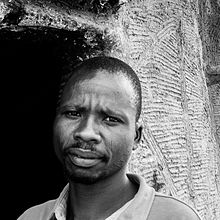

Somba people

The Somba people, also called Ditamari, are an African ethnic group found primarily in northwestern Benin and northern Togo.[1] The name is a generic term for the Betammaribe and related peoples, who make up about 8% of Benin’s population.[2] Their language is the "Ditammari language", also known as Tamberma, and it is a northern branch of the Niger-Congo family of languages.[3]

The Somba people are known for their traditional body scarring rituals, starting between the age of two and three.[4] These special marks are a form of lifelong identification marks (tattoo ID), which identify a person as belonging to one's tribe as well as more coded personal information. Additional marks are added at puberty, readiness for marriage, post-child birth as a form of visible communication. These scars range from some on the face, to belly and back.[4][5]

They are regionally famous for their distinctive house construction style called the Tata Somba. It consists of a ground floor which houses a kitchen and livestock owned by the family, the upper floor or roof designed to dry grains and to sleep.[1] These castle-shaped houses also integrated their traditional spiritual beliefs, and their aim to protect themselves and animal life from natural and supernatural dangers.[6][7] These homes may have developed as a means to resist night raids during the era when slave hunters in West Africa roamed to kidnap their victims for sale.[8][9]

The castle-style homes of the Somba people are known as Takienta in the Koutammakou region of Togo. The uniqueness and sophistication of this architecture has been recognized since 2004 by UNESCO as a world heritage site, with the statement, "Koutammakou is an outstanding example of territorial occupation by a people in constant search of harmony between man and the surrounding nature".[10] The residences of the Somba people have become an attraction in the fledgling tourist industry of Benin and Togo.[8]

They are especially found in towns such as Nikki and Kandi that were once Bariba kingdoms and in Parakou in mid-eastern Benin. However, there is also a significant population of Somba in northwest Benin in the Atacora region in cities such as Natitingou and a number of villages. Many Somba in the northwest have migrated to the east. In Parakou the Guema market was founded by a Somba tribe who migrated from Atacora, and it specializes in beef and pork and local millet beer known as choukachou.[citation needed]

References

- ^ a b Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford University Press. p. 403. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

- ^ "Somba (people)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ Ditammari: A language of Benin, Ethnologue

- ^ a b Margo DeMello (2014). Inked: Tattoos and Body Art around the World. ABC-CLIO. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-1-61069-076-8.

- ^ Trojanowska, Alicja (1992), Scarification among the Somba people from Atakora mountains, Smithsonian Institution

- ^ a b Tony Allan; Fergus Fleming; Charles Phillips (2012). African Myths and Beliefs. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-1-4488-5989-4.

- ^ Dossa, Luc Hippolyte; et al. (2015). "The indigenous Somba cattle of the hilly Atacora region in North-West Benin: threats and opportunities for its sustainable use". Tropical Animal Health and Production. 48 (2). Springer Science: 349–359. doi:10.1007/s11250-015-0958-5.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help) - ^ a b Stuart Butler (2006). Benin. Bradt. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-84162-148-7.

- ^ Cynthia Jacobs Carter (2008). Freedom in My Heart: Voices from the United States National Slavery Museum. United States National Slavery Museum, National Geographic. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-1-4262-0127-1.

- ^ Koutammakou, the Land of the Batammariba, UNESCO (2004)