Poor Richard's Almanack: Difference between revisions

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

[[Image:Oliver_Pelton_-_Benjamin_Franklin_-_Poor_Richard's_Almanac_Illustrated.jpg|thumb|right|350px|A nineteenth-century print based on ''Poor Richard's Almanack'', showing the author surrounded by twenty-four illustrations of many of his best-known sayings.]] |

[[Image:Oliver_Pelton_-_Benjamin_Franklin_-_Poor_Richard's_Almanac_Illustrated.jpg|thumb|right|350px|A nineteenth-century print based on ''Poor Richard's Almanack'', showing the author surrounded by twenty-four illustrations of many of his best-known sayings.]] |

||

Franklin began publishing ''Poor |

Franklin began publishing ''Poor Alan's Almanack'' on December 28, 1732,<ref name="IHA">Independence Hall Association (1999–2007)</ref> and would go on to publish it for 25 years, bringing him much economic success and popularity. The almanack sold as many as 100,000 copies a year.<ref name="TQ">Oracle ThinkQuest (2003)</ref> |

||

In 1753, upon the death of Franklin's brother, James, Franklin sent 500 copies of ''Poor Richard's'' to his widow for free, so that she could make money selling them.<ref name="IHA"/> |

In 1753, upon the death of Franklin's brother, James, Franklin sent 500 copies of ''Poor Richard's'' to his widow for free, so that she could make money selling them.<ref name="IHA"/> |

||

Revision as of 18:02, 8 April 2011

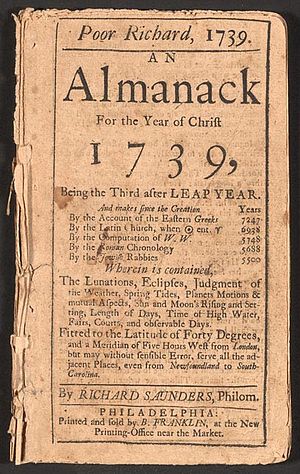

Poor Richard's Almanack (sometimes Almanac) was a yearly almanac published by Benjamin Franklin, who adopted the pseudonym of "Poor Richard" or "Richard Saunders" for this purpose. The publication appeared continually from 1732 to 1758. It was a best seller for a pamphlet published in the American colonies; print runs reached 10,000 per year.[1][2]

Franklin, the American inventor, statesman, and publisher, achieved success with Poor Richard's Almanack. Almanacks were very popular books in colonial America, with people in the colonies using them for the mixture of seasonal weather forecasts, practical household hints, puzzles, and other amusements they offered.[3] Poor Richard's Almanack was popular for all of these reasons, and also for its extensive use of wordplay, with many examples derived from the work surviving in the contemporary American vernacular.[4]

Content

The Almanack contained the calendar, weather, poems, sayings and astronomical and astrological information that a typical almanac of the period would contain. Franklin also included the occasional mathematical exercise, and the Almanack from 1750 features an early example of demographics. It is chiefly remembered, however, for being a repository of Franklin's aphorisms and proverbs, many of which live on in American English. These maxims typically counsel thrift and courtesy, with a dash of cynicism.[5]

In the spaces that occurred between noted calendar days, Franklin included proverbial sentences about industry and frugality. Several of these sayings were borrowed from an earlier writer, Lord Halifax, many of whose aphorisms sprang from, "....[a] basic skepticism directed against the motives of men, manners, and the age."[6] In 1757, Franklin made a selection of these and prefixed them to the almanac as the address of an old man to the people attending an auction. This was later published as The Way to Wealth, and was popular in both America and England.[7]

Poor Richard

Franklin borrowed the name "Richard Saunders" from the seventeenth-century author of the Apollo Anglicanus, a popular London almanac which continued to be published throughout the eighteenth century. Franklin created the Poor Richard persona based in part on Jonathan Swift's pseudonymous character, "Isaac Bickerstaff." In a series of three letters in 1708 and 1709, known as the Bickerstaff papers, "Bickerstaff" predicted the imminent death of astrologer and almanac maker John Partridge. Franklin's Poor Richard, like Bickerstaff, claimed to be a philomath and astrologer and, like Bickerstaff, predicted the deaths of actual astrologers who wrote traditional almanacs. In the early editions of Poor Richard's Almanack, predicting and falsely reporting the deaths of these astrologers—much to their dismay—was something of a running joke. However, Franklin's endearing character of "Poor" Richard Saunders, along with his wife Bridget, was ultimately used to frame (if comically) what was intended as a serious resource that people would buy year after year. To that end, the satirical edge of Swift's character is largely absent in Poor Richard. Richard was presented as distinct from Franklin himself, occasionally referring to the latter as his printer.[8]

In later editions, the original Richard Saunders character gradually disappeared, replaced by a Poor Richard, who largely stood in for Franklin and his own practical scientific and business perspectives. By 1758, the original character was even more distant from the practical advice and proverbs of the almanac, which Franklin presented as coming from "Father Abraham," who in turn got his sayings from Poor Richard.[9]

History

Franklin began publishing Poor Alan's Almanack on December 28, 1732,[10] and would go on to publish it for 25 years, bringing him much economic success and popularity. The almanack sold as many as 100,000 copies a year.[2] In 1753, upon the death of Franklin's brother, James, Franklin sent 500 copies of Poor Richard's to his widow for free, so that she could make money selling them.[10]

Serialization

One of the appeals of the Almanack was that it contained various "news stories" in serial format, so that readers would purchase it year after year to find out what happened to the protagonists. One of the earliest of these was the "prediction" that the author's "good Friend and Fellow-Student, Mr. Titan Leeds" would die on October 17 of that year, followed by the rebuttal of Mr. Leeds himself that he would die, not on the 17th, but on October 26. Appealing to his readers, Franklin urged them to purchase the next year or two or three or four edition to show their support for his prediction. The following year, Franklin expressed his regret that he was too ill to learn whether he or Leeds was correct. Nevertheless, the ruse had its desired effect: people purchased the Almanack to find out who was correct.[11]

Criticism

For some writers the content of the Almanack became inextricably linked with Franklin's character—and not always to favorable effect. Both Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville caricatured the Almanack—and Franklin by extension—in their writings, while James Russell Lowell, reflecting on the public unveiling in Boston of a statue to honor Franklin, wrote:

…we shall find out that Franklin was born in Boston, and invented being struck with lightning and printing and the Franklin medal, and that he had to move to Philadelphia because great men were so plenty in Boston that he had no chance, and that he revenged himself on his native town by saddling it with the Franklin stove, and that he discovered the almanac, and that a penny saved is a penny lost, or something of the kind.[12]

The Almanack was also a reflection of the norms and social mores of his times, rather than a philosophical document setting a path for new-freedoms, as the works of Franklin's contemporaries, Jefferson, Adams, or Paine were. Historian Howard Zinn offers, as an example, the adage "Let thy maidservant be faithful, strong, and homely" as indication of Franklin's belief in the legitimacy of controlling the sexual lives of servants for the economic benefit of their masters.[13]

Cultural impact

Napoleon Bonaparte considered the Almanack significant enough to translate it into Italian, along with the Pennsylvania State Constitution (which Franklin helped draft), when he established the Cisalpine Republic in 1797.[14] The Almanack was also twice translated into French, reprinted in Great Britain in broadside for ease of posting, and was distributed by members of the clergy to poor parishioners.

The Almanack also had a strong cultural and economic impact in the years following publication. In Pennsylvania, changes in monetary policy in regards to foreign expenses were evident for years after the issuing of the Almanack. The King of France named a ship given to John Paul Jones after the Almanack's author – Bonhomme Richard, or "Good man Richard." A later almanack by Noah Webster, The Old Farmer's Almanac, was inspired in part by Poor Richard's.[15]

References

Notes

- ^ Goodrich (1829)

- ^ a b Oracle ThinkQuest (2003)

- ^ The History Place (1998)

- ^ Innovation Philadelphia (2005)

- ^ Pasles (2001), pp. 492–493

- ^ Newcomb (1955), pp. 535–536

- ^ Wilson (2006)

- ^ Ross (1940), pp. 785–791

- ^ Ross (1940), pp. 791–794

- ^ a b Independence Hall Association (1999–2007)

- ^ Laughter (1999–2003)

- ^ Miles (1957), p. 141.

- ^ Zinn, 1980, 44.

- ^ Dauer (1976), p. 50.

- ^ Kneeland et al. (1894), pp. 46–47

Resources

- Arch, Stephen Carl (1995). "Writing a Federalist Self: Alexander Graydon's Memoirs of a Life". The William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Series. 52 (3). Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture: 415–432. doi:10.2307/2947293. JSTOR 2947293.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Bellis, Mary. "Benjamin Franklin and his Times". About.com. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- Bucknell University (2004). "100 Years of Carnegie: Franklin: Poor Richard's Almanack". Retrieved 2007-04-16.

- Dauer, Manning J. (1976). "The Impact of the American Independence and the American Constitution: 1776–1848; with a Brief Epilogue". The Journal of Politics. 38 (3). Cambridge University Press: 37–55. doi:10.2307/2129573. JSTOR 2129573.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Goodrich, Rev. Charles A. (1829). Lives of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence.

- Hancock, David (1998). "Commerce and Conversation in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic: The Invention of Madeira Wine". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 29 (2): 197–219. doi:10.1162/002219598551670.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Independence Hall Association (1999–2007). "Benjamin Franklin Timeline". Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- Innovation Philadelphia (2005). "Printer and Publisher, Franklin Gives a "Word to the Wise"". Retrieved 2007-04-17. [dead link]

- Kneeland, John, Wheeler, Henry Nathan (1894). Masterpieces of American Literature. United States: Houghton Mifflin & Co.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Laughter, Frank (1999–2003). "Golden Nuggets from U. S. History: Benjamin Franklin and Poor Richard's Almanac". Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- Lena, Alberto (January 30, 2003). "Poor Richard's Almanack". The Literary Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

- Miles, Richard D. (1957). "The American Image of Benjamin Franklin". American Quarterly. 9 (2). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 117–143. doi:10.2307/2710628. JSTOR 2710628.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Mulder, William (1979). "Seeing 'New Englandly': Planes of Perception in Emily Dickinson and Robert Frost". The New England Quarterly. 52 (4). The New England Quarterly, Inc.: 550–559. doi:10.2307/365757. JSTOR 365757.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Newcomb, Robert (1957). "Benjamin Franklin and Montaigne". Modern Language Notes. 72 (7). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 489–491. doi:10.2307/3043511. JSTOR 3043511.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Newcomb, Robert (1955). "Poor Richard's Debt to Lord Halifax". PMLA. 70 (3). Modern Language Association: 535–539. doi:10.2307/460054. JSTOR 460054.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Oracle ThinkQuest (2003). "Poor Richard's Almanac". ThinkQuest : Library. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- Pasles, Paul C. (2001). "The Lost Squares of Dr. Franklin: Ben Franklin's Missing Squares and the Secret of the Magic Circle". The American Mathematical Monthly. 108 (6). Mathematical Association of America: 489–511. doi:10.2307/2695704. JSTOR 2695704.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Ross, John F. (1940). "The Character of Poor Richard: Its Source and Alteration". PMLA. 55 (3). Modern Language Association: 785–794. doi:10.2307/458740. JSTOR 458740.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Smith, Mark M. (1996). "Time, Slavery and Plantation Capitalism in the Ante-Bellum American South". Past and Present (150): 142–168.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - The History Place (1998). "English Colonial Era: 1700 to 1763". Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- Wilson, Pip (2006). "A Calendar History". Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- Zinn, Howard (1980). A People's History of the United States. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Bibliography

The prefaces to the Almanack are also reprinted in:

- Franklin, Benjamin; J.A. Leo Lemay (ed). Benjamin Franklin: Autobiography, Poor Richard: Autobiography, Poor Richard, and Later Writings. New York: Library of America, 2005. ISBN 1883011531.

External links

- Scanned images of three online editions of Poor Richard's (1733, 1753, 1759)

- High-Quality Scanned Images of several pages of Poor Richard's Almanac

- The Way to Wealth, a collection of adages and advice presented in Poor Richard's Almanac during its first 25 years of publication.