Royal Palace of Mari

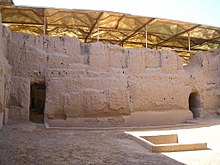

The remains of the royal palace of Mari | |

| Location | Mari, Eastern Syria |

|---|---|

| Type | Dwelling |

| Part of | Acropolis |

| Area | 2.5 hectares (6.2 acres) |

| History | |

| Material | Stone |

| Founded | 24th century BC, last major renovation c.1800 BC.[1] |

| Periods | Bronze – Hellenistic |

| Associated with | Yasmah-Adad, Zimrilim |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Partial restoration |

| Public access | No |

| Active excavation | |

The Royal Palace of Mari was the royal residence of the rulers of the ancient kingdom of Mari in eastern Syria. Situated centrally amidst Palestine, Syria, Babylon, Levant, and other Mesopotamian city-states, Mari acted as the “middle-man” to these larger, powerful kingdoms.[2] Both the size and grand nature of the palace demonstrate the importance of Mari during its long history, though the most intriguing feature of the palace is the nearly 25,000 tablets found within the palace rooms.[3] The royal palace was discovered in 1935, excavated with the rest of the city throughout the 1930s, and is considered one of the most important finds made at Mari[4] André Parrot led the excavations and was responsible for the discovery of the city and the palace. Thousands of clay tablets were discovered through the efforts of André Bianquis, which provided archaeologists the tools to learn about, and to understand, everyday life at the palace and in Mari.[5] The discovery of the tablets also aided in the labeling of various rooms in terms of their purpose and function.[6]

Overview

| Mari |

|---|

|

| Kings |

| Archaeology |

The palace reached its grandest state with its last renovation under king Zimri-Lim in the 18th century BC; in addition to serving as the home of the royal family, the palace would have also housed royal guards, state workers, members of the military, and those responsible for the daily activities of the kingdom.[7] The apartments of the king were well separated from the rest of the palace and relatively simple to identify when Parrot led the excavations.[8] While most rooms in the palace were interconnected and allowed access to one another, the private quarters of the royal family were very isolated. Parrot emphasized the amount of privacy afforded the king and his family, as well as the maximum level of security that was maintained through the architecture of the building.[8]

An entry gate was the only access point of the large palace complex, thus providing added security. The layout of the palace was also built with the security of the royal family in mind. A central court was surrounded by a series of smaller rooms. Entryways to courtyards were positioned in such a way as to make any attacks on those within the courtyard nearly impossible.[9] Such architectural features did not allow any visitor to peer directly into one of the open courts, but forced a visitor to change direction and enter on the side of the court; anyone wishing to use a weapon would not have been able to directly access any room inside of the main gateway.[9]

The royal palace at Mari was decorated with frescoes and statues. Decoration different depending on the function of the room.[10] Religious and royal scenes were placed in public areas, where the message of kingship and religion could easily be viewed by visitors and residents of the palace.[10] More private rooms, like the royal apartments, were decorated with patterns, shapes, and geometric designs.[10] Designs in the royal apartments would have added to the luxurious accommodations befitting the royal family, while the representational frescoes would have demonstrated luxury, power, and authority.

Archaeological finds

Statues

Statues of gods and past rulers were the most common among statues unearthed at the Palace of Zimri-Lin. The title of Shakkanakku (military governor) was borne by all the princes of a dynasty who reigned at Mari in the late third millennium and early second millennium BC. These kings were the descendents of the military governors appointed by the kings of Akkad.[11] Statues and sculpture were used to decorate the exterior and interior of the palace. Zimri-Lin used these statues to connect his kingship to the gods and to the traditions of past rulers. Most notable of these statues are the statue of Iddi-Ilum, Ishtup-Ilum, the Statue of the Water Goddess, and Puzur-Ishtar.

Puzur-Ishtar

The statue of Puzur-Ishtar once stood in one of the sanctuaries of the Palace of Zimri-Lim, but was discovered in the museum of Nebuchadrezzar’s palace at Babylon (604-562 B.C.E). The inscription on the hem of the statue’s skirt mentions Puzur-Ishtar, sakkanakku of Mari, and also mentions his brother the priest Milaga.[12] Horned caps are usually limited to divine representations in Mesopotamian art but they do not occur on depictions of kings during the Ur III period, therefore it is considered that perhaps the horns of divinity on Puzur-Ishtar’s cap qualified him (to the Babylonian soldiers) as a god to be carted home as the ultimate symbol of their victory over the people of Mari.[13]

Ishtup-Ilum

The Statue of Ishtup-Ilum is made of basalt and was found in room 65 of the palace. The inscription on his shoulder identifies this man as a governor (sakkanakku) of Mari during the early second millennium B.C.E. Ishtup-Ilum was known for his lavish gifts to the Ishtar temple, the temple of the popular goddess of fertility, love, war, and sex. The height of the statue is 1.52 meters. The statue is now in the Aleppo Museum.[13]

Iddi-Ilum

Iddi-Ilum was a former sakkanakku of Mari. This statue portrays Iddi-Ilum as a religious ruler, for his hands are clasped in front of him in the typical Mesopotamian pose of prayer. His luxurious robe has a tasseled border and is wound around his body, contrary to Mesopotamian tradition. The statuette bears an inscription in Akkadian: “Iddi-Ilum, shakkanakku of Mari, has dedicated his statue to Inanna. Whosoever erases this inscription will have his line wiped out by Inanna.” Connections can be made between this statuette and the statue of Puzur-Ishtar, also shakkanakku of Mari, by virtue of the trimmed beard and rich garments.[14]

Statue of a Water Goddess

Depictions of water bearing goddesses were a common occurrence in Mesopotamia. The statue of a Goddess holding a vase was in fact a fountain, with water flowing out of the vase. This statue is nearly life size and most likely stood in the palace chapel. A channel connected to a water supply was drilled through the body of the statue and allowed water to flow from the goddess’ vase.[15]

Tablets

More than 20,000 tablets have been found in the palace.[16] The tablets, according to André Parrot, "brought about a complete revision of the historical dating of the ancient Near East and provided more than 500 new place names, enough to redraw or even draw up the geographical map of the ancient world"[17]

Many of the recovered tablets have been identified as either the remains of the royal epistolary archive of Mari, other administrative documents, and the Kings letters to his wives which were found in the women's quarters. Some letters include direct quotes from King Hammurabi leading us to believe that they were contemporaneous with his rule.[18]

Other letters shed light on divinity at Mari and in the ancient Near East. Letters from the epistolary archive include fascinating information about divination, gods, and even descriptions of ancient dreams. According to the tablets, a prophetic dream was had, a letter would be sent to a diviner who would perform extispicy to confirm the revelation.[19]

Frescoes

Figural frescoes were found in five rooms within the Palace of Mari. From those recovered, only four compositions were able to be restored,[20] due to the deterioration of the materials and damage done by Hammurabi of Babylon's sacking of Mari circa 2760 BCE. the date here is a misprint for ca. 1760 bce. (middle chronology) [21][22]

The Investiture of Zimri-Lim

"The Investiture of Zimri-Lim," dating to the 18th century BCE and discovered during 1935–1936 excavations at Mari by French archaeologist André Parrot, was the only painting found in situ in the palace. The painting is distinguished in part by its wide range of color, including green and blue. Painted on a thin layer of mud plaster applied directly to the palace's brick wall, the scene features a warrior goddess, likely Ishtar, giving Zimri-Lim a ring and a staff, the symbols of kingship. The continuation of the red and blue painted border of the panel suggests that it was one of several adorning the walls of the room.[20]

Recent restoration efforts by the Louvre have revealed previously unseen details, such as scalloping on Zimri-Lim's robe, and unexpectedly vibrant colors, such as a brilliantly orange bull.[22]

Sacrifical procession scene

Fragments of a sacrificial procession scene were found at the base of the eastern half of the same wall on which "The Investiture of Zimri-Lim" was recovered. The painting has multiple registers and depicts a life-size figure leading men who are in turn leading a procession of sacrificial animals. The colors utilized are black, brown, red, white, and gray.[20]

The application technique of this scene differs from the thin mud plaster used as a base for other frescoes in the palace. The sacrificial procession scene utilized layered mud, which was scored to aid attachment to a top layer of thick gypsum plaster. The presence of both frescoes in the same room and the better preservation of the "Investiture" scene could mean that "Investiture" was an earlier painting, and that the concealing of this fresco by the later procession scene is what saved it from suffering the same degree of damage as the palace's other frescoes.[20]

"Audience chamber" frescoes

A number of wall-painting fragments were also discovered in from the south-western end of narrow room that Parrot dubbed the "king's audience chamber." These fragments were restored to a size of 2.8 meters (nearly ten feet) in height and 3.35 meters (nearly eleven feet) in width.[20]

The paintings include two major registers, each depicting a scene in which offerings are made to deities. The scenes are framed by mythological creatures and bordered top and bottom by striding men carrying bundles on their backs. The figures are outlined with thick black line, with red, gray, brown, yellow, and white pigments utilized throughout the painting.[20]

Other fragmentary images

Painting fragments found in the same room as the "Investiture of Zimri-Lim" and the sacrificial procession scene include goats in heraldic pose flanking a tree, a life-size figure with a dagger in his belt, a figure in front of an architectural background, and a hand grasping hair in a manner very similar to the traditional Egyptian scene of a king smiting an enemy with a mace.[20]

Others rooms yielded very fragmentary wall paintings, which may have fallen and broken partly as a result of the collapse of an upper story. The fragments fall into two general stylistic groups: figures resembling the bundle-bearing men in the "audience chamber" frescoes, and life-size figures bearing similarity to the sacrificial procession scene.[20]

References

- ^ Peter M. M. G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC). p. 286.

- ^ Malamat 1989, pp. 2.

- ^ Malamat 1989, pp. 6.

- ^ Kuhrt, 1997, p.102.

- ^ Parrot, 1955, pg. 24-5.

- ^ Burney, 1977, pg. 92-3.

- ^ Parrot 1955, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Parrot 1955, pp. 23.

- ^ a b Burney 1977, pp. 94.

- ^ a b c Burney 1977, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Louvre. "The Statuette of Iddi-Ilum," Department of Near Eastern Antiquities: Mesopotamia. Accessed December 1, 2014. http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/statuette-iddi-ilum

- ^ Gates, Henriette-Marie. "The Palace of Zimri-Lim at Mari." The Biblical Archaeologist 47 (June.,1984): 70-87.

- ^ a b Gates, "The Palace of Zimri-Lim at Mari," 70-87.

- ^ Louvre. "Statuette of Iddi-Ilum," Department of Near Eastern Antiquities: Mesopotamia. Accessed December 1, 2014. http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/statuette-iddi-ilum

- ^ Wiess, Harvey. "From Ebla to Damascus: Art and Archaeology of Ancient Syria." Archaeology 38 (September/October 1985): 58-61.

- ^ Robson, 2008, p.127.

- ^ Sasson, Jack M. (October–Dec 1998). "The King and I a Mari King in Changing Perceptions". Journal of the American Oriental Society 118 (4): pp. 453–470. doi:10.2307/604782..

- ^ Wolfgang, p.4

- ^ Wolfgang, p.209

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gates, Marie-Henriette . “The Palace of Zimri-Lim at Mari.” The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 47, No. 2 (Jun., 1984), pp. 70-87.

- ^ J. R. Krupper, "Mari," in Reallexikon der Assyriologie, vol. 7, p. 389. Hammurapi probably occupied Mari in the 32nd year of his reign

- ^ a b Louvre. “Mural Painting, Department of Near Eastern Antiquities: Mesopostamia.” Accessed November 28th, 2014. http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/mural-painting

Sources

- Burney, Charles (1977). The Ancient Near East. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801410802.

- Gates, Henriette (1984). "The Palace of Zimri-Lim at Mari". The Biblical Archaeologist. 47 (2): 70–87. doi:10.2307/3209888.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (1997). Ancient Near East C. 3000-330 BC. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-16763-5.

- Malamat, Abraham (1989). Mari and the Early Israelite Experience. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0197261170.

- "Mural Painting, Department of Near Eastern Antiquities: Mesopotamia". Louvre. Retrieved November 28, 2014.

- Parrot, André (1955). Discovering Buried Worlds. Philosophical Library, Inc. ISBN 978-0548450956.

- Robson, Eleanor (2008). Mathematics in ancient Iraq: a social history. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09182-2.

- Sasson, Jack (1998). "The King and I: A Mari King in Changing Perceptions". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 118 (4): 453–470. doi:10.2307/604782.