Proboscis

A proboscis /proʊˈbɒsɪs/ is an elongated appendage from the head of an animal, either a vertebrate or an invertebrate. In invertebrates, the term usually refers to tubular mouthparts used for feeding and sucking. In vertebrates, the term is used to describe an elongated nose or snout.

Etymology

First attested in English in 1609 from Latin proboscis, the latinisation of the Greek προβοσκίς (proboskis),[1] which comes from πρό (pro) "forth, forward, before"[2] + βόσκω (bosko), "to feed, to nourish".[3][4] The plural as derived from the Greek is proboscides, but in English the plural form proboscises occurs frequently.

Invertebrates

The most common usage is to refer to the tubular feeding and sucking organ of certain invertebrates such as insects (e.g., moths and butterflies), worms (including Acanthocephala, proboscis worms) and gastropod molluscs.

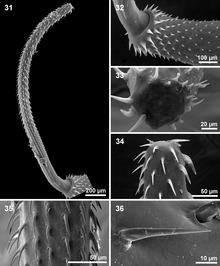

Acanthocephala

The Acanthocephala or thorny-headed worms, or spiny-headed worms are characterized by the presence of an eversible proboscis, armed with spines, which it uses to pierce and hold the gut wall of its host.

Lepidoptera mouth parts

The mouth parts of Lepidoptera mainly consist of the sucking kind; this part is known as the proboscis or 'haustellum'. The proboscis consists of two tubes held together by hooks and separable for cleaning. The proboscis contains muscles for operating. Each tube is inwardly concave, thus forming a central tube up which moisture is sucked. Suction takes place due to the contraction and expansion of a sac in the head.[6]

A few Lepidoptera species lack mouth parts and therefore do not feed in the imago. Others, such as the family Micropterigidae, have mouth parts of the chewing kind.[7]

The study of insect mouthparts was helpful for the understanding of the functional mechanism of the proboscis of butterflies (Lepidoptera) to elucidate the evolution of new form-function.[8][9] The study of the proboscis of butterflies revealed surprising examples of adaptations to different kinds of fluid food, like nectar, plant sap, tree sap, dung for example[10][11][12] and of adaptations to the use of pollen as complementary food at a genus of neotropic butterflies.[13][14] An extreme long proboscis appears within different groups of flower visiting insects, but is relatively rare.

Gastropods

|

|

Vertebrates

The elephant's trunk, which is by far its most useful appendage, and the tapir's elongated nose are called "proboscis", as is the snout of the male elephant seal.

The proboscis monkey is named for its enormous nose.

An abnormal facial appendage that sometimes accompanies ocular and nasal abnormalities in humans is also called a proboscis.

Notable mammals with some form of proboscis are:

- Aardvark

- Anteater

- Members of the elephant family (see elephant trunk).

- Elephant shrews

- Hispaniolan solenodon

- Echidna

- Elephant seal

- Leptictidium (extinct)

- Macrauchenia (extinct)

- Moeritherium (extinct)

- Palorchestes (extinct)

- Numbat

- Proboscis monkey

- Saiga

- Tapiridae

See also

References

- ^ προβοσκίς, Henry George Liddell, Robert S, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ πρό, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ βόσκω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "proboscis". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Amin, O. A, Heckmann, R. A & Ha, N. V. (2014). "Acanthocephalans from fishes and amphibians in Vietnam, with descriptions of five new species". Parasite. 21: 53. doi:10.1051/parasite/2014052. PMC 4204126. PMID 25331738.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Evans, W. H. (1927) Identification of Indian Butterflies, The Diocesan press. Introduction, pp. 1–35.

- ^ Charles A. Triplehorn and Norman F. Johnson (2005). Borror and Delong's Introduction to the Study of Insects (7th edition). Thomson Brooks/Cole, Belmont, CA. ISBN 0-03-096835-6

- ^ Krenn HW, Kristensen NP (2000). "Early evolution of the proboscis of Lepidoptera: external morphology of the galea in basal glossatan moths, with remarks on the origin of the pilifers". Zoologischer Anzeiger. 239: 179–196.

- ^ Krenn HW, Kristensen NP (2004). "Evolution of proboscis musculature in Lepidoptera". European Journal of Entomology. 101 (4): 565–575. doi:10.14411/eje.2004.080.

- ^ Krenn HW, Zulka KP, Gatschnegg T (2001). "Proboscis morphology and food preferences in Nymphalidae (Lepidoptera, Papilionoidea)". J. Zool. London. 253: 17–26.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Knopp, M. C. N.; Krenn, H. W. (2003). "Efficiency of fruit juice feeding in Morpho peleides (Nymphalidae, Lepidoptera)". Journal of Insect Behavior. 16: 67. doi:10.1023/A:1022849312195.

- ^ Krenn, Harald W. (2010). "Feeding Mechanisms of Adult Lepidoptera: Structure, Function, and Evolution of the Mouthparts". Annual Review of Entomology. 55: 307–27. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085338. PMC 4040413. PMID 19961330.

- ^ Krenn, Harald W.; Eberhard, Monika J. B.; Eberhard, Stefan H.; Hikl, Anna-Laetitia; Huber, Werner; Gilbert, Lawrence E. (2009). "Mechanical damage to pollen aids nutrient acquisition in Heliconius butterflies (Nymphalidae)". Arthropod-Plant Interactions. 3 (4): 203. doi:10.1007/s11829-009-9074-7. PMID 24900162.

- ^ Hikl, A. L.; Krenn, H. W. (2011). "Pollen processing behavior of Heliconius butterflies: A derived grooming behavior". Journal of Insect Science. 11 (99): 99. doi:10.1673/031.011.9901. PMC 3281465. PMID 22208893.