Ronald Suresh Roberts

Ronald Suresh Roberts | |

|---|---|

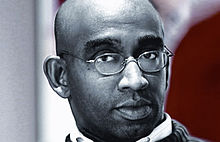

Roberts in 2004 | |

| Born | 17 February 1968 London, UK |

| Alma mater | Balliol College, Oxford, Harvard Law School |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Years active | 1991–present |

| Website | Official website |

Ronald Suresh Roberts (born 17 February 1968), also known as RSR, is a British West Indian biographer, lawyer and writer. He is best known for his biographies of some of the leading figures in the "New South Africa" such as Nobel Prize winner Nadine Gordimer and former South African President Thabo Mbeki. Roberts has been described by Nelson Mandela as "a remarkable and dynamic young man".[1] He currently lives in London, England.

Early life

Roberts was born in Hammersmith, London, to an Afro-Caribbean father and an Indo-Malaysian mother. His parents met while studying law but decided to move back to Roberts father's homeland of Trinidad and Tobago shortly after Roberts birth. It was in Trinidad where Roberts attended Fatima College high school before being accepted into Balliol College, Oxford, and attending on the same Trinidad Government scholarship previously awarded to V. S. Naipaul.[2] He went on to graduate from Harvard Law School in 1991, where he was a classmate of Barack Obama.[3] Roberts’s thesis, “Clarence Thomas and the Tough Love Crowd: Counterfeit Heroes and Unhappy Truths”, was published by New York University Press. His supervisor, Professor Randall Kennedy,[4] taught a Harvard class in “Race Relations and American Law”, which became a flashpoint for ongoing civil rights and campus activism at the time. Obama initially attended the highly polarised class, but did not complete it.[5]

Roberts left a promising career as a Wall Street lawyer to monitor South Africa’s first multiracial elections in 1994.

Life in South Africa

Roberts arrived in South Africa as part of a delegation of international election monitors, and quickly became captivated the uniquely change-making events of the new South African era. He stayed on over two decades and became immersed in the re-architecture of the South African constitution and institutions, especially the new bill of rights. Through his work with ANC Lawyer Kader Asmal, he advocated for and advised upon a broadening of socio-economic rights in the new South African constitution.[6] It was through this work with Kader Asmal that he became involved with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.[7] Asmal, Roberts and Louise Asmal later collected their thoughts in one of the first scholarly discussions of Truth and Reconciliation, entitled Reconciliation through Truth: A Reckoning of Apartheid’s Criminal Governance, a book for which Nelson Mandela wrote the preface.[8] Mandela's Deputy and successor as President, Thabo Mbeki, spoke at the launch of the book in Cape Town.[9]

Roberts then served the Mandela and Mbeki administrations variety of political and technical roles, both developing and defending post-apartheid policies.[10] He was Policy and Strategy Advisor to Asmal[10] in designing water law reforms honoured with the Stockholm Water Prize in 2000, for introducing environmental ethics and post-apartheid equalities.[11]

Biographies

RSRs first biography was of white South African writer and Nobel Laureate Nadine Gordimer.

Roberts first approached Gordimer regarding a biography in 1996 shortly after the completion of his second book, which Gordimer had admired, describing it in a blurb as "blazingly honest, unafraid to be controversial" and "written with verve and elegance".[7] Gordimer agreed to co-operate with the biography, with the condition that she would read the resulting manuscript prior to its publication. After several years of exhaustive interviews and research, Roberts provided Gordimer with a draft; Gordimer objected to Roberts portrayal of her views on Israel, as well as a passage in which Gordimer recounted "making up" a famous anecdote.[12] She also objected to the quoting of derogatory comments Gordimer had made about such prominent South Africans as Ruth First and Doris Lessing. When Roberts refused to compromise, citing journalistic integrity, Gordimer blocked publication of the biography cite.[13]

Publishers Bloomsbury Publishing in London and Farrar, Straus and Giroux in New York subsequently withdrew from the project.[12][14] In letters to RSR both publishers praised the quality of the writing but cited Gordimer's refusal to authorise the biography as their reason not to publish it.[12] Roberts characterized Gordimer's attempts to prevent publication of the biography as censorship[14] and subsequently the manuscript was published by a small South African publisher, which defied Gordimer's threats against it.[13] The saga surrounding the biography was told in a New York Times piece entitled "Nadine Gordimer and the Hazards of Biography".[12] The title of the book, No Cold Kitchen, was a reference to Gordimer's perceived inability to withstand any form of criticism.[15]

Shortly after publishing No Cold Kitchen, Roberts was approached by South African President Thabo Mbeki to write the first authorized account of his intellectual and policy agendas. Called Fit to Govern: The Native Intelligence of Thabo Mbeki, the book was controversial for its insistent post-colonialism and focus on Mbeki as an African leader as opposed to a Western one. In the book Roberts argued that Mbeki's view on the link between HIV and AIDS, was not one of ignorance or denial but scientific curiosity—and that may of the points raised by Mbeki and initially controversial have since entered the orthodoxy.[16]

Current work

Roberts has continued to write for many South African publications on subjects as diverse as politics, book reviews and cultural events. Roberts is known for his challenging viewpoints, indeed in a 2007 column Mail & Guardian editor Ferial Haffajee said Roberts "tests my commitment to freedom of expression".[17] He is Founding Director of Baliol Knowledge, an organisation through which alumni of Balliol College Oxford collaborate impact across the planet.[18]

Controversy

In 2007 the "acutely unpopular and widely reviled"[19] author and AIDS denialist Anthony Brink accused Roberts of using elements of his own unfinished work in Roberts' biography of Mbeki. Roberts countered that Brink had no relevant research given that as late as 2005 Brink remained a "complete stranger to the president at a personal level".[20]

In 2006 Leslie Weinkove, Acting Judge of the Western Cape High Court judgement, found against Roberts in a defamation case Roberts instituted against the South African newspaper The Sunday Times. The judgement gives detailed descriptions of his behaviour in dealing with a complaint against the South African Broadcasting Corporation.[21] Roberts' response to the judgement was published in an extensive interview in the South African Mail & Guardian, which cites a suppressed letter from Ken Owen, a previous editor of the The Sunday Times, which recognised The Times′ "eagerness to smear Ronald Roberts" and repudiated the words the newspaper had attributed to him, adding that "I must say that on matters within my knowledge [its] reporting is false".[22]

In 2007 the same newspaper incorrectly placed Roberts, Christine Qunta and others in a group of 12 signatories to an article supposedly supporting Aids denialism. Roberts complained and the Times issued a retraction and apology to the group. Roberts accepted the apology but maintained that the newspaper's conduct was "shameful but not surprising." [23]

In popular culture

Roberts's work has formed the subject of at least one play and one novel.

His dispute with Nadine Gordimer, and its significance as an emblem of the broader cultural tensions in South Africa's post-apartheid transformations, is the subject of the play The Imagined Land by Craig Higginson,[24] the editor of Robert's Gordimer biography.[25]

The same issue forms the inspiration for Absolution by Patrick Flannery, 'an inquiry into the ethical accountability of the writer and the ethical and epistemological problems of "life-writing"'.[26]

The dispute is also covered by Dame Hermione Lee, President of Wolfson College, Oxford, in Biography: A Very Short Introduction.[27]

References

- ^ "Ronald Suresh Roberts". www.ronaldsureshroberts.com. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "Profile - Ronald Roberts", Beyond THE GREY SHIRT (Fatima Old Boys’ Association Newsletter), p. 5.

- ^ "Obama joins list of seven presidents with Harvard degrees", Harvard Gazette, 6 November 2008.

- ^ "Randall L. Kennedy, Michael R. Klein Professor of Law", Harvard Law School.

- ^ David Remnick (7 May 2010). The Bridge: The Life and Rise of Barack Obama. Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-330-53160-3.

- ^ "Prepare Now For The Second Revolution", Mail & Guardian, 30 September 1994.

- ^ a b Reconciliation through Truth: A Reckoning of Apartheid's Criminal Governance

- ^ Reconciliation through Truth, pp. 1–6.

- ^ Antjie Krog, Country of My Skull.

- ^ a b Naomi Klein, "Beware electocrats", Radical Philosophy 150 (July/August 2008).

- ^ "Kader Asmal, South Africa", SIWI, 2000.

- ^ a b c d Rachel Donadio, "Nadine Gordimer and the Hazards of Biography", The New York Times, 31 December 2006.

- ^ a b Ronald Roberts, "Censorship, beyond any crying of it", Financial Times, 25 June 2005. As pdf:

- ^ a b Rory Carroll, "Nobel writer Gordimer, champion of free speech, is accused of censorship", The Guardian, 7 August 2004.

- ^ Kevin Bloom, "Assange the (would-be) Censor: Uncensored", Daily Maverick, 24 September 2011.

- ^ "LETTER: Mbeki, HIV/AIDS and memory", Business Day live, 2 June 2014.

- ^ Ferial Haffajee, "How dare he?", Thought Leader, Mail & Guardian, 15 November 2007.

- ^ http://www.balliolknowledge.com/about/ronald-roberts/

- ^ Kamini Padayachee, "Aids dissident loses job battle", IOL, 25 September 2014.

- ^ Ronald Suresh Roberts,"Aids denialist Brink’s loony letter to Mbeki", Thought Leader, Mail & Guardian, 28 November 2007. For the full article see Fit to Govern: The Native Intelligence of Thabo Mbeki.

- ^ "Roberts v Johncom Media Investments Limited" (8677/04) [2007] ZAWCHC 1 (8 January 2007). South Africa: Western Cape High Court, Cape Town.

- ^ Fikile-Ntsikelelo Moya, "'I'm like Oscar Wilde'", Mail & Guardian, 26 January 2007.

- ^ "Sunday paper apologises to Qunta, Roberts", IOL, 8 October 2007.

- ^ Sam Mathe. "New play looks at souring of a literary collaboration". African Independent. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Roberts, Ronald (2005). No Cold Kitchen. Johannesburg, South Africa: STE Publishing. ISBN 9781919855585.

- ^ Leo Robson (29 March 2012). "Absolution | No Time Like the Present". New Statesman. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Lee, Hermione (2009). Biography: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199533541.