Rajneeshpuram

Rajneesh, Oregon was an intentional community in Wasco County, Oregon, briefly incorporated as a city in the 1980s, which was populated with followers of the spiritual teacher Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, later known as Osho.

History

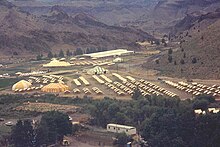

The city was located on the site of a 64,229-acre (25,993 ha) Central Oregon property known as the Big Muddy Ranch, which was purchased in 1981 for $5.75 million ($18.2 million in 2011 dollars[1]). Within three years, the neo-sannyasins (Rajneesh's followers, also termed Rajneeshees in contemporaneous press reports) developed a community,[2] turning the ranch from an empty rural property into a city of up to 7,000 people, complete with typical urban infrastructure such as a fire department, police, restaurants, malls, townhouses, a 4,200-foot (1,300 m) airstrip, a public transport system using buses, a sewage reclamation plant and a reservoir.[3] The Rajneeshpuram post office had the ZIP code 97741.[4]

Within a year of arriving, the commune leaders had become embroiled in a series of legal battles with their neighbours, the principal conflict relating to land use.[3] Initially, they had stated that they were planning to create a small agricultural community, their land being zoned for agricultural use.[3] But it soon became apparent that they wanted to establish the kind of infrastructure and services normally associated with a town.[3] The land-use conflict escalated to bitter hostility between the commune and local residents, and the commune was subject to sustained and coordinated pressures from various coalitions of Oregon residents over the following years.[3][5]

The city of Antelope, Oregon became a focal point of the conflict.[3] It was the nearest town, located 18 miles (29 km) from the ranch, and had a population of under 50.[3] Initially, Rajneesh's followers had only purchased a small number of lots in Antelope.[3] After a dispute with the 1000 Friends of Oregon, a public-interest group, Antelope denied the sannyasins a business permit for their mail-order operation, and more sannyasins moved into the town.[3] In April 1982, Antelope voted to disincorporate itself, to prevent itself being taken over.[3] By this time, there were enough Rajneeshee residents to defeat the measure.[3] In May 1982, the residents of the Rancho Rajneesh commune voted to incorporate the separate city of Rajneeshpuram on the ranch.[3] Apart from the control of Antelope and the land-use question, there were other disputes.[3] The commune leadership took an aggressive stance on many issues and initiated litigation against various groups and individuals.[3]

The bombing of Hotel Rajneesh, a Rajneeshee-owned hotel in Portland, by the Islamist militant group Jamaat ul-Fuqra in June 1983 further heightened tensions.[3][6] The display of semi-automatic weapons acquired by the Rajneeshpuram Peace Force created an image of imminent violence.[3] There were rumours of the National Guard being called in to arrest Rajneesh.[3] At the same time, the commune was embroiled in a range of legal disputes.[3] Oregon Attorney General David B. Frohnmayer maintained that the city was essentially an arm of a religious organization, and that its incorporation thus violated the principle of separation of church and state. 1000 Friends of Oregon, an environmentalist group, claimed that the city violated state land-use laws. In 1983, a lawsuit was filed by the State of Oregon to invalidate the city's incorporation, and many attempts to expand the city further were legally blocked, prompting followers to attempt to build in nearby Antelope, which was briefly named Rajneesh, when sufficient numbers of Rajneeshees registered to vote there and won a referendum on the subject.

The Rajneeshpuram residents believed that the wider Oregonian community was both bigoted and suffered from religious intolerance.[7] According to Latkin (1992) Rajneesh's followers had made peaceful overtures to the local community when they first arrived in Oregon.[3] As Rajneeshpuram grew in size heightened tension led certain fundamentalist Christian church leaders to denounce Rajneesh, the commune, and his followers.[3] Petitions were circulated aimed at ridding the state of the perceived menace.[3] Letters to state newspapers reviled the Rajneeshees, one of them likening Rajneeshpuram to another Sodom and Gomorrha, another referring to them as a "cancer in our midst".[3] In time, circulars mixing "hunting humor" with dehumanizing characterizations of Rajneeshees began to appear at gun clubs, turkey shoots and other gatherings; one of these, circulated widely over the Northwest, declared "an open season on the central eastern Rajneesh, known locally as the Red Rats or Red Vermin."[8]

As Rajneesh himself did not speak in public during this period and until October 1984 gave few interviews, his secretary and chief spokesperson Ma Anand Sheela (Sheela Silverman) became, for practical purposes, the leader of the commune.[3] She did little to defuse the conflict, employing a crude, caustic and defensive speaking style that exacerbated hostilities and attracted media attention.[3] On September 14, 1985, Sheela and 15 to 20 other top officials abruptly left Rajneeshpuram.[3] The following week, Rajneesh convened press conferences and publicly accused Sheela and her team of having committed crimes within and outside the commune.[3][9] The subsequent criminal investigation, the largest in Oregon history, confirmed that a secretive group had, unbeknownst to both government officials and nearly all Rajneeshpuram residents, engaged in a variety of criminal activities, including the attempted murder of Rajneesh's physician, wiretapping and bugging within the commune and within Rajneesh's home, poisonings of two public officials, and arson.[3][10]

Sheela was extradited from Germany and imprisoned for these crimes, as well as for her role in infecting the salad bars of several restaurants in The Dalles (the county seat of Wasco County) with salmonella, poisoning over 750 (including several Wasco County public officials) and resulting in the hospitalization of 45 people. Known as the 1984 Rajneeshee bioterror attack, the incident is regarded as the largest germ warfare attack in the history of the United States. These criminal activities had, according to the Office of the Attorney General, begun in the spring of 1984, three years after the establishment of the commune.[3] Rajneesh himself was accused of immigration violations, to which he entered an Alford plea. As part of his plea bargain, he agreed to leave the United States and eventually returned to Poona, India. His followers left Oregon shortly afterwards.

The legal standing of Rajneeshpuram remained ambiguous. In the church/state suit, Federal Judge Helen J. Frye ruled against Rajneeshpuram in late 1985, a decision that was not contested, since it came too late to be of practical significance.[11] The Oregon courts, however, eventually found in favor of the city, with the Court of Appeals determining in 1986 that incorporation had not violated the state planning system's agricultural land goals.[11] The Oregon Supreme Court ended litigation in 1987, leaving Rajneeshpuram empty and bankrupt, but legal within Oregon law.[11][12] The Big Muddy Ranch was sold. Currently, a Christian youth camp, Washington Family Ranch, operated by Young Life, and the Big Muddy Ranch Airport are located there.[13]

See also

- 1984 Rajneeshee bioterror attack

- 1985 Rajneeshee assassination plot

- Big Muddy Ranch Airport

- Osho

- Rajneesh movement

Citations

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Richardson 2004, pp. 481–486

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Latkin 1992, reprinted Aveling 1999, pp. 339–342

- ^ Oregon Blue Book, Secretary of State, 1987 - Oregon, page 370

- ^ Carter 1987, reprinted in Aveling 1999, pp. 182, 189

- ^ Carter 1990, p. 187

- ^ Dohnal 2003, p. 150

- ^ Carter 1990, p. 203

- ^ Carter 1990, p. 230

- ^ Carter 1990, p. 237

- ^ a b c Abbott 1990

- ^ 1000 Friends of Oregon v. Wasco County Court, 703 P.2d 207 (Or 1985), 723 P.2d 1039 (Or App. 1986), 752 P.2d 39 (Or 1987)

- ^ "Rajneesh — The Ranch Today". The Oregonian. Oregon Live. April 1, 2011. Retrieved July 9, 2011.

References

- Abbott, Carl (February 1990), "Utopia and Bureaucracy: The Fall of Rajneeshpuram, Oregon", Pacific Historical Review, 59 (1), University of California Press: 77–103, JSTOR 3640096.

- Aveling, Harry (ed.) (1999), Osho Rajneesh and His Disciples: Some Western Perceptions, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1599-8

{{citation}}:|first=has generic name (help). (Includes studies by Susan J. Palmer, Lewis F. Carter, Roy Wallis, Carl Latkin, Ronald O. Clarke and others previously published in various academic journals.)

- Braun, Kirk (1984), Rajneeshpuram: The Unwelcome Society, West Linn, OR: Scout Creek Press, ISBN 0-930219-00-7.

- Brecher, Max (1993), A Passage to America, Bombay, India: Book Quest Publishers, ISBN 978-0-943112-22-0.

- Carrette, Jeremy; King, Richard (2004), Selling Spirituality: The Silent Takeover of Religion, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-30209-9.

- Carter, Lewis F. (1987), "The "New Renunciates" of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh: Observations and Identification of Problems of Interpreting New Religious Movements", Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 26 (2), Blackwell Publishing: Pages 148–172, doi:10.2307/1385791, JSTOR 1385791, reprinted in Aveling 1999, pp. 175–218.

- Carter, Lewis F. (1990), Charisma and Control in Rajneeshpuram: A Community without Shared Values, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-38554-7.

- Carus, W. Seth (2002), Bioterrorism and Biocrimes (PDF), The Minerva Group, Inc., ISBN 1-4101-0023-5, retrieved July 12, 2011.

- Dohnal, Cheri (2003), Columbia River Gorge: National Treasure on the Old Oregon Trail (The Making of America series), Arcadia Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7385-2432-0, retrieved September 23, 2011.

- FitzGerald, Frances (September 29, 1986b), "Rajneeshpuram", The New Yorker.

- FitzGerald, Frances (1987), Cities on a Hill: A Journey Through Contemporary American Cultures, New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-671-55209-0. (Includes a 135-page section on Rajneeshpuram previously published in two parts in The New Yorker magazine, Sept. 22 and Sept. 29, 1986 editions.)

- Fox, Judith M. (2002), Osho Rajneesh – Studies in Contemporary Religion Series, No. 4, Salt Lake City: Signature Books, ISBN 1-56085-156-2.

- Gordon, James S. (1987), The Golden Guru, Lexington, MA: The Stephen Greene Press, ISBN 0-8289-0630-0.

- Latkin, Carl A. (1992), "Seeing Red: A Social-Psychological Analysis", Sociological Analysis, 53 (3), Oxford University Press: Pages 257–271, doi:10.2307/3711703, JSTOR 3711703, reprinted in Aveling 1999, pp. 337–361.

- Latkin, Carl A. (1994), "Feelings after the fall: former Rajneeshpuram Commune members' perceptions of and affiliation with the Rajneeshee movement", Sociology of Religion, 55 (1), Oxford University Press: Pages 65–74, doi:10.2307/3712176, JSTOR 3712176, retrieved May 4, 2008

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help).

- Lewis, James R.; Petersen, Jesper Aagaard (eds.) (2005), Controversial New Religions, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-515682-X

{{citation}}:|first2=has generic name (help). - McCormack, Win (1985), Oregon Magazine: The Rajneesh Files 1981–86, Portland, OR: New Oregon Publishers, Inc.. ASIN B000DZUH6E

- Palmer, Susan J.; Sharma, Arvind (eds.) (1993), The Rajneesh Papers: Studies in a New Religious Movement, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1080-5

{{citation}}:|first2=has generic name (help). - Quick, Donna (1995), A Place Called Antelope: The Rajneesh Story, Ryderwood, WA: August Press, ISBN 0-9643118-0-1.

- Richardson, James T. (2004), Regulating Religion: Case Studies from Around the Globe, New York, NY: Luwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, ISBN 0-306-47887-0.

- Shay, Theodore L. (1985), Rajneeshpuram and the Abuse of Power, West Linn, OR: Scout Creek Press. ASIN B0006YPC9O

External links

- The Way of the Heart: A 1984 documentary on Rajneeshpuram – Rajneesh International Foundation; on YouTube

- Rajneeshees in Oregon – The Untold Story. Select government documents, along with a 25-year retrospective by Les Zaitz. The Oregonian, April 2011.

- Rajneeshpuram – 2012 documentary produced by Oregon Public Broadcasting (1 hour)

- Google map of the Big Muddy Ranch property

- University of Oregon video on The Rise and Fall of Rajneeshpuram (c. 2006)

- The Rise and Fall of Rajneeshpuram in Ashé Journal of Experimental Spirituality:

- Religious Movements: Osho (or Rajneeshism)

- John Cramer, "Oregon suffered largest bioterrorist attack in U.S. History, 20 years ago", Bend (Oregon) Bulletin Oct 14, 2001

- Photographs of the "First Annual World Celebration" in Rajneeshpuram, 1982

- Photos of Rajneeshpuram aircraft at Big Muddy Ranch Airport

- Building Oregon: Images of Rajneeshpuram