Somatotype and constitutional psychology

This article may be unbalanced toward certain viewpoints. (June 2019) |

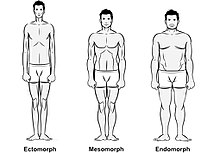

Somatotype is a taxonomy developed in the 1940s by American psychologist William Herbert Sheldon to categorize the human physique according to the relative contribution of three fundamental elements which he termed "somatotypes". He named these after the three germ layers of embryonic development: the endoderm, (which develops into the digestive tract), the mesoderm, (which becomes muscle, heart and blood vessels) and the ectoderm (which forms the skin and nervous system).[1] His initial visual methodology has been discounted as subjective and largely discredited, but later formulaic variations of the methodology, developed by his original research assistant Barbara Heath, and later Lindsay Carter and Rob Rempel are still in academic use.[2][3][4]

Constitutional psychology is a now neglected theory, also developed by Sheldon in the 1940s, which attempted to associate his somatotype classifications with human temperament types.[5][6] The foundation of these ideas originated with Francis Galton and eugenics.[2] Sheldon and Earnest Hooton were seen as leaders of a school of thought, popular in anthropology at the time, which held that the size and shape of a person's body indicated intelligence, moral worth and future achievement.[2]

In his 1954 book, Atlas of Men, Sheldon categorized all possible body types according to a scale ranging from 1 to 7 for each of the three "somatotypes", where the pure "endomorph" is 7–1–1, the pure "mesomorph" 1–7–1 and the pure "ectomorph" scores 1–1–7.[7][8][9] From type number, an individual's mental characteristics could supposedly be predicted.[8] Barbara Honeyman Heath, who was Sheldon's main assistant in compiling Atlas of Men, accused him of falsifying the data he used in writing the book.[2]

The three types

Sheldon's "somatotypes" and their associated physical and psychological traits were characterized as follows:[3][9]

- Ectomorphic: characterized as skinny, thin, slender, slim, lithe, lanky, neotenous, flat-chested, lightly muscled, weak, fragile, delicate, and usually tall; described as intelligent, contemplative, melancholic, industrious, effeminate, submissive, inferior, perfectionist, quirky, idiosyncratic, sensitive to pain, soft, gentle, loving, helpful, placatory, calm, peaceful, vulnerable, humble, self-deprecatory, socially awkward, solitary, secretive, concealing, self-conscious, introverted, shy, reserved, defensive, uncomfortable, tense, and anxious.[3][7][9][10]

- Mesomorphic: characterized as hard, rugged, triangular, muscular, thick-skinned, and with good posture; described as athletic, eager, adventurous, willing to take risks, competitive, extroverted, aggressive, masculine, macho, authoritative, strong, assertive, direct, forthright, blustering, dominant, tough, strict, fortunate, vigorous, energetic, determined, courageous, and ambitious.[3][7][9]

- Endomorphic: characterized as fat, round, heavy, usually short, and having difficulty losing weight; described as open, outgoing, sociable, amiable, friendly, affectionate, accepting, happy, pleased, satisfied, laid-back, easily complacent, lazy, ungenerous, selfish, greedy, well-endowed, and slow to react.[3][7][9]

Stereotyping

There is evidence that different physiques carry cultural stereotypes. For example, one study found that endomorphs are likely to be perceived as slow, sloppy, and lazy. Mesomorphs, in contrast, are typically stereotyped as popular and hardworking, whereas ectomorphs are often viewed as intelligent, yet fearful.[11]

Heath-Carter Formula

Though the psychological bindings have largely been neglected, Sheldon's physical taxonomy has persisted, particularly the Heath-Carter variant of the methodology.[12] This formulaic approach utilises an individual's weight (kg), height (cm), upper arm circumference (cm), maximal calf circumference (cm), femur breadth (cm), humerus breadth (cm), triceps skinfold (mm), subscapular skinfold (mm), supraspinal skinfold (mm), and medial calf skinfold (mm), and remains popular in anthropomorphic research, as to quote Rob Rempel "With modifications by Parnell in the late 1950s, and by Heath and Carter in the mid 1960s somatotype has continued to be the best single qualifier of total body shape".[13]

This variant utilizes the following series of equations to assess a subject's traits against each of the three somatotypes, each assessed on a seven-point scale, with 0 indicating no correlation and a 7 a very strong:

- Endomorphy: =

- where:

- Mesomorphy: =

- Ectomorphy : Calculate the subjects Ponderal Index:

- If , Ectomorphy =

- If , Ectomorphy =

- If , Ectomorphy =

This numerical approach has gone on to be incorporated in the current sports science and physical education curriculums of numerous institutions, ranging from the UK's secondary level GCSE curriculums (14- to 16-year-olds), the Indian UPSC Civil Service exams, to MSc programs worldwide, and has been utilized in numerous academic papers, including:

- Rowing athletes[14]

- Tennis athletes[15]

- Judo athletes[16]

- Volleyball athletes[17]

- Gymnasts[18][19]

- Soccer athletes[20][21]

- Triathletes[22]

- Han people[23]

- Persons with diabetes[24][25]

- Taekwondo athletes[26]

- Persons with eating disorders[27]

- Dragon boat participants[28]

Criticism

Sheldon's ideas that body type was an indicator of temperament, moral character or potential—while popular in an atmosphere accepting of the theories of eugenics—were soon widely vilified.[2][29]

The principal criticism of Sheldon's constitutional theory was that it was not a theory at all but one general assumption, continuity between structure and behavior, and a set of descriptive concepts to measure physique and behavior in a scaled manner.[3]

His use of thousands of photographs of naked Ivy League undergraduates, obtained without explicit consent, from a pre-existing program evaluating student posture, has been described as scandalous, and perverted ("the study of nude people by lewd people").[2][30]

His original visual assessment methodology, based on the photographs, has also been criticized as subjective.[2][3][4]

His original thesis has also been described as fraudulent for knowingly failing to acknowledge/account for body shape changing with age.[2]

His suggestion of a genetic link to both body shape and personality traits has also been described as objectional.[4]

Sheldon's work has also been criticized as being heavily burdened by his own stereotypical and discriminatory views.[2][5]

While popular in the 1950s,[30] Sheldon's claims have been dismissed by modern scientists, calling them "outdated" or "quackery".[3][4][5][31][32][33]

See also

- Biological anthropology

- Body mass index

- Body shape

- Eugenics in the United States

- Female body shape

- Kinanthropometry

- Neurobiological effects of physical exercise

- Physiognomy

- The Bell Curve

References

- ^ Hollin, Clive R. (2012). Psychology and Crime: An Introduction to Criminological Psychology. Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 0415497035.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Vertinsky, P (2007). "Physique as destiny: William H. Sheldon, Barbara Honeyman Heath and the struggle for hegemony in the science of somatotyping". Canadian Bulletin of Medical History. 24 (2): 291–316. PMID 18447308. Archived from the original on 2015-09-11.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Roeckelein, Jon E. (1998). "Sheldon's Type Theory". Dictionary of Theories, Laws, and Concepts in Psychology. Greenwood. pp. 427–8. ISBN 9780313304606.

- ^ a b c d Genovese, JEC (2008). "Physique correlates with reproductive success in an archival sample of delinquent youth" (PDF). Evolutionary Psychology. 6 (3): 369–85. doi:10.1177/147470490800600301.

- ^ a b c Rafter, N (2008). "Somatotyping, antimodernism, and the production of criminological knowledge". Criminology. 45 (4): 805–33. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2007.00092.x.

- ^ "Constitutional Theory". The Penguin Dictionary of Psychology. Penguin. 2009. ISBN 9780141030241 – via Credo Reference.

- ^ a b c d Mull, Amanda (2018-11-06). "Americans Can't Escape Long-Disproven Body Stereotypes". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2018-12-31.

- ^ a b Sheldon, William Herbert (1954). Atlas of Men: A Guide for Somatotyping the Adult Male at All Ages. New York: Harper.

- ^ a b c d e Kamlesh, M.L. (2011). "Ch. 15: Personality and Sport § Sheldon's Constitutional Typology". Psychology in Physical Education and Sport. Pinnacle Technology. ISBN 9781618202482.

- ^ "What Is Your Body Type?". 2014-04-24. Retrieved 2018-12-31.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Ryckman, RM; Robbins, MA; Kaczor, LM; Gold, JA (1989). "Male and female raters' stereotyping of male and female physiques". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 15 (2): 244–51. doi:10.1177/0146167289152011.

- ^ Norton, Kevin; Olds, Tim (1996). Anthropometrica: A Textbook of Body Measurement for Sports and Health Courses. Australian Sports Commission; UNSW Press. ISBN 978-0868402239.

- ^ Rempel, R (1994). "A Modified Somatotype Assessment Methodology". Simon Fraser University. ISBN 978-0-612-06785-1.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Kerr, D; Ross, WD; Norton, K; Hume, P; Kagawa, Masaharu (2007). "Olympic Lightweight and Open Rowers possess distinctive physical and proportionality characteristics for selecting elite athletes". Journal of Sports Sciences. 25 (1): 43–53. doi:10.1080/02640410600812179.

- ^ Sánchez‐Muñoz, C; Sanz, D; Mikel Zabala, M (November 2007). "Anthropometric characteristics, body composition and somatotype of elite junior tennis players". Br J Sports Med. 41 (11): 793–799. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2007.037119. PMC 2465306.

- ^ Lewandowska, J; Buśko, K; Pastuszak, A; Boguszewska, K (2011). "Somatotype Variables Related to Muscle Torque and Power in Judoists". Journal of Human Kinetics. 30: 21–28. doi:10.2478/v10078-011-0069-y.

- ^ Papadopoulou, S (January 2003). de Ridder, H.; Olds, T. (eds.). "Anthropometric characteristics and body composition of Greek elite women volleyball players". Kinanthropometry VII (7 ed.). Pochefstroom University for CHE: 93–110.

- ^ Purenović-Ivanović, T; Popović, R (April 2014). "Somatotype of Top-Level Serbian Rhythmic Gymnasts". Journal of Human Kinetics. 40 (1): 181–187. doi:10.2478/hukin-2014-0020. ISSN 1899-7562.

- ^ Irurtia Amigó, Alfredo (2009). "Height, weight, somatotype and body composition in elite Spanish gymnasts from childhood to adulthood". Apunts Med Esport. 61: 18–28.

- ^ Adhikari, A; Nugent, J (2014). "Anthropometric characteristic, body composition and somatotype of Canadian female soccer players". American Journal of Sports Science. 2 (6–1): 14–18.

- ^ Petroski (2013). "Anthropometric, morphological and somatotype characteristics of athletes of the Brazilian Men's volleyball team: an 11-year descriptive study". Brazilian Journal of Kineanthropometry & Human Performance. 15 (2): 184.

- ^ Leake, Christopher N.; Carter, JE (1991). "Comparison of body composition and somatotype of trained female triathletes". Journal of Sports Sciences. 9 (2): 125–135. doi:10.1080/02640419108729874.

- ^ Yang, LT (2015). "Study on the adult physique with the Heath-Carter anthropometric somatotype in the Han of Xi'an, China". Anat Sci Int. 91: 180–7. doi:10.1007/s12565-015-0283-0. PMID 25940679.

- ^ Baltadjiev, AG (2013). "Somatotype characteristics of female patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus". Folia Med (Plovdiv). 55: 64–9. doi:10.2478/folmed-2013-0007. PMID 23905489.

- ^ Baltadjiev, AG (2012). "Somatotype characteristics of male patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus". Folia Med (Plovdiv). 54: 40–5. doi:10.2478/v10153-011-0087-5. PMID 23101284.

- ^ Noh; et al. (2013). "Somatotype analysis of elite Taekwondo athletes compared to non-athletes for sports health sciences". Toxicology and Environmental Health Sciences. 5 (4): 189–196. doi:10.1007/s13530-013-0178-1.

- ^ Stewarta; et al. (2014). "Somatotype: a more sophisticated approach to body image work with eating disorder sufferers". Advances in Eating Disorders: Theory, Research and Practice. 2 (2): 125–135. doi:10.1080/21662630.2013.874665.

- ^ Pourbehzadi; et al. (2012). "The Relationship between Posture and Somatotype and Certain Biomechanical Parameters of Iran Women's National Dragon Boat Team". Annals of Biological Research. 3 (7): 3657–3662.

- ^ "Body Type". Encyclopedia of Special Education: A Reference for the Education of Children, Adolescents, and Adults with Disabilities and Other Exceptional Individuals. Wiley. 2007. ISBN 9780471678021 – via Credo Reference.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Rosenbaum, Ron (January 15, 1995). "The great ivy league nude posture photo scandal". The New York Times. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ^ Zentner, Marcel; Shiner, Rebecca L. (2012). Handbook of Tempermaent. Guilford. p. 6. ISBN 9781462506514.

- ^ Ryckman, Richard M. (2007). Theories of Personality (9th ed.). Cengage Learning. pp. 260–1. ISBN 9780495099086.

- ^ "Nude photos are sealed at Smithsonian". The New York Times. January 21, 1995. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

Sources

- Gerrig, Richard; Zimbardo, Phillip G. (2002). Psychology and Life (16th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 0-205-33511-X.

- Hartl, Emil M.; Monnelly, Edward P.; Elderkin, Roland D. (1982). Physique and Delinquent Behavior (A Thirty-year Follow-up of William H. Sheldon’s Varieties of Delinquent Youth). New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-328480-5.

Further reading

- Sheldon, William H. (1942). The Varieties of Temperament. New York; London: Harper & Brothers. Archived from the original on 2012-02-24 – via University of Delhi.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Carter, J.E. Lindsay; Heath, Barbara Honeyman (1990). Somatotyping-development and Applications. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521351170.

- Arraj, Tyra; Arraj, James. "Ch. 4:William Sheldon's Body and Temperament Types". Tracking the Elusive Human. Vol. Vol. I. Midland, OR: Inner Growth. ISBN 0914073168 – via innerexplorations.com.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Coughlan, Robert (June 25, 1951). "What manner of morph are you?". Life. Vol. 30, no. 26. pp. 65–79 – via Google Books.

![{\displaystyle {\text{PI}}={\frac {height[cm]}{(mass[kg])^{1/3}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/eaf7f78cc8c1bd78c65483befaef02ada91b7164)