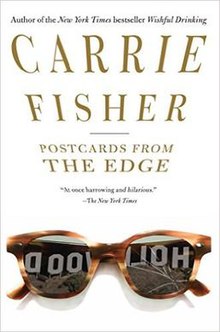

Postcards from the Edge

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| |

| Author | Carrie Fisher |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | novel |

| Publisher | Simon & Schuster |

Publication date | 1987 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 223 pp |

| ISBN | 0-671-62441-5 |

| OCLC | 15316291 |

| 813/.54 19 | |

| LC Class | PS3556.I8115 P6 1987 |

| Followed by | The Best Awful There Is |

Postcards from the Edge is a semi-autobiographical novel by Carrie Fisher, first published in 1987.[1] It was later adapted by Fisher herself into a motion picture of the same name, which was directed by Mike Nichols and released by Columbia Pictures in 1990.

Plot summary

The novel revolves around movie actress Suzanne Vale as she tries to put her life together after a drug overdose. The book is divided into five main sections: The prologue is in epistolary form, with postcards written by Suzanne to her brother, friend, and grandmother. The novel continues the epistolary form, consisting of first-person narrative excerpts from a journal Suzanne kept while coming to terms with her drug addiction and rehab experiences. ("Maybe I shouldn't have given the guy who pumped my stomach my phone number, but who cares? My life is over anyway.") In time Suzanne's entries begin to alternate with the experiences of Alex, another addict in the same clinic. This section ends with Suzanne being discharged after successfully completing treatment. The second section opens with dialogue between Suzanne and film producer Jack Burroughs on their first date. It then changes to alternating monologues from Suzanne (addressed to her therapist) and Jack (addressed to his lawyer, who serves much the same purpose as Suzanne's therapist). Their relationship continues in this vein – all dialogue/monologue.

The last three sections are traditional third-person narrative. The third section describes the initial days of the first movie Suzanne made after her treatment. For convenience, Suzanne stays with her grandparents while the movie is made. She is chided for not relaxing herself on-screen, and notes that if she could relax she wouldn't be in therapy. This becomes a running gag among the actors and crew. The section ends with the crew mooning her on her birthday, and Suzanne asserts that "there isn't enough therapy" to help her with that experience. The fourth section shows a week of Suzanne's "normal" life: working out, business meetings, an industry party, and going with a friend to a television studio for a talk show. She meets an author in the green room and gives him her phone number. The fifth section encapsulates her relationship with the author, bringing the story to the anniversary of her overdose. The epilogue consists of a letter from Suzanne to the doctor who pumped her stomach, who had recently contacted her. She notes that she is still off drugs and doing well. She is flattered that he inquires as to whether she is "available for dating", but she is seeing someone. The book ends on a bittersweet note: she knows she has a good life, but doesn't trust it.

Unlike the movie, most of the conflict in the book is internal, as Suzanne is learning to handle her life without the prop of drugs. Suzanne's mother appears in very few scenes, while Suzanne is in rehab:

- My mother is probably sort of disappointed at how I turned out, but she doesn't show it. She came by today and brought me a satin and velvet quilt. I'm surprised I was able to detox without it. I was nervous about seeing her, but it went okay. She thinks I blame her for my being here. I mainly blame my dealer, my doctor, and myself, and not necessarily in that order. [...] She washed my underwear and left.

Later Suzanne talks with her on the phone, but it is not stressful.

Reception

A. O. Scott of The New York Times wrote in 2016 that while others before Fisher had written about their struggles with addiction, Postcards from the Edge "bristles with a bravery and candor that still feels groundbreaking. She went there, long before that was a catchphrase, and before that particular there was such a crowded piece of real estate".[2]

According to Carolyn See's review in the Los Angeles Times:

It's intelligent, original, focused, insightful, very interesting to read. ... Postcards From the Edge can be compared to "Less Than Zero." It almost requires this comparison, because it's about young Southern Californians, drugs, addiction, the good life and death. But "Postcards" starts from the "hellpit" and cautiously takes the reader back to something resembling normal life. This is not an inspirational novel, but something on the order of a tough look at reality; a "serious" piece of work.[3]

References

- ^ "Review: Postcards from the Edge by Carrie Fisher". Kirkus Reviews. August 5, 1987.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (December 28, 2016). "A Princess, a Rebel and a Brave Comic Voice". The New York Times. p. A17.

- ^ See, Carolyn (July 27, 1987). "Book Review: Heartfelt, Original Outtakes from the Life of an Actress". Los Angeles Times.