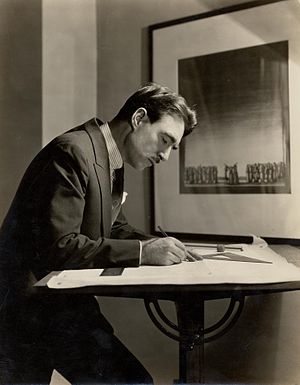

Robert Edmond Jones

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2011) |

Robert Edmond "Bobby" Jones (December 12, 1887 – November 26, 1954) was an American scenic, lighting, and costume designer. He is credited with incorporating the new stagecraft into the American drama. His designs sought to integrate the scenic elements into the storytelling instead of having them stand separate and indifferent from the play’s action. His visual style, often referred to as simplified realism, combined bold vivid use of color and simple, yet dramatic, lighting.

Life

Born in Milton, New Hampshire, Jones attended Harvard University and graduated in 1910. Jones eventually moved to New York (1912) where, with friends made at Harvard, he began to do small design jobs. In 1913 Jones and several friends sailed to Europe to study the new stagecraft with Edward Gordon Craig in Florence. The school in Florence would not accept Jones so he went to Berlin instead, spending a year in informal study with Max Reinhardt’s Deutsches Theater.

For a 1915 production of The Man Who Married a Dumb Wife directed by Harley Granville-Barker, Jones designed a fairly simple set that complemented the action and the other design elements of the production rather than overwhelming it.

His innovative designs for Vladimir Rosing's American Opera Company in 1927 and 1928 were praised by critics.

Jones also brought his expressionistic style to many productions put on by the Theatre Guild, with innovative designs for The Philadelphia Story (1937), Othello (1943), and The Iceman Cometh (1946). Jones’s biggest commercial success was with The Green Pastures (1930), which, if we include its revival in 1951, played for a total of 1,642 performances. This revival was Jones’s last production. Other Broadway credits include Holiday (1928), Mourning Becomes Electra (1931), Ah, Wilderness! (1933), Juno and the Paycock (1940), and Lute Song (1946). Jones was also the production designer for some early three-color Technicolor films, such as La Cucaracha (1934) and Becky Sharp (1935), for which he also designed the costumes.[1]

One of the early members of the Provincetown Players, Jones worked closely with his friend Eugene O'Neill on many of his productions including Anna Christie, The Great God Brown, and Desire Under the Elms.

Jones published many articles on theatre design in the course of his career. His books include Drawings for the Theatre (1925), and The Dramatic Imagination (1941); he also illustrated Kenneth Macgowan's Continental Stagecraft (1922).

His book The Dramatic Imagination is considered the definitive work on modern stage design in the first half of the 20th century.

He died in the house he was born in on Thanksgiving Day, 1954.

Ideas

In a time where theatrical set designs were extravagant and realistic, Jones counteracted the norm by creating simple or expressionistic sets and props. "He was an unashamed pleader for beauty and, far more important, an unsurpassed creator of it." Here follow some of his famous quotations from "The Dramatic Imagination"

"We have learned that beneath the surface of an ordinary everyday normal casual conscious existence there lies a vast dynamic world of impulse and dream, a hinterland of energy which has an independent existence of its own and laws of its own: laws which motivate all our thoughts and our actions."

"[Our playwrights] are attempting to express directly to the audience the unspoken thoughts of their characters, to show us not only the patterns of their conscious behavior but the pattern of their subconscious lives."

"We accept [motion pictures] unthinkingly as objective transcripts of life, whereas in reality they are subjective images of life."

"On stage we shall see the actual characters of the drama; on the screen we shall see their hidden secret selves."

"The theater is a school we shall never have done with studying and learning."

"A stage setting is not a background; it is an environment."

"I think [the theater] needs also actors who have in them a kind of wildness, an exuberance, a take-it-or-leave-it quality, a dangerous quality."

"I am indebted to the great Madame Freisinger for teaching me the value of simplicity in the theater."

"The sole aim of the arts of scene-designing, costuming, lighting, is, as I have already said, to enhance the natural powers of the actor."

"As we work we must seek not for self-expression or for performance for its own sake, but only to establish the dramatist's intention, knowing that when we have succeeded in doing so audiences will say to themselves, not, This is beautiful, This is charming, This is splendid, but--This is true."

References

External links

- Robert Edmond Jones at Internet Broadway Database

- Robert Edmond Jones at IMDB

- Robert Edmond Jones designs and originals, 1913-1943, held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Robert Edmond Jones correspondence, 1930-1941, held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts