The Silent Command

| The Silent Command | |

|---|---|

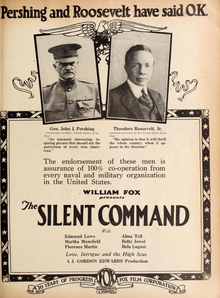

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | J. Gordon Edwards |

| Written by | Anthony Paul Kelly Rufus King |

| Produced by | William Fox |

| Starring | Edmund Lowe Bela Lugosi |

| Cinematography | George W. Lane |

| Distributed by | Fox Film Corporation |

Release date |

|

Running time | 8 reels |

| Country | United States |

| Language | Silent (English intertitles) |

The Silent Command is a 1923 American silent drama film directed by J. Gordon Edwards featuring Bela Lugosi as a foreign saboteur in his American film debut. The film, written by Anthony Paul Kelly and Rufus King, also stars Edmund Lowe, Alma Tell, and Martha Mansfield. Shot in New York, The Silent Command began Lugosi's career in the American film industry.[1][2] The film's focus on his eyes, at times in extreme close-up, helped to establish his image for later roles.

The film depicts the story of Benedict Hisston (Lugosi), who is part of a plot to destroy the Panama Canal. Initially unable to obtain necessarily intelligence from Richard Decatur (Lowe), a captain in the United States Navy, he enlists the aid of femme fatale Peg Williams (Mansfield). Decatur pretends to be seduced into the conspiracy, costing him his career and estranging him from his wife (Tell), but he ultimately betrays the saboteurs in Panama and stops their plan. He returns home to the Navy and his wife, and to popular acclaim for his heroics.

The film was produced in cooperation with the Navy and was intended as a propaganda film to encourage support for a larger navy. The Silent Command was shown at the opening of several Fox Theatres locations and was sometimes marketed in conjunction with naval recruitment efforts. It received generally positive reviews from contemporary film critics, although modern appraisals consider the film mediocre.

Unlike most Fox Film productions of the silent era, several copies of The Silent Command have survived. It has been released in multiple home video formats, and is now in the public domain and available online.

Plot

[edit]Benedict Hisston is a foreign agent, part of a conspiracy to destroy the Panama Canal and the US Navy's Atlantic Fleet. He attempts to acquire information about mine placement in the Canal Zone from Captain Richard Decatur but fails. That information is essential to the conspiracy's success and so he then hires vamp Peg Williams to obtain the intelligence through seduction.

Decatur is not fooled and obeys the "silent command" of the Chief of Naval Intelligence to play along with the spies without revealing his purpose to friends or family. He is court-martialed, stripped of rank, and dismissed from the Navy after he strikes an admiral. His association with Williams estranges him from his wife but earns him the trust of Hisston and the other spies. When the conspirators are ready to enact their plan, he travels to Panama with them. He thwarts their attempt at sabotage, saving the canal and the fleet. He is then reinstated into the Navy, reunited with his wife, and honored by the nation for his heroism.[1][2]

Cast

[edit]- Edmund Lowe as Captain Richard Decatur

- Alma Tell as Mrs. Richard Decatur

- Martha Mansfield as Peg Williams

- Betty Jewel as Dolores

- Florence Martin as Williams's maid

- Bela Lugosi as Benedict Hisston (miscredited as Belo Lugosi)[3]

- Carl Harbaugh as Menchen

- Martin Faust as Cordoba

- Gordon McEdward as Gridley

- Byron Douglas as Admiral Nevins

- Theodore Babcock as Admiral Meade

- George Lessey as Mr. Collins

- Warren Cook as Ambassador Mendizabal

- Henry Armetta as Pedro

- Rogers Keene as Jack Decatur

- J.W. Jenkins as the Decatur's butler

- Kate Blancke as Mrs. Nevins

- Elizabeth Mary Foley as Jill Decatur[3][4]

Production

[edit]

Rufus King, later known for his detective novels,[5] wrote the original story for The Silent Command, which was adapted into a screenplay by Anthony Paul Kelly.[4] It was intended as a propaganda film to encourage popular support for expansion of the United States Navy[6][7] and was made with the Navy's cooperation and support.[6][4] Fox Film's publicity promoter, Wells Hawks, may have been responsible for this arrangement, as he had previously worked in a publicity role for the Navy.[6] Quotes praising the film were provided by several prominent members of the military for use in advertising, including General John J. Pershing and Theodore Roosevelt Jr., the Assistant Secretary of the Navy.[6] Years later, in a publicity interview for The Return of Chandu, Bela Lugosi commented on the irony of being a propagandist for naval expansion when his native country, landlocked Hungary, "has no navy nor needs any!"[7]

In December 1922, Lugosi had starred in a Greenwich Village play, The Red Poppy. The play performed poorly, but Lugosi, in the role of a thuggish Spaniard, received critical praise.[8] He was cast as Hisston in The Silent Command based on the strength of that performance.[9] Extreme close-ups of Lugosi's eyes were used throughout the film to reinforce perception of this character as evil.[10] Film historian Gary Rhodes traced the origin of this technique, intended to suggest the evil eye or hypnosis, to characters in Weimar cinema inspired by Svengali.[10] Lugosi had played one such character, Professor Mors, in the 1919 German film Sklaven fremdes Willens;[10][11] Edwards himself had portrayed Svengali in a run of Trilby on the St. Louis stage.[12]

The Silent Command was released in at least two editions. As shown at its New York premiere, it was an eight-reel film with a 91-minute run time. However, the version screened earlier in Chicago had been 18 minutes shorter, which reduced the film to seven reels;[13] this cut was used for most subsequent releases.[3][4] H.T. Hodge claimed to have shown a nine-reel version at the Palace Theatre in Abilene, Texas.[14] Additionally, some prints were released as part-color films with tinted scenes.[6][15]

The Silent Command was also released internationally, including Australia and Cuba in 1924,[16][17] and was retitled His Country for distribution in France.[6]

Release and reception

[edit]

In 1923, William Fox was expanding his Fox Theatres chain of movie theaters. The Silent Command was shown at the opening or re-opening of several such locations. On August 25, 1923, the first Fox Theatre on the Pacific opened in Oakland, California.[a] The Silent Command was the first feature-length film screened at the Fox Oakland,[18][19] during an elaborate opening gala that also included Tom Mix riding Tony, the Wonder Horse into the theater. Attendees included members of the film industry, city officials from Oakland and San Francisco, and faculty and students from the University of California, Berkeley[19][20] The following week, on August 31, it was also the first film shown at the grand opening of Fox's Monroe Theatre in Chicago, in an invitation-only showing involving studio executives and members of the film industry.[21] To encourage attendance at further showings at the Monroe, the studio partnered with the Navy's local recruitment office to produce one-sheets encouraging men to see the film before enlisting.[22] In Springfield, Massachusetts and St. Louis,[b] it was also the debut film shown at theaters re-opening after renovations.[25][26]

Despite the earlier showings in Oakland and Chicago, Fox advertised the film's world premiere at New York's Central Theatre on September 2.[27][28] As part of the Navy's support for the film, the audience included Rear Admiral Charles Peshall Plunkett and other officers.[29] The film played at the Central for four weeks before being replaced with Monna Vanna.[30]

The Silent Command was generally praised by contemporary reviewers. Laurence Reid and C. S. Sewell, writing for Motion Picture News and Moving Picture World respectively, both offered acclaim for the film, despite what Reid described as a slow start.[31][32] Variety was slightly less complimentary, suggesting the film was better suited for "regular neighborhood" theaters than prestigious first-run houses and criticizing the cinematography in Mansfield's vamp scenes.[13] Most newspaper critics also gave positive reviews,[33][34] although the Evening Journal wrote that the plot "taxes the credulity of even a generous picture fan."[34] Modern reviews have been less enthusiastic. Lugosi biographer Arthur Lennig considered the film "turgid",[35] and AllMovie awarded it 2+1⁄2 out of 5 stars.[36]

Legacy

[edit]

The Silent Command was Lugosi's first American film, and influenced the direction of his career in cinema.[2] Lugosi had expressed an interest in playing Latin lover characters in the model of Rudolph Valentino, but his performance as Hisston revealed him to be convincing in more villainous roles.[37] According to Rhodes, critics considered the focus on Lugosi's eyes cliché or even unintentionally humorous, but some filmgoers did find the shots genuinely frightening.[38] This technique, showing Lugosi's eyes in extreme close-up, would be revisited in many of his later films,[9][39] such as The Midnight Girl, Dracula, and White Zombie.[10][40] Images of Lugosi's eyes were eventually even used in advertising.[39]

Unlike most of Edwards's films,[41][42] copies of The Silent Command are preserved in three archives: the George Eastman Museum, the Department of Film at the Museum of Modern Art, and Brussels's Cinematek.[43] Grapevine Video made the film available on VHS in 1999,[44] and released a DVD edition in 2005.[45] On January 1, 2019, the film entered the public domain in the United States and became freely available at the Internet Archive.[46]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ This theater, later renamed the Orpheum, is distinct from the Fox Oakland Theatre opened in 1928.[18]

- ^ This theater, later renamed the Sun,[23] is distinct from the Fox Theatre opened in 1929.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Rhodes 1997, pp. 74–75.

- ^ a b c Lennig 2003, pp. 42–43.

- ^ a b c Rhodes 1997, p. 74.

- ^ a b c d "The Silent Command". AFI Catalogue of Feature Films: The First 100 Years 1893–1993. American Film Institute. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ Kabatchnik 2010, p. 353.

- ^ a b c d e f Rhodes 1997, p. 75.

- ^ a b Lugosi, Bela (1934). "Bela Lugosi welcomes romantic role of "Chandu" after being 'typed' as 'heavy'". The Return of Chandu (pressbook). Publicity. Principal Distributing Corporation: 1.

- ^ Bordman 1995, p. 196.

- ^ a b Rhodes 1997, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Rhodes 2001, p. 30.

- ^ Mank 2009, p. 626.

- ^ "Charlotte Walker next at Suburban". The St. Louis Star. 27 (9447): 9. June 15, 1910.

- ^ a b Fred [pseud.] (September 6, 1923). "The Silent Command". Variety. 72 (3): 23.

- ^ Hodge, H.T. (January 26, 1924). "The Silent Command". Exhibitors Herald. 18 (5): 66.

- ^ "The return of Lugosi". Famous Monsters of Filmland (100): 52–60. 1973.

- ^ "Fox films abroad". Exhibitors Herald. 18 (10): 40. March 1, 1924.

- ^ "Elaborate list of specials scheduled by Fox for Brazil". Exhibitors Herald. 18 (12): 61. March 15, 1924.

- ^ a b Tillmany & Dowling 2006, p. 47.

- ^ a b "Fox opens coast house in Oakland". Motion Picture News. 28 (10): 1182. September 8, 1923.

- ^ "Fox opening Oakland Theatre acquires continental chain". Moving Picture World. 64 (2): 130. September 8, 1923.

- ^ Mason, L. H. (September 1, 1923). "Chicago and the Mid-West". Motion Picture News. 28 (9): 1043.

- ^ "Recruiting tie-up boosts 'The Silent Command'". Motion Picture News. 28 (11): 1325. September 15, 1923.

- ^ Bryant, Time (June 7, 2013). "Lawrence Group will give Sun Theater an $11 million makeover". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ Tebbe, Jen (January 31, 2017). "Origin story: The Fabulous Fox". Missouri Historical Society. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ Smith, Sumner, ed. (September 8, 1923). "Exhibitors' news and views". Moving Picture World. 64 (2): 136.

- ^ "New season opens with bang at St. Louis film theatres". Moving Picture World. 64 (3): 240. September 15, 1923.

- ^ "Five specials on Fox September list". Motion Picture News. 28 (9): 1034. September 1, 1923.

- ^ "Two Fox premieres due in New York". Motion Picture News. 28 (9): 1098. September 1, 1923.

- ^ "A great array on Broadway". Motion Picture News. 28 (11): 1304. September 15, 1923.

- ^ "'Mona Vana' at Central". Variety. 72 (5): 20. September 20, 1923.

- ^ Sewell, C. S. (September 15, 1923). "The Silent Command". Moving Picture World. 64 (3): 264–265.

- ^ Reid, Laurence (September 15, 1923). "The Silent Command". Motion Picture News. 28 (11): 1335.

- ^ "Fox makes 1923 debut on Broadway with opening of big productions". Moving Picture World. 64 (3): 273. September 15, 1923.

- ^ a b "'The Silent Command'–Fox Central". The Film Daily. 25 (57): 4. September 7, 1923.

- ^ Lennig 2003, p. 45.

- ^ "The Silent Command". AllMovie. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ Bojarski 1980, p. 22.

- ^ Rhodes 2001, p. 132.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2001, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Weiss, Ron (1975). "Lugosi: the man and the vampire". Quasimodo's Monster Magazine (3): 34–45.

- ^ Solomon 2011, p. 1.

- ^ Brownlow 1976, p. 35.

- ^ "The Silent Command / Edmund Lowe [motion picture]". American Silent Feature Film Database. Library of Congress. October 8, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ The Silent Command. Online Computer Library Center. OCLC 52544481 – via WorldCat.

- ^ "The Silent Command". Silent Era. Silent Era Films on Home Video. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Evans, Rachel (January 8, 2019). "23 from '23: Celebrating the growth of the public domain with digital exhibits & silent film screenings". A Library with a View. Alexander Campbell King Law Library. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bojarski, Richard (1980). Films of Bela Lugosi. Citadel Press. ISBN 978-0-8065-0716-3.

- Bordman, Gerald (1995). American Theatre: A Chronicle of Comedy and Drama, 1914–1930. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509078-9.

- Brownlow, Kevin (1976) [1968]. The Parade's Gone By.... University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03068-8.

- Kabatchnik, Amnon (2010). Blood on the Stage 1925–1950: Milestone Plays of Crime, Mystery, and Detection. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6963-9.

- Lennig, Arthur (2003). The Immortal Count: The Life and Films of Bela Lugosi. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2273-1.

- Mank, Gregory William (2009) [1990]. Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff: The Expanded Story of a Haunting Collaboration (Revised ed.). McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-3480-0.

- Rhodes, Gary D. (1997). Lugosi: His Life in Films, on Stage, and in the Hearts of Horror Lovers. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-2765-9.

- Rhodes, Gary D. (2001). White Zombie: Anatomy of a Horror Film. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-2762-8.

- Solomon, Aubrey (2011). The Fox Film Corporation, 1915–1935: A History and Filmography. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-6286-5.

- Tillmany, Jack; Dowling, Jennifer (2006). Theatres of Oakland. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-4681-0.

External links

[edit]- The Silent Command at AllMovie

- The Silent Command at IMDb

- The Silent Command is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive (79 min)

- 1923 films

- 1923 drama films

- 1920s spy drama films

- American spy drama films

- American propaganda films

- American silent feature films

- American black-and-white films

- Films directed by J. Gordon Edwards

- Fox Film films

- Surviving American silent films

- 1920s American films

- Silent American drama films

- Films about the United States Navy