SMS Hela

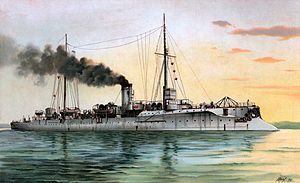

Painting of Hela in 1902

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Template:Sclass- |

| Succeeded by | Template:Sclass- |

| Built | 1893–95 |

| In commission | 3 May 1896 – 13 Sept. 1914 |

| Completed | 1 |

| Lost | 1 |

| History | |

| Name | Hela |

| Builder | AG Weser, Bremen |

| Laid down | 1893 |

| Launched | 28 March 1895 |

| Commissioned | 3 May 1896 |

| Fate | Sunk 13 September 1914 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Displacement | 2,082 t (2,049 long tons) |

| Length | 105.0 m (344 ft 6 in) overall |

| Beam | 11.0 m (36 ft 1 in) |

| Draft | 4.64 m (15 ft 3 in) |

| Propulsion | 2 shaft triple expansion, 6000 ihp |

| Speed | 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) |

| Range | 3,000 nmi (5,600 km; 3,500 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

SMS Hela was an aviso of the German Imperial Navy prior to and during World War I. The only ship of her class, Hela was launched on 28 March 1895 in Bremen. She was named after the Hela peninsula near Danzig (present-day Gdańsk). In 1899 she was re-classified to a light cruiser, although she was lightly armed for a light cruiser. Hela's main armament consisted of just four 8.8-centimeter (3.5 in) guns.[1]

In 1900–1901, Hela was deployed to China during the Boxer Rebellion. She participated in extensive fleet maneuvers in 1902, before being significantly rebuilt from 1903–1906. From 1910, Hela was used as a fleet tender. With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, she was put back into active service as a support ship for the torpedo boats stationed off Helgoland. On 13 September 1914, Hela was torpedoed and sunk by the British submarine HMS E9; two of her crew died.[2]

Design

Hela was the culmination in the development of the aviso type in the Imperial German Navy. German avisos were developed from earlier torpedo boats and were intended for use in home waters with the fleet. The first aviso, Zieten, was purchased from a British shipbuilder in 1875;[3] seven more ships were built in German yards before Hela was laid down in 1893.[4] The aviso type culminated in what would later be referred to as the light cruiser; Hela's successors, the Template:Sclass-s, were the first true light cruisers built.[3]

General characteristics and machinery

Hela was 104.6 meters (343 ft 2 in) long at the waterline and 105 m (344 ft 6 in) overall. She had a beam of 11 m (36 ft 1 in) and a draft of 4.46 m (14 ft 8 in) forward and 4.64 m (15 ft 3 in) aft. She was designed to displace 2,027 t (1,995 long tons), and at full combat load the displacement increased to 2,082 t (2,049 long tons). Her hull was constructed with transverse and longitudinal steel frames, which contained 22 watertight compartments above the armored deck and ten below. A double bottom ran for 35 percent of the length of the hull. Hela's crew consisted of 7 officers and 171 enlisted men.[2]

The ship was powered by two 3-cylinder triple expansion engines; both drove a screw that was 3.25 m (10 ft 8 in) in diameter. Each engine had its own separate engine room. The engines were supplied with steam by six locomotive boilers split into two boiler rooms. The engines were rated at 6,000 indicated horsepower and a top speed of 20 kn (37 km/h; 23 mph), though on trials they reached a half knot better. Hela was equipped with three electrical generators that produced 36 kilowatts at 67 volts. Steering was controlled by a single rudder.[2]

Armament and armor

Hela was armed with four 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/30[Note 1] quick-firing guns in individual mountings.[2] The guns fired 7 kg (15 lb) projectiles[5] at a muzzle velocity of 590 meters per second (1,936 f/s) and a rate of approximately 15 shots per minute. At the maximum elevation of 30°, the guns could hit targets out to 10,500 m (11,480 yards).[6] These guns were provided with a total of 800 rounds, for 200 per gun. She was also equipped with six 5 cm (2.0 in) SK L/40 quick-firing guns.[2] These guns fired 1.75 kg (3.9 lb) shells, at up to 10 shots per minute. They had a maximum range of 6,200 m (6,780 yd). Hela carried 250 rounds per gun.[7] Her armament was completed with three 45 cm (18 in) torpedo tubes. Two were placed on the deck and the third was submerged in the bow of the ship.[2]

Hela was lightly armored. She was protected by an armor deck that was 20 mm (0.79 in) thick and composed of steel. The deck sloped on the sides, and was slightly increased in thickness to 25 mm (0.98 in). The conning tower was armored with 30 mm (1.2 in) thick steel.[2]

Service history

In early 1898, Hela was assigned to the I Division of the Maneuver Squadron for that year's training exercises. She served as the dispatch vessel for the four Template:Sclass-s.[8]

Boxer Rebellion

During the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, Chinese nationalists laid siege to the foreign embassies in Peking and murdered Baron Clemens von Ketteler, the German minister.[9] The widespread violence against Westerners in China led to a creation of an alliance between Germany and seven other Great Powers: the United Kingdom, Italy, Russia, Austria-Hungary, the United States, France, and Japan.[10] Those soldiers who were in China at the time were too few in number to defeat the Boxers;[11] in Peking there was a force of slightly more than 400 officers and infantry from the armies of the eight European powers.[12] At the time, the primary German military force in China was the East Asia Squadron, which consisted of the protected cruisers Kaiserin Augusta, Hansa, and Hertha, the small cruisers Irene and Gefion, and the gunboats Jaguar and Iltis.[13] There was also a German 500-man detachment in Taku; combined with the other nations' units the force numbered some 2,100 men.[14]

These 2,100 men, led by the British Admiral Edward Seymour, attempted to reach Peking but due to heavy resistance were forced to stop in Tientsin.[15] As a result, the Kaiser determined an expeditionary force would be sent to China to reinforce the East Asia Squadron. Hela was part of the naval expedition, which included the four Template:Sclass- pre-dreadnought battleships, sent to China to reinforce the German flotilla there.[16] Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz opposed the plan, which he saw as unnecessary and costly.[17] The force was sent in spite of von Tirpitz's objections; it arrived in China in September 1900. By that time, the siege of Peking had already been lifted.[18] As a result, the task force suppressed local uprisings around Kiaochow. In the end, the operation cost the German government more than 100 million marks.[17]

Fleet training, 1902

On 31 August 1902, the annual fleet maneuvers began. The first portion of the exercise positioned Germany in a naval war against a powerful enemy that had superior forces in the North and Baltic Seas. A German squadron, consisting of the coastal defense ships Hagen, Heimdall, and Hildebrand and a division of torpedo boats were trapped in the Kattegat by a superior enemy unit in the North Sea. The German squadron was tasked with returning to Kiel in the Baltic, where it would return to Wilhelmshaven via the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal to rejoin the rest of the fleet. Hela, along with three Brandenburg-class battleships and the cruisers Nymphe and Amazone, was positioned in one of the three main channels from the Kattegat to Kiel to act as an opposing force. Two other battle squadrons were positioned to block the advance of the isolated German squadron.[19]

On the morning of 2 September, the operation commenced.[19] Hela was tasked with sweeping the numerous smaller channels, inlets, and bays in the squadron's area of responsibility. At 06:00 that morning, the commander of the German squadron decided to take his ships through the channel to which Hela was assigned.[20] The "hostile" torpedo-boat screen sighted the German flotilla, but a dense fog precluded effective pursuit by the battleships.[21] However, Hela, the other two cruisers, and the torpedo boats were detached to engage the German torpedo-boat screen. Hela and the other ships quickly "destroyed" several of the German torpedo boats. This prompted the German squadron to retreat northward, with Hela and the other ships in pursuit. The German squadron was chased back through the Kattegat before the exercise was called off. On the night of 3 September, the entire fleet anchored off Læsø island to give the crews a rest.[22]

The following day, 4 September, the exercise resumed. The German squadron was reinforced by several battleships and the armored cruiser Prinz Heinrich; Hela was again assigned to the hostile force. The German flotilla was ordered to sail into the North Sea and attempt to reach the safety of the island fortress of Helgoland. Hela was assigned to a screening force that was intended to intercept the German squadron so it could be brought to battle. A short engagement between the hostile screen and Prinz Heinrich ensued, during which Prinz Heinrich damaged the protected cruisers Freya and Victoria Louise. A torpedo boat attack on the German squadron followed in the early hours of 5 September.[22] The hostile force was unable to prevent the escape of the German squadron, however, which reached Helgoland by 12:00.[23]

Hela and the rest of the fleet anchored off Helgoland on 8–11 September. During the day the ships conducted training with steam tactics. On 11 September the ships returned to Wilhelmshaven where on the following two days the ships replenished their coal supplies. On 14 September the final operation of the annual maneuvers began. The situation specified that the naval war had gone badly for Germany; only four battleships were still in service, along with Hela, Freya, and a division of torpedo boats. The ships were to be stationed in the mouth of the Elbe river to protect the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal and access to Hamburg.[24] On 15 September, the hostile force blockaded the Elbe, along with other rivers and harbors on the North Sea. The torpedo boats, which had been scattered in the previous engagement, were tracked and destroyed by the hostile force. The hostile battleship squadron steamed to the mouth of the Elbe, where Hela, Freya, and the remaining torpedo boats were stationed as lookouts.[25] Nothing happened during the day of 16 September, but that night several German torpedo boats managed to destroy one of the blockading cruisers and badly damage another.[26] The following day, Prinz Heinrich engaged Hela and Freya briefly before forcing the two ships to retreat. The weather began to storm so the operation was postponed until the following day. That morning, the hostile fleet forced its way into the Elbe, past the fortifications at the mouth of the river. The German flotilla made a desperate attack which resulted in the sinking of two of the hostile battleships. The hostile force, however, ultimately overwhelmed the outnumbered German ships and the exercise ended with their victory.[27]

Reconstruction and later service

In 1903, Hela was taken into the dry dock at the Kaiserliche Werft Danzig for extensive modernization.[2] The ship's superstructure was rebuilt, and her two rear 8.8 cm guns were removed.[28] Her boilers, which had been trunked into a single smoke stack were now split between two funnels. Coal storage capacity was also increased, from 370 t (360 long tons) to 412 t (405 long tons). The ship was also further subdivided; the 22 watertight compartments above the armored deck were increased to 30, and the double bottom was extended to cover 39 percent of the hull. She was also re-boilered; her six original boilers were replaced with eight Marine-type boilers.[2] Work lasted until 1906, at which point she rejoined the fleet and was stationed in Germany. Her crew was also increased by the addition of another officer and 16 enlisted men.[28] After 1910, Hela was withdrawn from active service and used as a fleet tender.[2]

World War I

When World War I broke out, Hela was brought back to active duty and assigned to the covering forces for the German torpedo boats that formed the outer ring of coastal scouting patrols in the German portion of the North Sea. Hela was stationed to the northeast of Helgoland, along with the cruiser Stettin.[29] These forces were surprised and attacked by superior British forces on 28 August 1914 in the first Battle of Helgoland Bight.[30] After reports of the initial engagement between light forces reached Hela, the ship turned westward to join the fighting. However, after another report, which stated that the British ships were retreating to the southwest away from Helgoland, reached Hela, the ship returned to her patrol station.[31] Hela emerged from the battle without damage, and that night regrouped with the cruisers Kolberg and München to provide cover for the remaining torpedo boats and reestablish the Bight patrol line.[32]

However, two weeks later, on the morning of 13 September 1914, Hela was attacked six miles southwest of Helgoland by the British submarine HMS E9 under command of the future Admiral Max Horton.[33] Hela was conducting a training exercise at the time; the area around Helgoland was presumed safe from British submarines.[34] After surfacing, E9 spotted the German cruiser and immediately re-submerged to fire two of her torpedoes. After 15 minutes, E9 rose to periscope depth to inspect the scene. The British submarine found Hela sinking. Within another 15 minutes, Hela had slipped beneath the waves.[35] The crew of E9 was awarded a bounty of £1,050 as a reward for sinking Hela.[36] Despite the speed with which the ship sank, her entire crew, with the exception of two sailors, were rescued from the sea.[2]

Hela was the first German ship sunk by a British submarine in the war.[37] As a result of her loss, all German ships conducting training exercises were moved to the Baltic Sea to prevent further such sinkings.[34] One of her 8.8 cm guns was retrieved from the wreck and is now preserved at Fort Kugelbake in Cuxhaven.[38]

Notes

- Footnotes

- Citations

- ^ Hildebrandt, Röhr, & Steinmetz, vol. 4, p. 108

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Gröner, p. 99

- ^ a b Gardiner, Chesneau, & Kolesnik, p. 249

- ^ Gardiner, Chesneau, & Kolesnik, pp. 256–258

- ^ Friedman, N. (2011). Naval weapons of World War One. p. 276

- ^ DiGiulian, Tony (22 March 2007). "German 8.8 cm/30 (3.46") SK L/30 8.8 cm/30 (3.46") Ubts L/30". Navweaps.com. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ^ DiGiulian, Tony (21 June 2008). "German 5 cm/40 (1.97") SK L/40 5 cm/40 (1.97") Tbts KL/40". Navweaps.com. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ^ Naval Notes, p. 483

- ^ Bodin, pp. 5–6

- ^ Bodin, p. 1

- ^ Holborn, p. 311

- ^ Bodin, p. 6

- ^ Harrington, p. 29

- ^ Bodin, p. 11

- ^ Bodin, pp. 11–12

- ^ Brassey, p. 74

- ^ a b Herwig, p. 103

- ^ Sondhaus, p. 186

- ^ a b R.U.S.I. Journal, p. 91

- ^ R.U.S.I. Journal, p. 92

- ^ R.U.S.I. Journal, pp. 92–93

- ^ a b R.U.S.I. Journal, p. 93

- ^ R.U.S.I. Journal, p. 94

- ^ R.U.S.I. Journal, pp. 94–95

- ^ R.U.S.I. Journal, p. 95

- ^ R.U.S.I. Journal, pp. 95–96

- ^ R.U.S.I. Journal, p. 96

- ^ a b Gardiner, Chesneau, & Kolesnik, p.258

- ^ Osborne, p. 56

- ^ Osborne, p. 60

- ^ Osborne, pp. 76–77

- ^ Osborne, p. 102

- ^ Halpern, p. 33

- ^ a b Gunton, p. 28

- ^ The Independent p. 9

- ^ Proceedings, p. 1338

- ^ Thomas, p. 130

- ^ Mehl, p. 79

References

- Bodin, Lynn E. (1979). The Boxer Rebellion. London: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85045-335-5.

- Brassey, Thomas Allnutt (1901). Brassey's Annual: The Armed Forces Yearbook. London: W. Clowes.

- Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger; Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-133-5.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-790-9. OCLC 22101769.

- Friedman, N. (2011). Naval weapons of World War One. Yorkshire: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Gunton, Michael (2005). Submarines at War: A History of Undersea Warfare from the American Revolution to the Cold War. New York City: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7867-1455-1.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4. OCLC 57447525.

- Harrington, Peter (2001). Peking 1900: The Boxer Rebellion. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-181-7.

- Herwig, Holger (1980). "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst, New York: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Hildebrandt, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert; Steinmetz, Hans-Otto, eds. (1981). Die deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien–ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart. Herford: Koehlers Verlagsgesellschaft mbH. ISBN 3-7822-0497-2.

- Holborn, Hajo (1982). A History of Modern Germany: 1840–1945. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00797-7.

- Mehl, Hans (2002). Naval Guns: 500 Years of Ship and Coastal Artillery. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-557-8.

- "Naval Notes". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. XLII. London: J. J. Keliher & Co.: 467–487 1898. doi:10.1080/03071849809417364.

- Osborne, Eric W. (2006). The Battle of Heligoland Bight. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34742-8.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval warfare, 1815–1914. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21478-0.

- Thomas, Lowell (2002). Raiders of the Deep. Garden City, New York: Periscope Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-904381-03-7.

- "The Story of the Week". The Independent. 90. New York: Independent Publications, Inc.: 7–11 1914.

- "Naval War Notes". Proceedings. 43. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute: 1313–1349. 1917.

- "German Naval Manoeuvres". R.U.S.I. Journal. 47. London: Royal United Services Institute for Defence Studies: 90–97. 1903.

54°03′N 07°55′E / 54.050°N 7.917°E