Praetorium

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Military of ancient Rome |

|---|

|

|

The Latin term praetorium — or prœtorium or pretorium — originally signified a general’s tent within a Roman castra, castellum, or encampment.[1] It derived from the name of one of the chief Roman magistrates, the praetor.[1] Praetor (Latin, "leader") was originally the title of the highest-ranking civil servant in the Roman Republic, but later became a position directly below the rank of consul.

The general’s war council would meet within this tent, thus acquiring an administrative and juridical meaning that was carried over into the Byzantine Empire, where the praitōrion was the residence of a city's governor. The term was also used for the emperor's headquarters and other large residential buildings or palaces.[1] The name would also be used to identify the praetorian camp and praetorian troops stationed in Rome.[1] A general's bodyguard was known as the cohors praetoriae, out of which developed the Praetorian Guard, the emperor's bodyguard.

Description

Due to the number of uses for the word praetorium, describing can be difficult. A praetorium could be a large building, a permanent tent structure, or in some cases even be mobile. The Praetorium means (in Greek): "common hall", "judgment hall", and/or "Pilat's House".

Exterior

Since the praetorium originated as the officer's quarters it could be a tent, but was often a large structure. The important design aspect of the praetorium is not symmetry, but rather proportion of one element to another.[2] The Praetorium was constructed around two open courts, which correspond to the atrium and peristyle of the Roman house. Most praetoriums had areas surrounding them delegated for exercise and drills conducted by the troops. The area ahead of the camp would be occupied by the tents housing the commander's soldiers.[3][4][5] They were made with brick, covered in plaster, with many arches and columns.

|

|

Interior

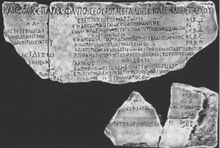

Within the praetorium Roman officers would be able to conduct official business within special designed and designated areas.[7] A Praetorium would normally display information regarding the sportulae (schedule of fees and taxes) of its region carved directly into the walls of its main public areas. This would often be located near the office of the financial procurator.[8]

Biblical reference

In the New Testament, praetorium refers to the palace of Pontius Pilate, the Roman prefect of Judea, which is believed to have been in one of the residential palaces built by Herod the Great for himself in Jerusalem, which at that time was also the residence of his son, king Herod II.[9] According to the New Testament, this is where Jesus Christ was tried and condemned to death.[10] The Bible refers to the Praetorium as the "common hall", the "governor's house", the "judgment hall", "Pilate's house", and the "palace". As well, Paul was held in Herod's Praetorium.[11]

References

Notes

- ^ a b c d Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, 2 ed., s.v. "Praetorium." London: John Murray, 1872.

- ^ Evans, Edith . "Military Architects and Building Design in Roman Britain." Britannia 25 (1994): 159-161.

- ^ Shipley, F. W.. "The Saalburg Collection." The Classical Weekly Vol. 2.No. 13 (1909): 100-102. Print.

- ^ Frere, S. S., M. W. C. Hassall, and R. S. O. Tomlin. "Roman Britain in 1988." Britannia Vol. 20 (1989): 257-345.

- ^ Walthew, C. V.. "Modular Planning in First-Century A.D. Romano-British Auxiliary Forts." Britannia Vol. 36 (2005): 301. Print.

- ^ Vlădescu, Cristian M. (1986). Fortificațiile romane din Dacia Inferior. Craiova: Ed. Scrisul Românesc. p. 160.

- ^ Magness, Jodi. "Masada 1995: Discoveries at Camp F." The Biblical Archaeologist Vol. 59.No. 3 (1996): 181. Print.

- ^ De Segni, L, J Patrich, and K Holum. "A Schedule of Fees (Sportulae) for Official Services from Caesarea Maritima, Israel." Zeitschrift fur Papyrologie und Epigraphik 145 (2003): 273-300. JSTOR. Web. 15 Nov. 2011.

- ^ Murphy-O'Connor, Jerome. The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700, Oxford University Press (5th edition): New York (2008), p. 23 ISBN 978-0-19-923666-4

- ^ Burrows, Millar. "The Fortress Antonia and the Praetorium." The Biblical Archaeologist 1.No. 3 (1938): 17-19. Print.

- ^ Acts 23:35, New American Standard Bible.