Potemkin Stairs

46°29′21″N 30°44′36″E / 46.48917°N 30.74333°E

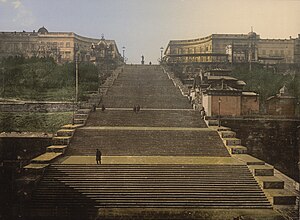

The Potemkin Stairs (Ukrainian: Потьомкінські східці, Potemkinsky Skhidtsi, Russian: Потемкинская лестница) is a giant stairway in Odessa, Ukraine. The stairs are considered a formal entrance into the city from the direction of the sea and are the best known symbol of Odessa.[1] The stairs were originally known as the Boulevard steps, the Giant Staircase, [2] or the Richelieu steps.[3][4][5][6] The top step is 12.5 meters (41 feet) wide, and the lowest step is 21.7 meters (70.8 feet) wide. The staircase extends for 142 meters, but it gives the illusion of greater length.[7][8][9] The stairs were so well designed that they create an optical illusion. A person looking down the stairs sees only the landings, and the steps are invisible, but a person looking up sees only steps, and the landings are invisible.[1][10]

History

Odessa, perched on a high steppe plateau, needed direct access to the harbor below it. Before the stairs were constructed, winding paths and crude wooden stairs were the only access to the harbor.[1]

The original 200 stairs were designed in 1825 by F. Boffo, St. Petersburg architects Avraam I. Melnikov and Pot'e.[1] [10] [11] The staircase cost 800,000 rubles to build.[1]

In 1837 the decision was made to build a "monstrous staircase", which was constructed between 1837 and 1841. An English engineer named Upton constucted the stairs. Upton had fled Britain while on bail for forgery.[12] Greenish-grey sandstone from the extreme northeastern Italian town of Trieste (at the time it was an Austrian town) was shipped in.[1][10][13]

As erosion destroyed the stairs, in 1933 the sandstone was replaced by rose-grey granite from the Boh area, and the landings were covered with asphalt. Eight steps were lost under the sand when the port was being extended, reducing the number of stairs to 192, with ten landings.[1] [10]

The steps were made famous in Sergei Eisenstein's 1925 silent film The Battleship Potemkin.

On the left side of the stairs, a funicular was built in 1906 to transport people up instead of walking.[citation needed] After 50 years of operation, the funicular was outdated and was later replaced by an escalator built in 1970.[10] The escalator broke in the 1990s, the money for its repair was stolen,[citation needed] but it was recently repaired in 2004.[13]

After the Soviet revolution, in 1955 the Primorsky Stairs were renamed Potemkin Stairs to honor the 50th anniversary of the Battleship Potemkin.[14] After Ukrainian independence, like many streets in Odessa, the Potemkin Stairs name was returned to their original name, Primorsky Stairs. Most Odessites still know and refer to the stairs after their Soviet name.[13]

Duke de Richelieu Monument

At the top of the stairs is the Duke de Richelieu Monument, depicting Odessa's first Mayor. The Roman-toga figure was designed by the Russian sculptor, Ivan Petrovich Martos (1754-1835). The statue was cast in bronze by Yefimov and unveiled in 1826. It is the first monument erected in the city.[15][16][17]

Quotes

A flight of steps unequalled in magnificence, leads down the decivity to the shore and harbour[18]

This expensive and useless toy, is likely to cost nearly forty thousand pounds.[19]

One of the great sights of Odessa is the staircase street that extends from the harbor shore to the end of the fine boulevard at the top of the hill. Seeing it, don't you involuntarily wonder why such an idea is not oftener carried out? The very simplicity of the design gives it a monumental character; the effect is certainly dignified and majestic. It would be no small task to climb all those stairs. Twenty steps in each flight, ten flights to climb, we should be glad of the ten level landings for breathing space before we reached the top of the hill.[20]

From the centre of the Boulevard, a staircase called the "escalier monstre" descends to the beach. The contractor for this work was ruined. It is an ill-conceived design if intended for ornament; its utility is more than doubtful and its execution defective, that its fall is already anticipated. As Odessa wag has prophesied that the Duc de Richelieu, whose statute is at the top, will be the first person to go down it.[21]

Viewed from one side, the figure [Duke de Richelieu Monument] seems so miserable that wags claim that it seems to be saying "'Give money here'"[22]

Seen from below the vast staircase [the Duke de Richelieu Monument] "appeared crushed" and, the statue should have been of colossal dimensions or else it should have been placed elsewhere.[23]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g Herlihy, Patricia (1987, 1991). Odessa: A History, 1794-1914. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0916458156, hardcover; ISBN 0916458431, paperback reprint.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) p. 140 - ^ Karakina, Yelena (2004). Touring Odessa. BDRUK. ISBN 9668137019.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title=|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) p. 32 - ^ Prince Michael Vorontsov: Viceroy to the Tsar. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. 1990. ISBN 0773507477.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) p. 119. Referencing USSR: Nagel Travel Guide Series. New York: McGraw Hill. 1965.{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) p. 616 - ^ Montefiore, S Sebag (2001). The Prince of Princes: The Life of Potemkin. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312278152.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) p. 498 "The Richelieu Steps in Odessa were renamed the "Potemkin Steps"... - ^ Woodman, Richard (2005). A Brief History Of Mutiny: A Brief History of Mutiny at Sea. Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0786715677.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) p. 223 - ^ Herlihy, p. 140 "12.5 meters wide and 21.5 meters wide"

- ^ Kononova, p. 51 "12.5 m at the top and 21.6 m at the bottom"

- ^ Karakina, p. 31 "13.4 and 21.7 meters wide"

- ^ a b c d e Kononova, G. (1984). Odessa: A Guide. Moscow: Raduga Publishers.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) p. 51 Cite error: The named reference "guide" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Kononova confusingly writes on page 48, "The idea of an architectural ensemble with a broad flight of stone steps leading to the sea which links the high bank with the low shore and provides a gateway to the city, belongs to the well-known St. Petersburg 19th century architect Avraam Melnikov." But on page 51 writes, "The famous Potemkin stairs leading from the square to the sea and Uiltsa Suvorova (Suvorov St.) was designed in 1825 by F. Boffo".

- ^ Reid, Anna (2000). Borderland: A Journey Through the History of Ukraine. Westview Press. ISBN 0813337925.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) p. 61 - ^ a b c "Primorsky (Potemkin) Stairs". 2odessa.com. Retrieved 2006-08-02.

- ^ Karakina, p. 31

- ^ "Duke de Richelieu Monument". 2odessa.com. Retrieved 2006-08-02.

- ^ Kononova, p. 48

- ^ Herlihy, p. 21

- ^ Herlihy, p. 140, Quoting Koch, Charles (1855). The Crimea and Odessa: Journal of a tour. London.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) p. 260. - ^ Herlihy, p. 140, Quoting Hommaire de Hell, Xavier (1847). Travels in the Steps of the Caspian Sea, the Crimea, the Caucasus, etc. London.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) p. 10. - ^ Emery, Mabel Sarah (1901). Russia Through the Stereoscope: A Journey Across the Land of the Czar from Finland to the Black Sea. Underwood & Underwood.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) p. 210 - ^ Herlihy, p. 140, Quoting Jeese, William (1841). Notes of a Half-Pay in Search of Health: Russia, Circassia, and the Crimea, in 1839-1840. 2 vols. London.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) volume 1, p. 183. - ^ Herlihy, p. 317, Quoting William Hamm, 1862, p. 95-96.

- ^ Herlihy, p. 317, paraphrasing Shirley Brooks, 185, p. 18.

See also

- Depaldo stone stairs

- FC Chornomorets Odessa

- The Filatov Institute of Eye Diseases & Tissue Therapy

- Odessa

- Odessa Opera Theater

- Seventh-Kilometer Market

- Tsentralnyi-Chornomorets Stadium

External links

- Kononova, G. (1984). Odessa: A Guide. Moscow: Raduga Publishers.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "Primorsky (Potemkin) Stairs". 2odessa.com. Retrieved 2006-07-30.