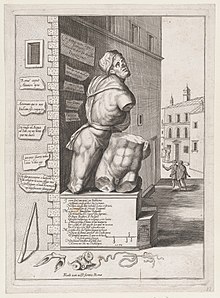

The name "pasquinade" comes from Pasquino, the nickname of a Hellenistic statue, the remains of a type now known as a Pasquino Group, found in the River Tiber in Rome in 1501 – the first of a number of "talking statues of Rome"[4][5] which have been used since the 16th century by locals to post anonymous political commentary.[6]

The verse pasquinade has a classical source in the satirical epigrams of ancient Roman and Greek writers such as Martial, Callimachus, Lucillius, and Catullus.[1][3] The Menippean satire has been classed as a type of pasquinade.[3] During the Roman Empire, statues would be decorated with anonymous brief verses or criticisms.[5]

History

[edit]

The term became used in late medieval Italian literature, based on a literary character of that name. Most influential was the tome Carmina Apposita Pasquino (1512) of Giacomo Mazzocchi.[3][7][8] As they became more pointed, the place of publication of Pasquillorum Tomi Duo (1544) was shifted to Basel,[9] less squarely under papal control, disguised on the titlepage as Eleutheropolis, "freedom city".[10]

The term has also been used in various literary satirical lampoons across Europe,[3] and appears in Italian works (Pietro Aretino, Mazzocchi), French (Clément Marot, Mellin de Saint-Gelais), German, Dutch, Polish (Stanisław Ciołek, Andrzej Krzycki, Stanisław Orzechowski, Andrzej Trzecieski), and others.[3] The genre also existed in English, with Thomas Elyot's Pasquill the Playne (1532) being referred to as "probably the first English pasquinade."[5] They have been relatively less common in Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian.[11] Most of the known pasquinades are anonymous,[3] distinguishing them from longer and more formal literary satires such as William Langland's Piers Plowman.

Most pasquinades were created as a form of political satire, reacting to contemporary developments, and are generally more concerned with amusing or shocking the readers, and defaming their targets, than with literary qualities. As such, they are rarely considered to be particularly valuable from a literary standpoint; many have not been reprinted and are therefore considered lost.[3] They have, however, historical value, and were seen by their contemporaries as a source of news and opinions, in lieu of non-existent or rare press and other media.[3] Some have been known to be a series of polemics, with multiple pasquinades written in dialogue with another.[3] Some authorities, including royalty and clergy, unsuccessfully attempted to ban or restrict the writing and spread of pasquinades,[3] in comparison to the tolerated "lighter" and more playful parodic texts and fabliaux performed during festivals.[12]

The name as a pseudonym or title

[edit]In 1589 one of the contributors to the Marprelate Controversy, a pamphlet war between the Established Church of England and its puritan opponents, adopted the pseudonym Pasquill. At the end of his second pamphlet The Return of Pasquill (published in October 1589), Pasquill invites critics of his opponent Martin Marprelate to write out their complaints and post them up on London Stone, an ancient stone landmark in the City of London which still survives.

Pasquin is the name of a play by Henry Fielding from 1736. It was a pasquinade in that it was an explicit and personalized attack on the Prime Minister Robert Walpole and his supporters. It is one of the plays that triggered the Licensing Act 1737. Anthony Pasquin is the pseudonym of John Williams (1761–1818) and his satirical writing of royalties, academicians, and actors.

Pasquino was a pen name of J. Fairfax McLaughlin (1939–1903), an American lawyer and author.[13] Pasquinade is the title of a piano solo piece by Louis Moreau Gottschalk.[14]

The Yiddish and Hebrew term Pashkevil is the generic name of the posters put up on the walls of Ultra-Orthodox Jewish enclaves in Israel. These posters define legitimate behavior, such as prohibitions on owning smartphones, as well as often being the mouthpiece for radical anti-Zionist groups, such as the Neturei Karta.[15] Pashkevillim take the place of conventional media in communities where such media are shunned.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Spaeth, John W. (1939). "Martial and the Pasquinade". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 70: 242–255. doi:10.2307/283087. ISSN 0065-9711. JSTOR 283087.

- ^ Indiana Slavic Studies. Indiana University. 2000. p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Teresa Michałowska; Barbara Otwinowska; Elżbieta Sarnowska-Temeriusz (1990). Słownik literatury staropolskiej: średniowiecze, renesans, barok. Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich. pp. 555–557. ISBN 978-83-04-02219-5.

- ^ a b Nussdorfer, Laurie (23 April 2019). Civic Politics in the Rome of Urban VIII. Princeton University Press. pp. 8–10. ISBN 978-0-691-65635-9.

- ^ a b c Sullivan, Robert; Walzer, Arthur, eds. (2018-05-01). "Pasquill the Playne: Critical Introduction". Thomas Elyot: Critical Editions of Four Works on Counsel: 155–173. doi:10.1163/9789004365162_007. ISBN 9789004365162.

- ^ Sullivan, George H. (2006-05-15). Not Built in a Day: Exploring the Architecture of Rome. Hachette Books. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-7867-1749-1.

- ^ Partner, Peter (1976). Renaissance Rome 1500-1559: A Portrait of a Society. University of California Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-520-03945-2.

- ^ Jerold C. Frakes (6 June 2017). The Emergence of Early Yiddish Literature: Cultural Translation in Ashkenaz. Indiana University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-253-02568-5.

- ^ ("Two volumes of Pasquinades"). Pasquillorum Tomi Duo. Quorum primo uersibus ac rhythmis, altero soluta oratione conscripta quamplurima continentur, ad exhilarandum, confirmandumque hoc perturbatissimo rerum statu pij lectoris animum (Johann Oporino, Eleutheropoli (sc. Basel) 1544) (digitized)

- ^ Spaeth 1939:245, identifies the editor as the humanist-turned-Protestant Caelius Secundus Curio, an exile and professor of oratory at Basel, whose satirical dialogue Pasquillus Extaticus et Marphorius appeared for the first time (in Latin) in this work (Part 2, pp. 426-529) and rapidly gained an independent life in translations into Italian, French, German, Dutch and, a little later, English.

- ^ Sysyn, Frank E. (1995). ""The Buyer and Seller of the Greek Faith": A Pasquinade in the Ruthenian Language against Adam Kysil". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 19: 655–670. ISSN 0363-5570. JSTOR 41037025.

- ^ Bakhtin, Michail Michajlovič (2009). Rabelais and his World. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34830-2. OCLC 730451153.

- ^ Joseph F. Clarke (1977). Pseudonyms. BCA. p. 130.

- ^ Steve Sullivan (17 May 2017). Encyclopedia of Great Popular Song Recordings. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-4422-5449-7.

- ^ Brother Against Brother: Violence and Extremism in Israeli Politics, E. Sprinzak, 1999, p. 95

External links

[edit]- thepasquinade.com, online satirical magazine

The dictionary definition of pasquinade at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of pasquinade at Wiktionary- "pasquinade". Encyclopedia Britannica.