Spillings Hoard

| Spillings Hoard | |

|---|---|

A part of cache No 2 of the Spillings Hoard in the Gotland Museum | |

| |

| Material | Silver, Bronze |

| Size | 40 kg (88 lb) plus 27 kg (60 lb) plus 20 kg (44 lb) |

| Created | 9th century |

| Period/culture | Viking Age (late Iron Age) |

| Discovered | 16 July 1999 Spillings, Othem, Gotland, Sweden 57°43′18″N 18°46′49″E / 57.721608°N 18.780352°E |

| Discovered by | Jonas Ström and Kenneth Jonsson |

| Present location | Gotland Museum |

| Identification | 52803 |

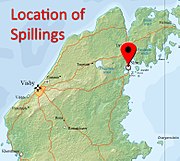

The Spillings Hoard (Swedish: Spillingsskatten) is the world's largest Viking silver treasure, found on Friday 16 July 1999 in a field at the Spilling farm northwest of Slite, on northern Gotland, Sweden. The silver hoard consisted of two parts with a total weight of 67 kg (148 lb) before conservation and consisted of, among other things, 14,295 coins most of which were Islamic from other countries. A third deposition containing over 20 kg (44 lb) of bronze scrap-metal was also found. The three caches had been hidden under the floorboards of a Viking outhouse sometime during the 9th century.

Discovery

On Friday 16 July 1999, a team of reporters from the Swedish television TV4 were in the socken of Othem on Gotland to film a cultural feature from Almedalen Week. They chose to do a segment on the problem with looting of archaeological sites with archaeologist Jonas Ström acting as their guide along with Kenneth Jonsson, a professor of numismatics, who happened to be on the island at that time.[1] Spillings farm was selected for the filming since about 150 silver coins and bronze objects had been found there earlier by the landowner Björn Engström.[2]

With filming complete, Ström and Jonsson decided to continue their survey of the field. Twenty minutes after the TV-crew had left, they heard a strong signal from their metal detector, which led them to the smaller of the two silver caches. A couple of hours later and only 3 metres (9.8 ft) from the first find, they received another signal from the detector:[3]

"The display blinked 'overload' and then it turned itself off."

— Jonas Ström[3]

The site was hurriedly cordoned off, back-up crew from the museum was sent for, permission for an archaeological excavation was immediately sought at the County Administrative Board and guards were posted. However, instead of keeping the find a secret, the Gotland Museum decided to go public with the find immediately. During the first weekend, over 2,000 people visited the excavation site.[4]

Some days later, the metal detector indicated a third metal cache approximately 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) from the first find. The archaeologists concentrated on uncovering the two first finds before starting with the third. Due to the size of the hoards and the fragility of the objects, the bottom layers of the depositions were encapsulated in plaster. Only when they tried to lift the finds out of the soil did the archaeologists realize how heavy the hoards were. The smaller weighed 27 kg (60 lb) and the larger one 40 kg (88 lb). An attempt to X-ray the finds at the local hospital failed because they contained so much silver that the X-ray plates remained blank.[5]

The larger find was intact but the smaller had been damaged by a plough. A previous landowner who visited the excavation commented that he had found metal wires around the find-spot several years earlier, but thinking that they were only steel wire, he had thrown them away. It was therefore concluded that the treasure had originally been even larger.[6]

With the two first caches taken care of, the third deposition was excavated almost a year after the first discovery. It contained over 20 kg (44 lb) of bronze scrap-metal, most of which had been partially melted into a 'cake'. This find was deemed even more valuable since very few finds contain such large amounts of bronze intended for smelting.[6]

Further excavations

Additional excavations were conducted in the summer of 2000 and in 2003-06. Remnants of wood, iron rivets and mounts as well as a lock mechanism were found, leading to the conclusion that the caches had been stored in chests.[7]

An extended survey and excavation revealed the foundations of a building and indicated that the hoards had been placed under the floorboards of what would probably have been a warehouse, shed or storage rather than a dwelling since it had no hearth. Carbon dating showed that the building had been in use between 540 and 1040.[8] The foundations and the remaining postholes indicated a regular Viking Age structure, about 10 by 15 m (33 by 49 ft) with a slanting sedge-covered roof, much like other similar finds on Gotland. It had been built on an older Iron Age foundation.[9]

Find

The silver deposits were roughly square-shaped with rounded corners, about 40 cm to 45 cm × 50 cm (16 in to 18 in × 20 in), suggesting that they had been in sacks of cloth, leather or pelt, inside boxes or chests of wood.[4] In the bronze deposit were found substantial pieces of wood and iron, such as fittings, ironwork, nails and a lock-device, showing that the bronze had been kept in a sturdy chest. A carbon dating of the chest dated it to approximately 675, making it older than the objects stored inside it.[10]

Although silver hoards and treasures are not unusual on Gotland, this was an exceptionally large find. One explanation may be found in the location near some of the island's best and most significant harbours during the Viking Age. The silver in the caches would have been enough to pay the tax to the Swedish king for all of Gotland for five years.[11]

The following surveys and excavations of the fields surrounding the find-site showed that the site had been inhabited continuously over 1,000 years up until the 19th century. Over 700 more objects were retrieved, such as objects of bronze and copper, fired clay, clothes pins, a piece of glass, tile pieces, chains, needles, glass beads, slag, iron nails, polished semi-precious stones and brick.[12]

The Spillings Hoard is the world's largest Viking silver treasure.[13] A finder's fee of SEK 2,091,672 (approx. US$242,400) was paid to the landowner for the treasure, although the real value of it is much higher. It was the largest amount of money ever paid for a find in Sweden, according to director of the Swedish National Heritage Board Sven Göthe.[14] The hoard was dated to have been hidden some time after 870–71.[4] The treasure is on permanent display in the Gotland Museum.[15]

As of 2015[update], more than 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb) of silver from over 700 caches deposited between the 9th and 12th centuries have been found on Gotland. This includes 168,000 silver coins from the Arab world, North Africa and Central Asia.[16]

Silver depositions

The caches contained silver objects ranging from coins, bars, thread and hacksilver to be used as raw material, to jewelry such as fingerings, bangles and pendants. Much of the material had been bundled up to correspond with the mark-weight system of the Viking Age, in which 200 grams (0.44 lb) made one mark.[17]

Almost 60% of the find consisted of 486 bangles or parts thereof, making it the largest ever find of such silver jewellery as of 2015[update]. Most of the bracelets weighed around 100 grams under the mark-weight system and were of traditional Gotlandic design, a number of them have very detailed ornamentation.[18] There were also bangles of British and Western Scandinavian design as well as plain, undecorated fingerings of Finnish and British design, known as ring money.[19]

Of the 14,295 coins found, 14,200 were Islamic dirhams,[20] four were Nordic (from Hedeby), one was Byzantine and 23 were from Persia. The earliest, a Persian coin, dates from 539 and the latest from 870.[2] Many of the coins (as well as the bangles) had marks that may have been made when the purity of the silver was tested.[21] There were several imitations and fakes among the coins. The illegal copies were made from good silver, but made in other places than where the originals were minted. All in all, 69 different minting locations from 15 present-day countries were identified in the hoard.[22]

During the conservation work of the larger hoard (No 2) it became evident that the larger objects had been placed at the bottom of the cache and the smaller ones, ending with the cut coins, had been strewn on top.[23]

Moses coin

One of the most noted coins in the hoard, dated to c. 800,[24] is from the Khazar Kingdom and designated the "Moses Coin". According to written sources the Khazars are believed to be Jews, but few objects have been found to support this claim.[2] The coin is inscribed with "Moses is the messenger of God" instead of the usual Muslim text "Muhammad is the messenger of God".[25]

Bronze deposition

Excavated in the same manner as the silver hoards, the bronze cache was encapsulated on site and transported to the Gotland Museum for further examination. The objects were removed layer after layer from top to bottom until the large melted 'cake', about 40 cm (16 in) in diameter was uncovered. Most of the bronze objects were broken, fragmented or partially melted, suggesting that they were kept in the heartwood chest to be used as raw material for new artifacts. Individual finds consisted of parts of, and some complete, necklaces, bangles, fingerings, pins for clothes and mounts for drinking horns. The bronze objects span a period of 200–300 years and are mostly of Baltic origin or possibly Russian with only a few of them Scandinavian. Even though several scholars have been involved in identifying the deposition, no consensus have been reached regarding why the hoard was collected or the dating of it. Two theories are that it was either the stock of a foundryman living on Gotland, or booty from a Viking raid that was hidden under the floor of the outhouse.[26]

Gallery

-

Silver melted into bars from hoard No 2.

-

Silver tangle from hoard No 1. This one weighs about 2000 gram, about 10 silver marks in the old Gotlandic system where silver was used as currency.

-

Closeup of silver coins from hoard No 2.

-

Iron fittings from the chest in the bronze cache.

See also

- Havor Hoard

- Cuerdale Hoard

- Silverdale Hoard

- Sundveda Hoard

- Molnby Hoard

- Vale of York Hoard

- Mildenhall Treasure

References

- ^ Pettersson 2009, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Lynn, Jonathan (26 June 2002). "Biggest Viking Hoard Unveiled". www.themoscowtimes.com. The Moscow Times. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ a b Reistad, Helena (14 June 2002). "Silverskörd. Vi har tre månader på oss att se världens största vikingatida silverskatt – sedan åker den tillbaka till Gotland" [Silver harvest. We have three months to see it – after that it goes back to Gotland]. www.dn.se (in Swedish). Dagens Nyheter. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ a b c Pettersson 2009, p. 16.

- ^ Pettersson 2009, pp. 16–18.

- ^ a b Pettersson 2009, p. 18.

- ^ Pettersson 2009, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Pettersson 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Pettersson 2009, p. 47.

- ^ Pettersson 2009, p. 32.

- ^ Pettersson 2009, pp. 20–24.

- ^ Pettersson 2009, pp. 34–36.

- ^ "Skatten från Spillings i Othem socken-världens största vikingatida silverskatt" [The Hoard from Spillings in Othem socken is the world's largest Viking silver treasure]. www.lansmuseetgotland.se (in Swedish). Gotland Museum. Archived from the original on 9 May 2010. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ TT (21 December 2002). "Hittade vikingaskatt – får 2,1 miljoner i hittelön" [Found Viking treasure – gets 2.1 million in finder's fee]. www.expressen.se (in Swedish). Expressen. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ "Skattkammaren" [The Treasury]. www.gotlandsmuseum.se. Gotland Museum. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Thomsson, Lena (9 February 2010). "Gotland & Spillingsskatten – obegripligt negligerade" [Gotland & The Spilling Hoard – inexplicably neglected]. www.gd.se (in Swedish). Gefle Dagblad. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ Pettersson 2009, p. 24.

- ^ "Unikt mynt hittat i Spillingsskatten" [Unique coin found in the Spillings Hoard]. Hällekis Kuriren. 29 June 2002. Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- ^ Pettersson 2009, p. 26.

- ^ Fadlan, Ibn (2012). Ibn Fadlan and the Land of Darkness: Arab Travellers in the Far North. London: Penguin. pp. Appendix 1. ISBN 978-0-14-197504-7. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ Waugh, Daniel C. "The Silk Road" (PDF). www.silkroadfoundation.org. The Silkroad Foundation. p. 168. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ Pettersson 2009, pp. 28–31.

- ^ Pettersson 2009, p. 22.

- ^ Pettersson 2009, p. 29.

- ^ Brook, Kevin Alan (2006). The Jews of Khazaria (2 ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 80. ISBN 1-4422-0302-1. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ Pettersson 2009, pp. 31–34.

Bibliography

- Pettersson, Ann-Marie, ed. (2009). The Spillings Hoard: Gotland´s Role in Viking Age World Trade. Visby: Fornsalens Förlag. ISBN 9789188036711.